Will Hydrogen Powered Cars Ever Surpass Battery-Electric Vehicles, Or Are They Doomed To Fail?

The race between Hydrogen fuel cells — and hydrogen-powered engines — and battery-powered electric vehicles (BEVs) used to be as neck-and-neck as HD-DVDs and Blu-ray discs. While hydrogen power hasn't dissolved like the ill-fated media format, it has taken a backseat as BEVs and hybrid vehicles eat up most of the spotlight.

At this point, do hydrogen-based vehicle power alternatives still have a chance at a comeback? And if they do, could they leave BEVs in the dust? It seems like that scenario isn't entirely out of the question, but there are a lot of factors at play.

SlashGear spoke with Professor Laine Mears, Department Chair of Automotive Engineering at Clemson University — part of the International Center for Automotive Research (CU-ICAR) campus in Greenville, SC. We sent several questions about hydrogen- and battery-powered vehicles (past, present, and potential future), and offered his expertise.

Mears has been part of the faculty at CU-ICAR since 2006, teaching students about model analysis and multiple facets of automotive and automation manufacturing. He is researching processing control for materials that are difficult to machine, model-based control for processes and systems in manufacturing, and the development of new novel processing techniques for electrically-assisted manufacturing along with metal injection molding.

Why are hydrogen cars still a thing?

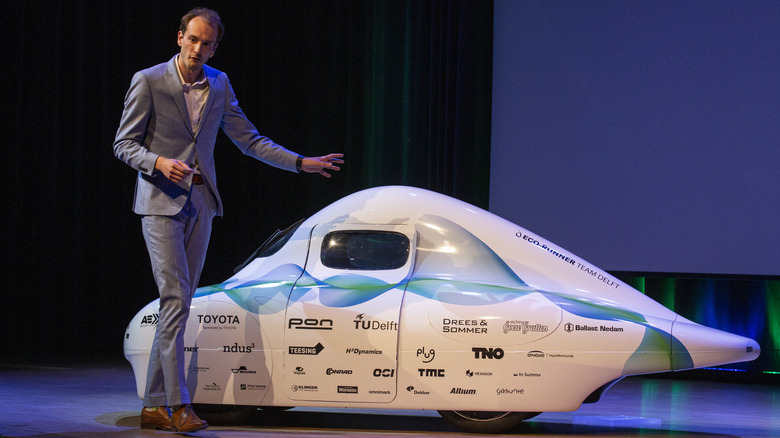

While EVs are far more prevalent, hydrogen-powered vehicles haven't stopped existing just yet. Professor Mears notes that several companies initially started working on hydrogen fuel solutions before the spike in EV (and by extension, hybrid) interest. And while most of those designs were shelved, they weren't thrown out, so it's not unreasonable to think they could be revisited.

Mears also points out that U.S. drivers being less inclined to initially spend more to save (both on fuel costs and emissions) in the long term might be putting hydrogen power back on the table, along with the manufacturing and materials costs of EVs. It's an environment that would likely benefit from having more than one alternative for fossil fuels.

"The prevailing wisdom now is that the 'green' transition will encompass a diversity of platforms as markets and consumer sentiment evolves," Mears explains, "and hydrogen-fueled cars will be part of that solution."

Are there some sectors where hydrogen vehicles are preferable over BEVs, and could they keep the tech alive?

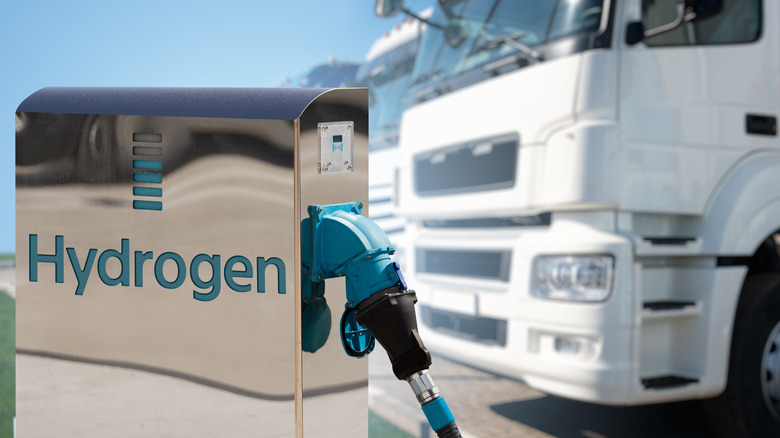

Hydrogen-based fuel alternatives could very well become as much a part of the commercial market as EVs and hybrids are. However, according to Mears, there are two main hurdles the technology needs to clear (and is already in the process of dealing with) before that can happen: Fuel availability and general safety.

