Scientists Develop A Smartphone Camera To Illuminate Skin Bacteria

University of Washington researchers have developed a new method of using images from a smartphone to identify potentially harmful bacteria on human skin and in the mouth. Their new approach was outlined in a paper published recently and can visually identify microbes and skin that contribute to acne and slow wound healing. The same system can identify bacteria in the oral cavity that can lead to gingivitis and dental plaque.The team from the University of Washington was led by Professor of bioengineering and ophthalmology, Ruikand Wang. The team combined a smartphone case modification with image-processing methods to eliminate bacteria on images taken by a conventional smartphone camera.

Researchers say the approach yielded a relatively low-cost and quick method that could be used at home to assess if potentially harmful bacteria are present on the skin and in the oral cavity. Wang says the bacteria on the skin and in the mouth can cause tooth decay and slow down wound healing. With the wide prevalence of smartphones, the team wanted to develop a cost-effective and easy-to-use tool that people can use to learn about bacteria on the skin and in the mouth.

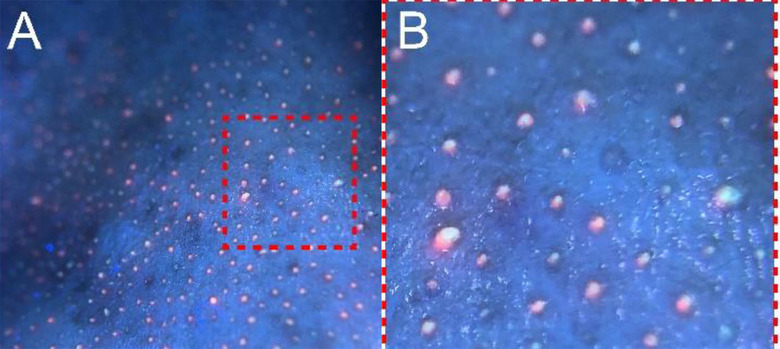

Typically, bacteria aren't easy to see using conventional smartphone images. Wang says that conventional smartphone cameras are RGB units that funnel different wavelengths of light in the visual spectrum into three colors of red, green, and blue. Bacteria emit colors beyond red, green, and blue, and the typical smartphone camera misses those colors. Researchers augmented the smartphone camera capabilities by attaching a 3D-printed ring that contained 10 LED black lights around the smartphone case's camera opening.

The LED lights excite the class of bacteria-derived molecules called porphyrins that cause them to emit red fluorescent signals the smartphone camera can pick up. Other components in the image, including proteins, oily molecules produced by the body, skin, teeth, and gums, don't show under the LED. Wang says they'll fluoresce in other colors. Wang says the beauty of the technique his team developed is that they can look at different components simultaneously. If the user has bacteria producing a different byproduct, you want to detect that, and you can use the same image to look for it using the team's approach, which is something impossible with conventional imaging systems today.