A small meteorite discovered in Antarctica is incredibly well preserved

In 2012 a group of Japanese and Belgian scientists was on an expedition in Antarctica. The team discovered something surprising lying on the snow covering the continent in the form of a meteorite about the size of a golf ball. The meteorite was officially named Asuka 12236, and despite its rather small size, it turned out to be one of the best-preserved meteorites of its kind ever discovered.

At the Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA scientists were eventually able to get their hands on a small slice of the primitive meteorite processing and decoding the information inside. After processing a small portion of the meteorite in the lab with the mortar and pestle, they suspended the amino acids from the ancient dust in a water solution. They fed the liquid into a machine designed to separate molecules inside by mass and identify each kind.

The team discovered that locked inside of the meteorite was an abundance of amino acids. The meteorite had twice the concentration seen in a space rock called Paris, the previous best-preserved meteorite of the same class. The molecules included aspartic and glutamic acids, two of the 20 amino acids that form themselves into varieties of arrangements that make up proteins.

Those proteins are critical to life on earth. Researchers have found that meteorites are full of what the team calls left-handed amino acids, precursors to life, which they believe may explain why life on earth tends only to use the left-handed amino acids. When looking at the solar system timeline, Asuka 12236 fits in towards the very beginning, with some scientists thinking that meteorite may predate the solar system.

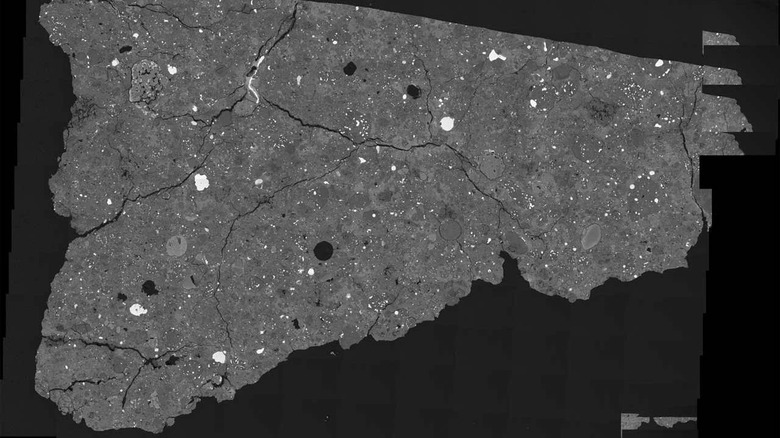

Asuka 12236 is so well preserved because it was exposed to very little water or heat when it was still part of an asteroid and later. This was determined because while the meteorite has lots of iron metal inside, that iron hasn't rusted, indicating the meteorite has been exposed to the oxygen and water. It's also filled with silicate minerals that the team believes formed in ancient stars that died before the sun began to form. Silicates are typically destroyed by water and aren't found in less well-preserved meteorites.