"Safety is being addressed well through tank designs and redundant systems, so hydrogen vehicles should have similar crash concerns as other vehicles," notes Mears. So safety is less of an overall issue for hydrogen power, but fuel is still a bit of a sticking point due to hydrogen primarily (but not exclusively) needing to be created through other energy sources rather than mined like the core components of gasoline.

"In order for widespread adoption to work, investment in broad infrastructure would be needed, both for generation and distribution," explains Mears. "The US Department of Energy is starting to build the framework of such a solution through its Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs program, where 6–10 pilot networks will be established to create and supply hydrogen for future decarbonization."

Is there an edge over BEVs in the general automotive market?

Both batteries and hydrogen are seen as proving the benefit of cleaner energy, but the one area where Mears says BEVs are lacking is in the batteries themselves. A combination of the materials needed to manufacture them and how complicated they can be to recycle, the weight they add to a vehicle, and a comparably limited range put them behind hydrogen in that regard. From a consumer standpoint, it's got more to do with the charging time — because as Mears points out, "Hydrogen already has a head start benefit of almost instant refueling at a stop as compared with even high-power supercharging of BEVs."

That said, BEV technology has continued to change and grow. To the point that Professor Mears doesn't believe hydrogen will have that charging speed advantage for much longer. "...there are a lot of smart people working on these issues, and I expect to see a disruptive battery technology hit the market in the next 5 years that may change the segmentation rapidly," Mears says.

Infrastructure is also a major factor to consider, and while the Federal government does offer a hydrogen hub program, it's also investing in electrical charging with the DOE's National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program. Professor Mears points out that, despite the roughly $5 billion in funding going to a BEV charging network, "whether the national grid system can handle it is another concern."

Would it have been better for hydrogen cars won over BEVs?

While the competition between BEVs and hydrogen fuel vehicles isn't quite finished, and hydrogen has an opportunity to close the gap, it's difficult to know whether things would have been better if hydrogen pulled ahead first, especially since both technologies are still being refined.

"BEVs looked like the silver bullet that would slay emissions and carbon buildup in one shot, but once the reality of material availability (e.g., lithium, cobalt, and nickel), national electric grid capacity, the cost of supporting infrastructure, and consumer hesitation set in, manufacturers which had announced grand investments were suddenly backpedaling and opening their minds up to alternative platforms (which also includes traditional internal combustion engines, which are not going away anytime soon)," Mears adds.

And really, that's the crux of the challenge for both BEVs and hydrogen-fueled vehicles. Internal combustion engines are so entrenched that investments needed to move away from them tend to be discouraging. "Displacing ICE vehicles (which work really well for the market needs) will require investment and good communication about the benefit and motivation to drive consumer adoption," Mears notes.

Is hydrogen tech better suited for public transportation than BEVs? Or is there a different reason many cities invest in hydrogen-powered buses?

As Mears points out, in the case of both hydrogen fuel and BEVs, viability boils down to infrastructure. Gas stations are ubiquitous across most of the U.S. and for either alternative to become a true replacement, we'd need a similar level of "every corner" availability.

Mears believes public transportation — particularly having a more centralized space for entire fleets of vehicles to return to each day for refueling — may be the more reasonable recipient market for such a change. "Charging is a key barrier there," Mears states, "and a centralized hydrogen supply may have an advantage."

Right now, it's difficult to predict which possible gas alternative will come out on top. Even other outlier alternatives like alcohol have potential, according to Mears, who explains that these kinds of "dark horse" technologies, "could also take the market by surprise – these are more readily sourced, with control strategies and engine design considerations now under study that could make them a competitive technology for such fleet applications."