3D Images Of Shark Intestines Reveal How They Function

Sharks are some of the most iconic predators of the ocean. Despite what we see in movies and on TV, scientists don't know much about what sharks eat in the wild. Even less is known about how sharks digest food and the role the shark plays in the ocean ecosystem. Scientists have relied on flat sketches of the digestive system of sharks for centuries to learn how they function, what they eat, and how they excrete.

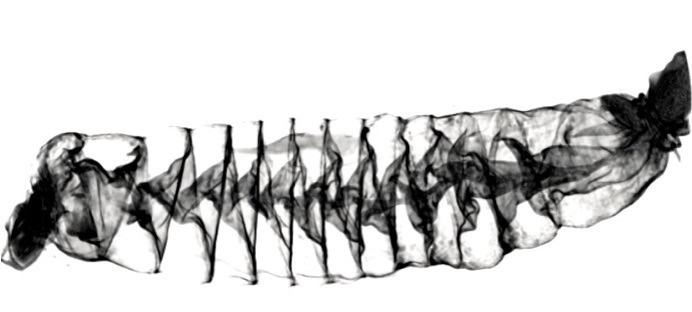

Researchers have recently produced a series of high-resolution 3D scans of intestines from nearly three dozen shark species. They say it will advance the understanding of how sharks eat and digest food. Study lead author Samantha Leigh says that it was time modern technology was used to look at the spiral intestines of sharks.

Leigh says the team developed a new method to digitally scan the tissues and look at the soft tissues in great detail without having to slice into them. Primarily, the team used computerized tomography (CT) scanner at the Friday Harbor Laboratory to create 3D images of the intestines from specimens preserved at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. The scanning method allows the researchers to see the complex nature of the shark intestines without having to dissect the specimens.

Study co-author Adam Summers says that a CT scan is one of the only ways to understand the shape of a shark's intestines in three dimensions. The scans revealed several new aspects of how the intestinal system functions. It appears the spiral-shaped organ slows the movement of food and directs it downward to the gut relying on gravity and the rhythmic contraction of smooth muscle in the gut.

Researchers say the function of the shark intestines resembling one-way valve designed by Nikola Tesla more than a century ago. That valve allows fluid to flow in one direction without backflow or assistance for moving parts. The team says the findings could shed light on how sharks eat and process their food. The team notes that the vast majority of shark species and the majority of their physiology is completely unknown.