Map Democracy: Telenav bets on the crowd crushing Google

There's more than one way to get where you're going, and there's more than one app to navigate it, and if Telenav and OpenStreetMap have their way it'll be the power of the crowd not locked-up, heavily licensed data powering it all. SlashGear caught up with Steve Coast, founder of OpenStreetMap and currently OSM lead at Telenav, to find out what's next for the team aiming to put Google Maps and Nokia HERE on notice, and democratize mapping in the process.

"You can always map more," Coast says of the evolution every mapping provider faces, when we talked to him at Telenav's annual Waypoint conference. "You could map every single tree, if that's interesting to you. But the other thing is change detection – when the road is closed, for instance. When those things happen, you need people out there fixing the maps. On most maps those things don't change, because there aren't people out there changing them."

It's here that by owning the data, OpenStreetMap can differentiate itself from other companies. When events close off roads or other areas, OSM's editors can in effect make live changes and modify the core map, sharing updates that every app, service, and site using those maps will get instantly.

In contrast, licensing limits on data from mainstream providers means that the core maps themselves can't be changed. Instead, elements like traffic or road closures have to be abstracted on top in a secondary layer. It's an example of how flexible the OSM data set can be, not to mention how compact it can be kept: figure on around 8GB for mapping for the entire globe.

OSM actually relies on two types of feedback from its users. The most obvious is active mapping: additions and edits of new roads, buildings, and more. However, there's also the background changes that are enabled every time apps like Scout are run. Users are "passive editors of the map with every drive they make," Telenav head of product Rohan Chadran explains, each acting as a data-gathering probe.

That probe data also allows OpenStreetMap to better utilize what resources it does have, despite them being a fraction of those the big commercial mapping firms wield. OSM has done more than 10,000 miles of physical test drives in the US alone, checking roads for their accuracy, but that's still a drop in the ocean compared to the full network.

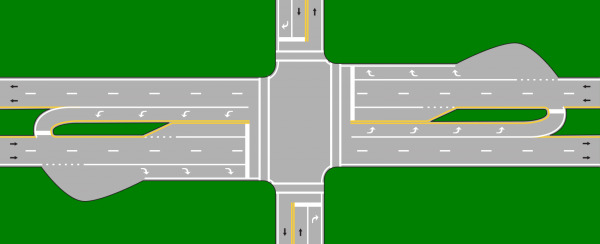

Using probe data – automatically and anonymously fed back from products like Telenav Scout which as of this week will use OSM data – can give a heads-up on where attention actually needs to be paid. Different US states, for instance, can have their own, unusual junction styles, such as the so-called "Michigan Left". There, Coast explained, rather than allowing drivers to turn left at an intersection, they have to pass through it and then make a U-turn shortly after, doubling back and then making a right turn.

Wikipedia has an entry for the Michigan Left, Coast pointed out, but not a definitive list of all of the junctions to feature it. Probe data can help identify them, however, based on frequent maneuvers fed back by GPS data. That can compile an automatic shortlist of possible intersections, which can then be validated either by physically visiting or by checking satellite photography.

It may not be enough for the cartography required in tomorrow's world; mapping needs to grow up. Roads and bicycle paths are no longer sufficient, particularly as applications like autonomous vehicles arrive demanding higher and higher resolution data. Projects like Google's fleet of self-driving cars may be bristling with sensors and lasers, but they still need better-than-average maps to be able to correctly place themselves.

Such efforts are already underway by the big, private mapping companies – Nokia's HERE division has dubbed its handiwork Map HD, for instance – to factor in details like individual lanes, road elevation, and more, which a human driver might take for granted but a robot car would need to be told. It also raises the question of whether OpenStreetMap and its army of users can hope to deliver the same resolution of data.

When I challenged Coast on whether OSM was in a position to compete on those terms, he was adamant that not only was it possible, but that he felt it was the only real approach that would work.

"I think only OSM can do it," he argued. "[Commercial providers] can't even get the existing maps right. You need to have some sort of crowdsourcing."

One thing seems clear, if OpenStreetMap can provide users with the necessary tools, it can count on them to go out and use them. The first OSM mapping party took place on the Isle of Wight in 2006, a team effectively plotting the whole 148 square mile island in the space of a weekend; now, mapping parties take place every month in countries around the world. There's a hardcore cadre who will go to extreme lengths to make OSM the most accurate navigation platform out there, even if it puts them in potentially dangerous situations.

"We've had people arrested doing this for OpenStreetMap," Coast says, somewhat sheepishly. "People have been arrested for walking down the middle of the road, with GPS devices, at four o'clock in the morning."

Inside the team tracking America's roads

Next up, therefore, is delivering those better tools. OSM already has a solid selection of desktop editing apps, but the mobile equivalents have lagged behind. That means changes often have to wait until users are back home – assuming they remember the full details.

Another is addressing a perception issue: crowdsourced traffic app Waze, which Google acquired in 2013, makes it very clear what value its contributing users are making from the map itself, Telenav CEO HP Jin points out. Scout does a very similar thing using its own probe data, Jin says – arguing that Telenav's traffic data fed in from iPhone users of the app is as good as, or even better than, what Waze offers – but doesn't surface that information in such an engaging way.

OpenStreetMap and Scout are two separate projects, of course, even with Coast now part of the Telenav team. Yet, by tying its mapping fortunes solely to OSM, Telenav is taking a considerable bet on the potential of the crowd – not to mention committing to giving users the most compelling motivation to both consume and engage with their map platform.

Building on that, there's the new Telenav SDK, offering exactly the same tools and technologies to third-party developers that the company itself has. In fact, external developers will in some cases be launching new features based on the SDK which Telenav itself hasn't had time to add to Scout.

For instance, RealReach will use OSM and Telenav's minute-by-minute updates to show exactly where a driver could go within a set period of time, taking into account things like road type and traffic. However, that can be bolstered with extra data to suit specific users: those behind the wheel of an EV, for instance, could see which public charging stations are within their remaining range.

There's also a 3D elevation model in the SDK, another thing Telenav itself is yet to implement in Scout, which could be used to figure out more efficient routes for all-electric or hybrid vehicles.

Telenav is counting on pricing coming in at around half what Google and others are charging – plus an entry-level tier with a sufficiently high free threshold to allow startups to experiment without running up high fees – to drive adoption, in turn increasing the number of individual users feeding data back into the system.

"High quality, high price map data sets have to do something," Coast concludes. "They either have to come down in price, or in quality, or they have to go out and innovate, do something new."

Telenav Scout for iPhone gets the OpenStreetMap update this week

Michigan Left image via Wikipedia