Nokia HERE Research: We talk Smart Cities, ethical tracking & self-driving cars

If you're carrying a smartphone or driving a modern car, you're a potential probe, and Nokia would love to unlock your location for its HERE Maps services. The company already has its own gathering programs in place yet, for all its gigabytes of daily data, Nokia's HERE 3D mapping car is only one part of a navigation data analysis program that combines 80,000 sources from across the globe. We sat down with Jane MacFarlane, head of HERE Research at Nokia, and along with her team responsible for making sense of the masses of data, to find out why being a probe might one day help you avoid traffic jams, travel more safely, and even discover the hottest new restaurants, all thanks to the "wisdom of crowds".

A probe, MacFarlane explains, is any source of data that Nokia can use to shape its understanding of the physical world. The Nokia exec cut her teeth in location-based services helping launch OnStar, back in the days when trusting your navigation to a smartphone was far-fetched; now, she leads a group that pulls together pings from smartphones, PNDs, fleets of delivery vehicles, and more.

In fact, there are 21 billion points of data coming in from the HERE Traffic group alone, though the sort of data MacFarlane's team has to work with is, thanks to anonymity processes, very much on the raw side. At most, she can expect a unique device ID, then latitude, longitude, speed, and heading.

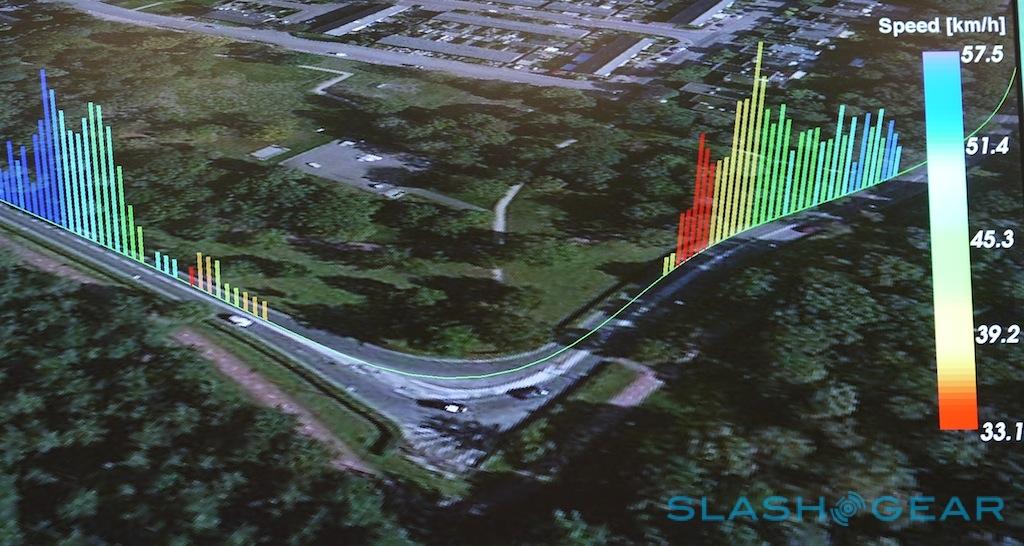

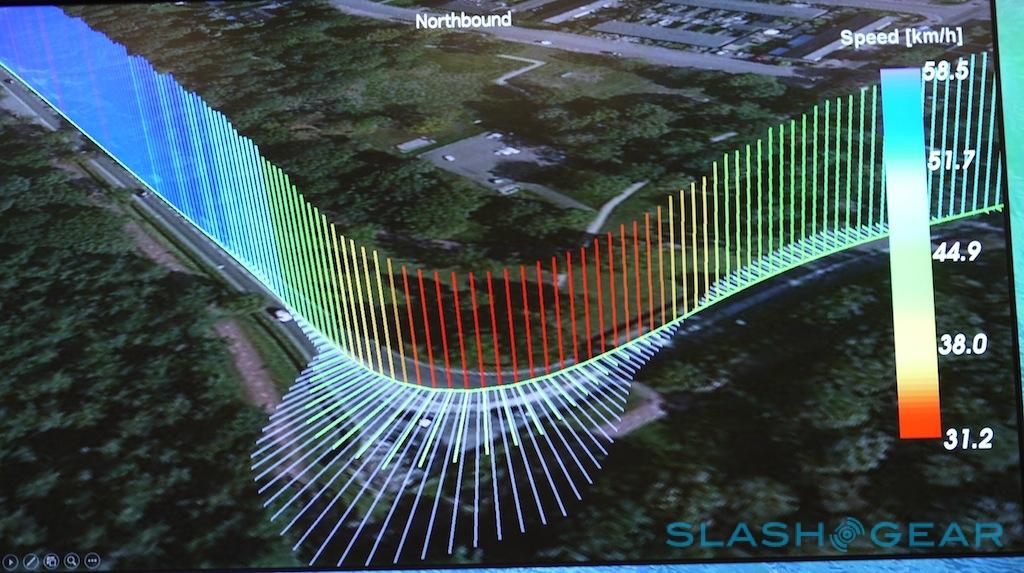

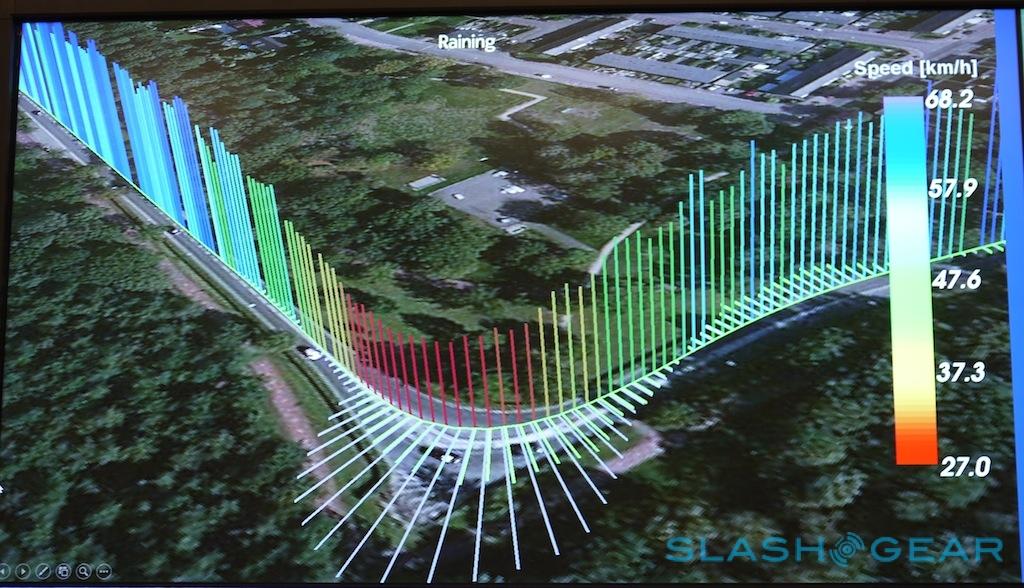

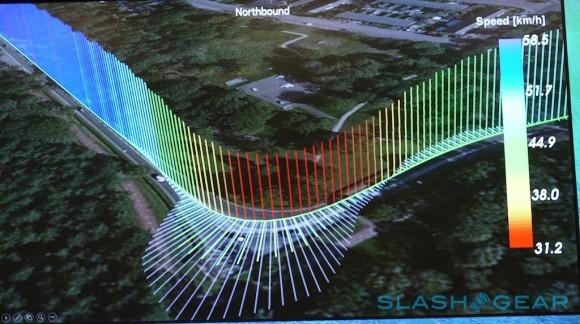

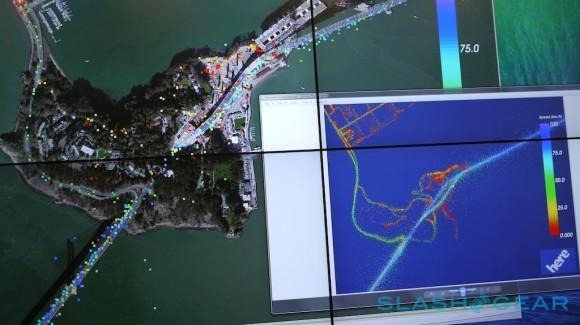

To harness that information into something meaningful, the HERE Research team developed its own visualization package, complete with a wall-sized display on which to watch it. Speed of each probe is color-coded, overlaid onto different types of map or satellite imagery. The software can only take the analysis so far, though, and MacFarlane says the group has yet to come up with a system for spotting patterns as effective as getting three or four people into the room and staring at the display.

Once the first hints of a pattern are spotted, the challenge becomes teasing that out and, then, deriving useful conclusions from it. One example – which should be visible to Nokia HERE Maps users over the coming months – is using probe data to finesse curved roads. That's something you struggle to do from pure GPS information, MacFarlane explained, because it's simply too scattershot to derive the actual topography of the road from. Look instead at data from the movement of vehicles (or the people inside them, and their mobile devices) and you get a far more accurate, far less lossy view of the infrastructure.

