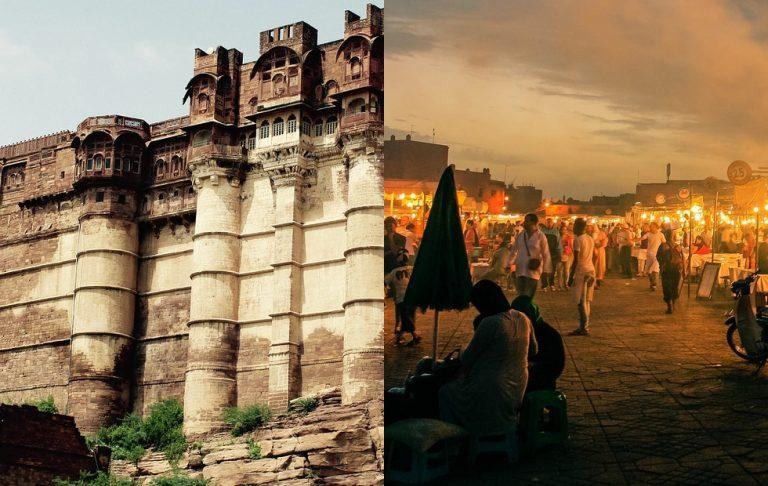

iTunes App Store versus Google Play Store: fortress or bazaar

There's no arguing that Facebook made a massive blunder in the way it handled the Cambridge Analytica situation. It has caused many big names in many industries, ranging from tech to advertising, to pull out their support or chide the social networking giant. Apple, who has been painted as the poster boy for protecting customer privacy, naturally criticized Facebook's behavior. But in explaining how Apple would have done it differently, Tim Cook pit the company's practices and philosophy against those of more "open" app and content markets, like Android's Google Play Store. But which strategy is the right one to take, especially in this day of rampant privacy violations? As you might expect, the answer isn't clear-cut.

A meticulously manicured jail

It's not hard to see Apple's logic. And in light of recent events, it's even easier to sympathize with its philosophy. Almost half of Apple's success comes not just from its products but from its brand and reputation. Many people buy Apple products because they're Apple products, whether or not there's something better that's not made by Apple. As such, the company needs to protect its name from anything that would tarnish it. Of course, in practice, that means carefully trying to protect users, sometimes even from themselves.

So despite the inhumane amount of apps out in the world and despite being the bottleneck in the process, Apple continues to screen anything and everything that goes into its store. Many hail this as the reason there is almost no malware on the iTunes App Store. Of course, some still do slip through the cracks, be it malware or cryptominer, but it's admittedly fewer than the competition.

But Apple's ecosystem isn't just curated. It is also completely proprietary. Yes, Apple does have public guidelines, but they are completely opaque to everyone but Apple. Apple can pull those from under people's rugs at any time, with little to no warning and sometimes for no immediately obvious reason other than it can and wants to. And developers, and the users who may have relied on those apps, will have no other choice than to accept their fate.

And there's the fact that Apple is a for-profit, publicly traded company. One that has many rivals in many spaces. It will always make decisions that will benefit the company. Benefiting its customers is, of course, the means to that end. But when a choice has to be made between making it easier for iOS users to buy eBooks or ensuring no other app or content store will compete with Apple on its own platform, you can pretty much be sure which path Apple will take.

The Wild Wide Westworld

The app and content store outside of Apple is less defined. Some would even call it a mess. A beautiful mess, perhaps, but still a mess. Android is just the biggest example but, as Facebook painfully made everyone more aware, there are others as well. Android is also the most open of them, and a perfect target for Cook's criticism.

In complete contrast to Apple, Google lets almost everyone into its Play Store. Geeks at heart, it prefers to use automation, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to sift through apps and submissions. It's an efficient method considering the thousands of apps that go through the Play Store. But it's not a completely effective one, judging by month after month of malware reports. It might get over time, which is pretty much the promise of machine learning. But, as it stands, it's far from being ideal.

And that's just the apps that do agree to play by Google's rules in exchange for a slot on the Play Store. Just like Apple, Google has its own rules and guidelines and, just like Apple, it sometimes uses those for its benefit more than its partners or customers. But unlike Apple, Android users can have recourse to other sources of apps and content, and not all of those can be trusted in equal measure.

Openness isn’t anarchy

Cook isn't entirely wrong in painting the "other ecosystem" as a sort of lawless land. There are laws, mind, but there are also ways to get around those.

Google's machine learning methods aren't exactly working. It may need more time to learn, time that users might not have or can afford to risk. At the same time, Apple's system might not scale in the future where an even bigger explosion of apps and services happen. Its uneasy peace with developers and users might not last forever either.

It's almost ironic that Google isn't utilizing a model it should already be very familiar with: open source software development. In open source, there is no one single authority and no one single bottleneck. There may be, but even Linus delegates Linux tasks to his generals. Instead, there are trusted circles keep eyes on what goes into the codebase. It's pretty much a shared responsibility.

Of course, it's not going to translate perfectly into most app stores, especially closed ones. Still, it's a model than can be adapted to great effect. Wikipedia might not be the best example, but it has proven how crowdsourcing can be a powerful tool when used properly. It can keep the ecosystem open but still have enough eyes available to check that everything is in working order.

Wrap-up

Apple is hardly going to change its ways, especially after incidents like this seem to verify its strategy. Google is still keeping its doors open, relying on AI and machine learning to patrol its stores, but is also tightening the noose in other aspects. Both represent extremes in philosophy and implementation, and extremes don't exactly work well over time. As privacy and security issues become worse and more common, some things have to change, hopefully, sooner rather than later.