New Transparent Electrode Using Ultrathin Gold Film Improves Solar Panels

Researchers from Penn State University have created a new ultrathin metal electrode enabling the creation of semitransparent perovskite solar cells that are highly efficient. The new solar cells can be coupled with traditional silicon cells to boost the performance of both devices significantly. Scientists on the project say their research is a step towards developing completely transparent solar cells.

Completely transparent solar cells could be a game-changing advance in green energy with the ability someday to replace traditional windows in homes and office buildings to generate electricity from sunlight. While traditional solar cells are made from silicon, scientists believe they are approaching the limits of the technology and the ability to make them more efficient. Perovskite cells offer a compelling alternative to the traditional production methods, and by stacking perovskite cells on top of traditional cells, scientists create a more efficient tandem device.

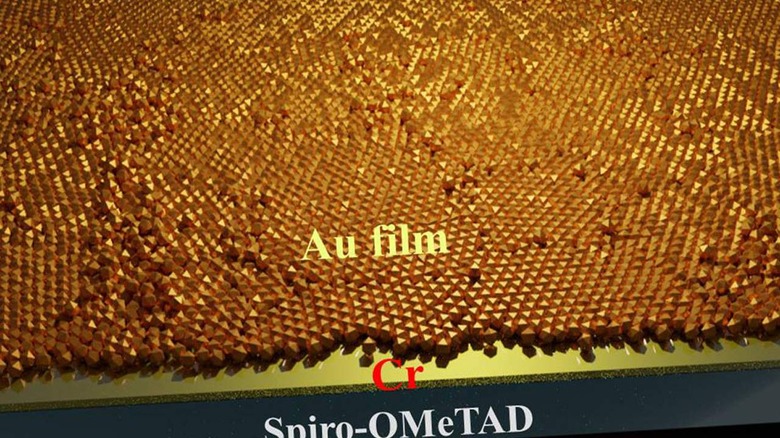

Researchers were able to make electrodes that they describe as almost a few atomic layers of gold. The thin gold layer has high electrical conductivity while not interfering with the cells ability to absorb sunlight. The perovskite cell the team developed has a 19.8 percent efficiency, a record for a semitransparent cell. When it was combined with a traditional silicon solar cell, the tandem device achieved 28.3 percent efficiency, which is a gain from the 23.3 percent efficiency of the silicon cell alone.

While a five percent improvement might not sound like much, researchers say a five percent improvement in efficiency is giant. That means you're converting about 50 watts more sunlight for every square meter of solar cell material. Solar farms can consist of thousands of modules, and five percent adds up to a significant amount of electricity.

The new research improved past research in the ultrathin gold film where the film showed promise, but issues creating a uniform layer resulted in poor conductivity. The team got around that problem by using chromium as a seed layer to allow gold form on top in a continuous ultrathin layer with ideal conductive properties.