Caltech Researchers Develop A New At-Home Multiplexed Test For COVID-19

One of the challenges of detecting COVID-19 is tests that are accurate and easy to use. Researchers from Caltech have developed a new kind of multiplexed test, which is a test that combines multiple kinds of data with a sensor that is low cost and could enable at-home diagnosis of COVID-19 infection. The test is designed to rapidly analyze small volumes of saliva or blood without needing a medical professional in under 10 minutes.

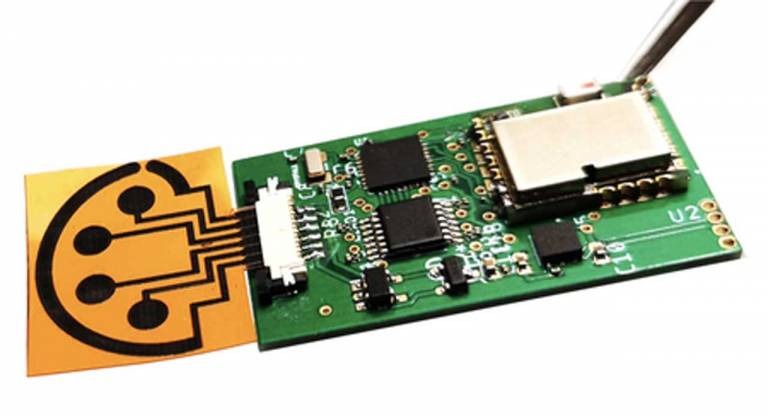

The research team that invented the test is from the Caltech lab of Wei Gao, an assistant professor in the Department of medical engineering. Previously Gao and his team developed wireless sensors to monitor various conditions, including gout and stress levels, by detecting extremely low levels of specific compounds in blood, saliva, or sweat. The sensors the team developed use graphene, which is a form of carbon.

The sensors use a plastic sheet etched with a laser that generates a 3D graphene structure with tiny pores creating a large surface area on the sensor. The large surface area makes the sensor sensitive enough to detect compounds present in minimal amounts of blood or saliva with high accuracy. Graphene structures on the sensor are coupled with antibodies sensitive to specific proteins, such as those on the surface of the COVID-19 virus.

Gao calls the sensor the SARS-CoV-2 RapidPlex. It contains antibodies and proteins that allow the detection of the virus itself, antibodies the body makes to fight the virus, and chemical markers of inflammation that indicate the infection's severity. Gao says that the sensor his team has developed is the only telemedicine platform he's aware of that gives information on the infection in three types of data with a single sensor.

The researchers have used the device in the lab only so far with a small amount of blood and saliva samples obtained for medical research purposes from individuals who have tested positive or negative for the virus. The preliminary research indicates the sensor is highly accurate, but researchers warn that testing with real-world patients is needed to determine the sensor's accuracy.