That precision opens up other possibilities. MacFarlane described how the HERE team used probe information to quantify the improvement of traffic flow – and thus help justify the huge investment made – when San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge switched from traditional toll-booths to an electronic system that scans license plates of moving vehicles and issues invoices through the mail. On March 26, the day before the system came into operation, long tailbacks of red "slow moving" dots could clearly be seen on the visualization; on March 27, with the toll lanes permanently open, it was clear green running all the way.

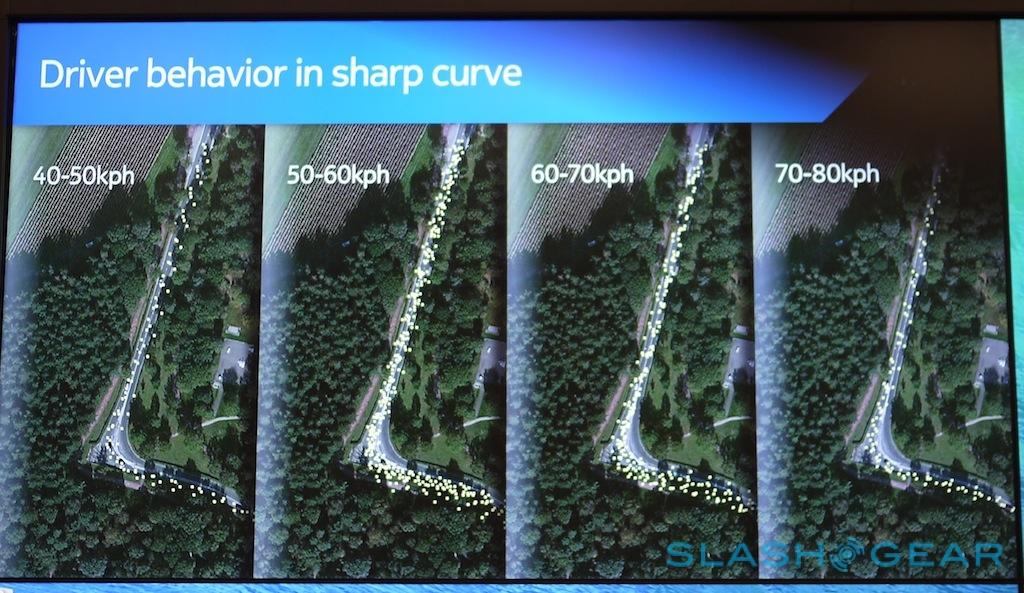

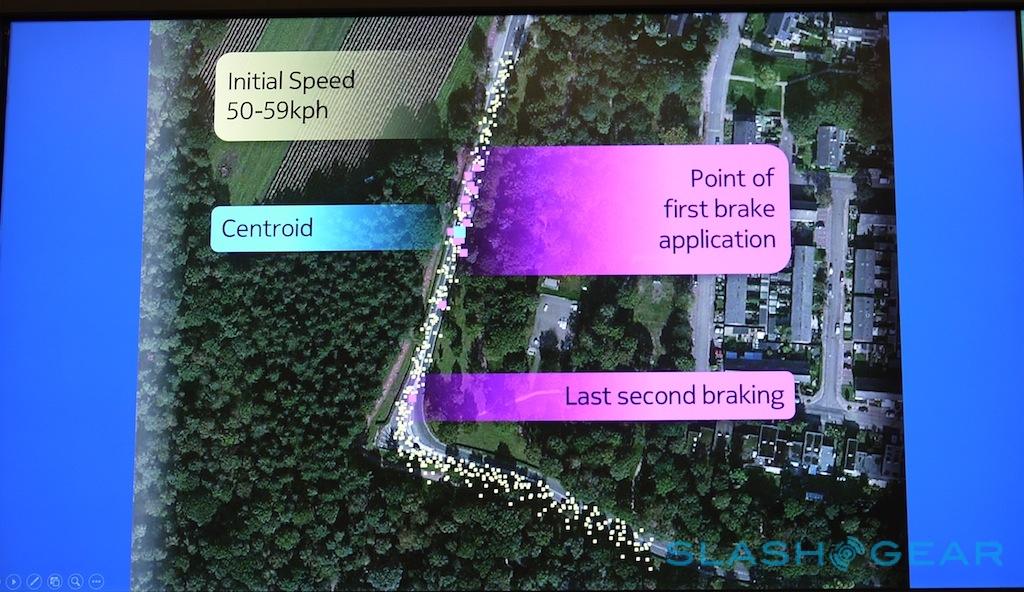

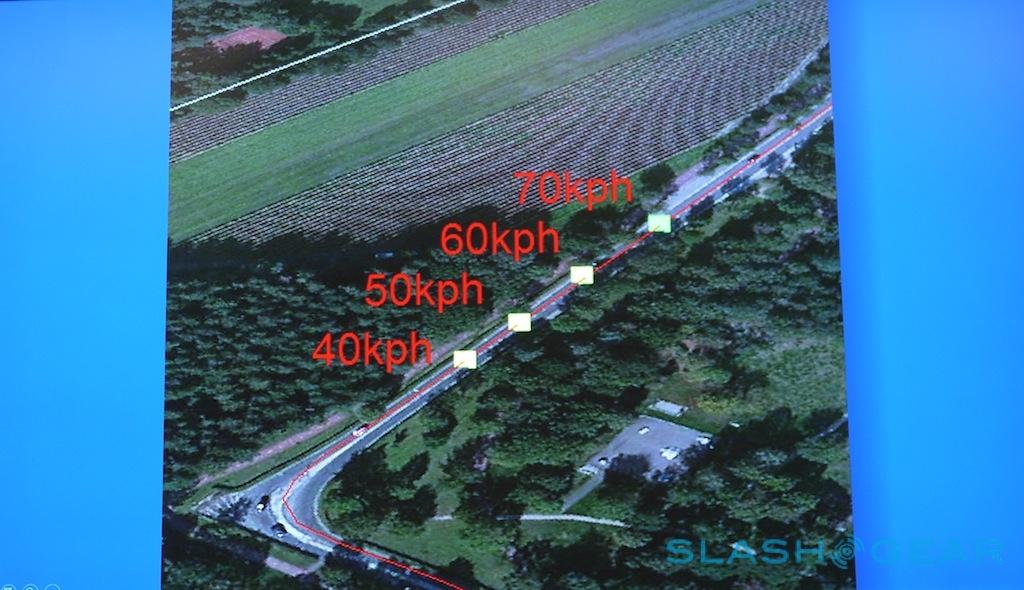

Other analysis allows Nokia to tease out information road planners and city administrators have never had access to before. For instance, by looking at an amalgamation of probe data, you can learn from the "wisdom of crowds" as MacFarlane describes it. For instance, crunching data from a particularly sharp bend in a city in the Netherlands, the team was able to see where drivers began to brake in order to take the corner.

That understanding of common behaviors helps not only with the placement of safety signs and other traffic-calming measures, if required, but educates the road planners themselves for future infrastructure development. By factoring in weather information, MacFarlane's team could show how much more dangerous the curve could be in adverse conditions such as heavy rain.

It's that ability to derive safety guidance from crowdsourced driving data that Nokia believes will shape the coming smart cities. On a relatively low-tech level, that could mean picking the right place for a warning sign, but the future is Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) for both humans and AIs behind the wheel.

For instance, MacFarlane suggested, the "wisdom of the crowd" could help educate an autonomous car on how a human pilot might safely take a sharp corner. That would make for a more familiar, comfortable experience for any passengers, but also be more predictable for any human drivers sharing the road.

