How The Apple Newton's Failure Led To The iPhone

Apple's approach to smartphone innovation in the past decade has focused more on refinement, instead of racing ahead of rivals. High refresh rate screens? Apple only warmed up to the idea last year. Crazy-fast charging? iPhones still have a long, long way to go. Megapixel-heavy cameras? 2022 iPhones peak at 12-megapixel, while Android phones are readying for the 200-megapixel race. But that was not always the case.

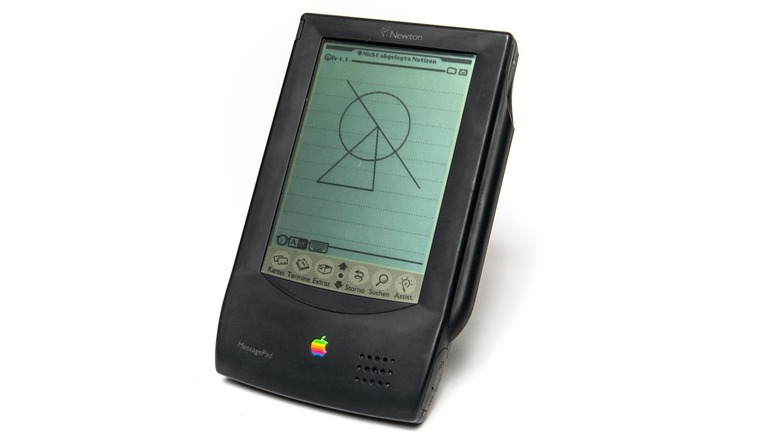

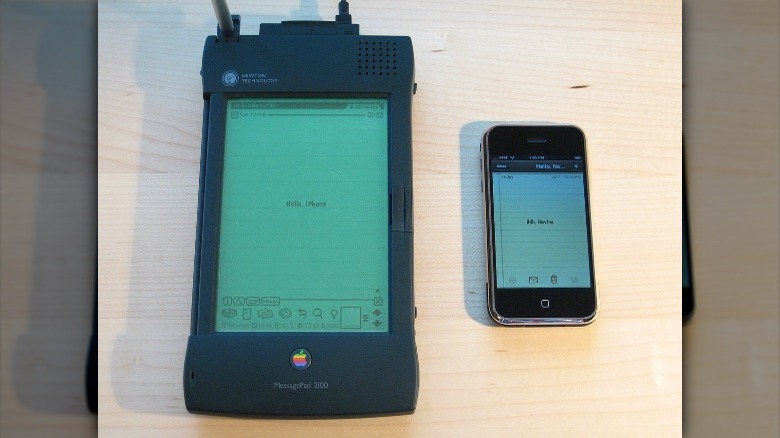

The oft-maligned Apple Newton MessagePad was an innovation ahead of its time when it first arrived in 1993. It was deemed a colossal failure, but part of it lives on in the iPhone. And to some extent, in the world's favorite tablet — the iPad. The Newton MessagePad catalyzed a new category of computers called PDAs, short for Personal Digital Assistants. What it promised was revolutionary, but what it delivered was a potpourri of half-baked features and misfiring tech. And yet, its influence on the iPhone is undeniable.

It's worth starting with the form factor. When Apple chief John Sculley was first pitched the idea of a handheld computing device, he wanted it to be small enough for the pocket and could be held comfortably in one hand, per a WIRED report. When Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone over a decade later, it was seen as more than just a phone with cool tricks up its sleeve. It was a pocketable computer, in all essence. Walt Mossberg wrote for The Wall Street Journal that the iPhone was "a beautiful and breakthrough handheld computer."

Dawn of pocket computing with touchscreens at helm

But raving about the form factor similarities is tantamount to merely scratching the evolutionary surface here. One feature, in particular, that received the most attention — both, good and bad kind — was the handwriting recognition for text-based user input. Touch-based input for computers was somewhat of an alien concept back then. And yet, Apple embraced it fully for the Newton over the bread-and-butter keyboard input. For some, it was ahead of its time and a peek into the future of pocket computers. For others, it was a gimmick, especially when Newton's recognition system erred. It was mocked viciously, both in print and media.

But unlike the Touch Bar on MacBook Pro, Apple didn't shelve the idea. In the years leading up to the Newton line's discontinuation in 1998, Apple actually improved on it with each iteration. But the problem was two-fold here. The first Newton MessagePad shipped with 10,000 words pre-installed for recognizing whatever users scribbled on its monochrome screen. For folks imagining a notepad jotting session in any script other than English, the Apple device was a $699 piece of disappointment. Another aspect that was out of Apple's grasp was the lack of connected software infrastructure, one that could help upgrade the recognition system, and more importantly, take full advantage of its capabilities.

Newton was the progenitor of smart assistants

When the iPhone arrived, there was a whole ecosystem of websites and apps ready for touch and tap-based interactions on a fully touchscreen device. Steve Jobs reportedly loathed the first Newton, but the idea of a keyboard-less pocket computer that it pioneered was on display in full-force on the iPhone. Of course, the iPhone came in the days when the button-loving phones and communicators were all the rage, and an all-glass touchscreen slab was met with skepticism. And yet, the iPhone changed the world's smartphone game on its head in a shorter window than the Newton's entire lifespan.

Another pioneering aspect of the Newton software was what Apple called "intelligence assistance." It essentially tried to understand what users wrote on the screen and turned said writings into actionable commands. Writing a statement such as "Fax to Allen" at the end of a note would evoke a prompt for sending it to a person named Allen in the contacts directory. Scribbling "Lunch with Sophia on Sunday" pulled up the calendar and made an automatic entry after the user's consent. It was a smart assistant by definition, something that is now synonymous with Siri on the iPhone.

Where Newton relied on text-based input, Siri made the leap to voice recognition. Siri arrived as a standalone app in 2010, and was acquired by Apple that same year. And just like the Newton MessagePad, it divided opinions. Some saw it as a gamechanger, others dismissed it as just another attempt to cash in on the voice recognition trend. WIRED wrote in its iPhone 4S review that "Siri is the reason people should buy this phone." Siri improved by leaps and bounds over the years. But more than being just another virtual assistant, it is a bittersweet homage to Newton's "smart intelligence" system whose true potential was only realized over a decade later.

A failure that evolved into a landmark

Newton's primitive (by today's standards) software was bogged down by the lack of an ecosystem around it, and yet, it followed user interface principles that can still be felt in iOS design DNA today. Jesse Freeman, a senior marketing executive at Akamai, breaks it down beautifully in a UXDesign article. When the iPhone arrived, it was driven by apps and a internet-connected software that was ready to take advantage of all the smarts and processing power it had to offer.

The Newton, in all its iterations, was a business and PR failure for Apple, much like the original Apple video game console Pippin. Such was the sting that one of Steve Jobs' first acts after returning to Apple's helms was killing the product. But as Mashable puts it, the Newton MessagePad was a beautiful failure. The Apple PDA was dragged down by a weak processor, bad display, and sub-par software experiences. But the lessons lived on. When the iPhone arrived, the software stage was set. The technology was ready. And all of Newton's unfulfilled promises were realized to a raucous success that helped Apple become the trillion-dollar behemoth it is today.