Autonomous cars are still some way off – if Nokia is working on them, MacFarlane laughed, she's not privy to it – but feeding dynamic safety advice to our smartphones and dashboards is much closer. By tracking someone's usual route to work, and the speed they would normally drive at, for instance, and then factoring in known deviations from the typical patterns known for that route, a personalized warning could be flashed up if there was an unexpected hazard up ahead.

Such a hazard could be traffic, or inclement weather, or it might just be a change in the familiar road. Here, MacFarlane again used a San Francisco bridge as an example, in this case the ongoing works on the Bay Bridge that has seen engineers slot in an "S-bend" curved section of temporary roadway to clear space for the final section. By working with Nokia's team, the bridge authorities could track the different ways that drivers took the old and new roads, and thus spot that the speed limit would need to be lowered since the unexpected layout proved more distracting than anticipated.

Not all data is created equal, however, and over time the HERE Research team spotted that there was more to slow-downs in cities than just traffic. While some reduced speeds were simply a case of places where the network had become overloaded, MacFarlane and her group realized that others were what they dubbed "activity spots." Shown as orange blocks that occasionally flourish on the map, the spots are differentiated by "the signature of the probe data" the analyst explains, it means Nokia can tell between jams and when someone might be stopping for coffee or a meal.

That data is rich enough that MacFarlane can predict which are the up-and-coming places before they become ostensibly fashionable, and that information can go into better shaping Nokia's points-of-interest (POI). The HERE team is keen to see smartphones get better at understanding context – something we've come to refer to as the "context ecosystem" – and that means taking what the system knows about a user's individual preferences, routines, and habits are, and making timely and accurate suggestions.

The value of those suggestions will increase, MacFarlane points out, as the amount of data Nokia has to work with. So far, the aggregated, anonymized probe results are numerous but relatively shallow; what the HERE Research team is really interested in is unlocking the information contained in a car's onboard computers.

Those computers are already gathering up a huge quantity of information about the state of the car – everything from which lights are on, gear-change patterns, whether there's a passenger in the front seat, and what the current mileage is – which, when factored into Nokia's geographical data, opens the door to even deeper analysis. For instance, in the graphic below, Nokia tracked the movement of a rainstorm around a city by crunching the windshield wiper activity of 80 different taxis. Since the car is not only recording whether the wipers are on, but at what speed they're active – in addition to how fast drivers are moving, braking times, and other road information – the HERE team could then calculate likely weather conditions and issue warnings if necessary.

To do that, though, Nokia needs access to the CAN Bus, the centralized hub for data in each modern vehicle, and that's something car manufacturers themselves jealously guard. There are also ongoing alternative approaches that the manufacturers themselves are pushing, such as Mercedes Benz's Car-to-X system, set to start vehicles talking between themselves later in the year. MacFarlane – given her history in in-car tech – is intrigued by so-called Car-2-Car systems, but pointed out that they're very different from "Car-2-Cloud" and, right now, there's no one single standard for intercommunication that's been agreed upon by all OEMs and in all countries.

There's another, broader problem than that, however; namely, filtering the massive quantities of information into something that can be worked with in a meaningful way. One part of the HERE Research team's current work is creating better algorithms for actually processing the collated data, trying even in a basic way to replicate the pattern-identification that, so far, humans have proved best at. The tools are already improving, MacFarlane told us, but it's still relatively early days, and while Nokia can crunch through 21bn points of traffic information in minutes, generating something meaningful on the "wisdom of crowds" scale takes more time.

The flip side of the data overload issue is how – and when – to deliver information back to the user. So far, the HERE app has been shy of pushing too much back to devices, but that's only going to become more topical as increasingly granular analysis becomes possible. Some of the questions MacFarlane's team are looking at are whether the initial processing should take place locally, on phones and in cars, or when it has reached the cloud servers, and how that might affect data networks, along with how this richer understanding of the environment will work with the evolving Human Machine Interface (HMI) in the dashboard and on our mobile devices.

What the HERE team doesn't want to do, MacFarlane points out, is throw so much at drivers and pedestrians that they end up ignoring the information by default, or even worse that it might become a hazard in and of itself. There's the potential, for instance, to reach drivers who don't bother reading the instruction manual and thus don't know that their cars can flag up route delays, warnings, and such, but only if the impromptu alerts themselves are accurate and precisely targeted enough to make them welcome rather than distracting.

Even then, there's no guarantee that drivers will actually follow the advice the HERE team generates, and so, MacFarlane says, there needs to be companion research into how they can incentivize changing route or driving time to miss hotspots of congestion. Still, she believes, if Nokia can demonstrate over time that there are real benefits from its HERE suggestions, that will help convince users to actually pay attention.

The result may be a shift not toward autonomous driving – still some way off – but assisted driving, where the car can call upon localized expertise and, perhaps even invisibly, shape the suggestions it makes in terms of route and POIs based on the sort of experience-led understanding that a true local might possess.

Not all maps are created equal. That, Nokia says, was the realization many users came to last year, when Apple Maps had its launch stumble. Rather than being a binary question of "do you have a map app?", the focus shifted to the quality of the data being used; since then, we've seen Apple work steadily to improve its offering, but face significant challenges from Google Maps, most recently including its own "wisdom of crowds" style intelligence with Waze traffic alerts.

For Nokia HERE Maps – and other products that Nokia supplies the data for, many of which aren't branded with the Finnish company's name – the next thing users themselves should start noticing is better POI suggestion and discovery. As Apple highlighted as it made its Maps reparations, since so much of the overall experience is driven by what's happening server-side, it's possible to invisibly improve apps rather than push out local update after update.

Location-based services are tipped to become the next big thing in mobile. Understanding how people travel, what they pay attention to when they do, and where they choose to spend their time and money are potentially valuable metrics to advertisers, vendors, and more. Then there are the safety advantages of being better-educated, more efficient drivers. Before that can happen, though, teams like Nokia HERE Research need to develop ways to collect, process, and package it so that it's meaningful rather than overwhelming. "All that data is there," MacFarlane reminded us, "it's just really big."