Project Iceworm: The Pentagon's Secret Base Under The Greenland Ice

In the middle of the 20th century, global war drove the development of nuclear capabilities. Following the success (such as it was) of the Manhattan Project, the United States and much of the rest of the world became increasingly interested in the potential of nuclear armaments, triggering a Cold War between the United States and the then-Soviet Union.

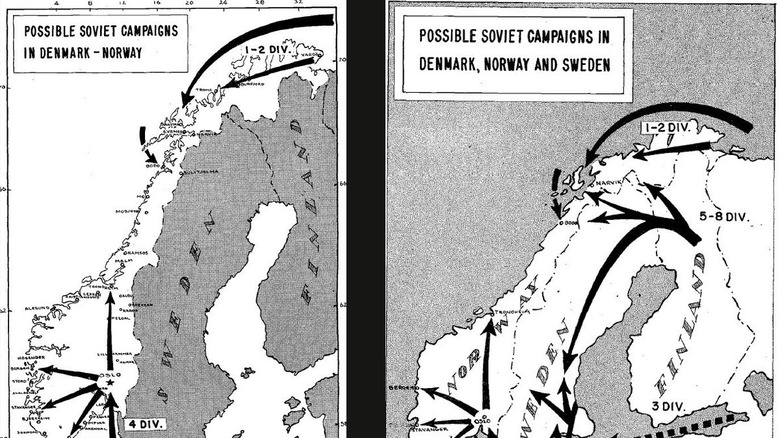

Part of the U.S.' nuclear strategy was spreading missiles outside the country to strategic points around the world. The plan had two strategic advantages — the first was that the United States could launch nuclear missiles, if needed, from locations within striking distance of the Soviet Union. The second was that spreading out the nuclear arsenal made it more challenging to locate and destroy.

To that end, in the 1960s, the U.S. military built a semi-permanent city inside underground tunnels carved into Greenland's ice sheets. Officially, a scientific research station was testing construction methods in the region's icy environment and doing climate science. In actuality, the frozen city hid a potentially deadly secret.

The Defense of Greenland Agreement

Despite its name, Greenland is largely a frigid and sparsely inhabited place under the umbrella of the Kingdom of Denmark. While it's not the sort of place that attracts a lot of full-time residents, one of the most crucial things for any military base is its location. You might not want to live there, but Greenland's position in the Atlantic makes it a strategically valuable staging ground. So much so that, in 1946, the United States made an offer to buy Greenland straight up in exchange for $100 million in gold (about $1.5 billion today) and access to Alaskan oil, according to NPR.

That offer was rejected, but the U.S. found other ways to use Greenland for military operations. In 1951, the United States signed on to a Defense of Greenland Agreement, which allowed NATO members to utilize Greenland for military operations, including the construction of bases and other installations.

Over the following decade, the United States built three military bases, two of which have since been abandoned. Only the base originally called Thule (pronounced too-lee) Air Base remains in operation today. In recent years, the base was renamed Pituffik (pronounced bee-doo-feek) Space Base, and it remains the U.S.' northmost military installation, standing less than 1,000 miles from the North Pole.

Camp Century

By the late '50s, Greenland was already well-established as a strategic military location for the United States. It had been used as a refueling station and radar installation, but the U.S. military had bigger plans for the icy island nation. In 1959, the Army Corps of Engineers scouted an area for a secret nuclear project under the cover of a project called Camp Century.

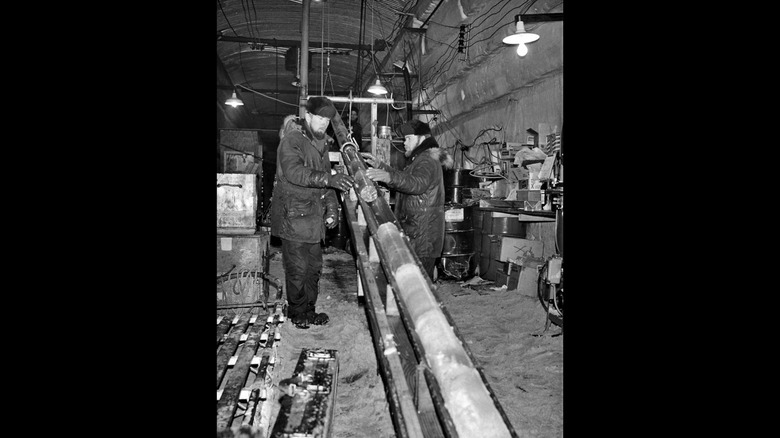

Officially, Camp Century was a scientific research station operated by the U.S. military. Its official mission was to carry out various types of research, including climate studies. To its credit, Camp Century did produce some important science, including some of the first ice core studies, which are still informing global climate science today. Authorities even made a propaganda short film about the fake purpose of Camp Century.

The real intended purpose was to hide hundreds of missiles equipped with nuclear warheads beneath the ice. The name of Camp Century refers to the original plan to build the site within 100 miles of the edge of the ice cap, but eventually, it was placed about 150 miles from Thule Air Base, now Pituffik Space Base.

Building the city

In order to support both the official and clandestine purposes of Camp Century, it was constructed roughly 150 miles away from Thule Air Base (now Pituffik Space Base) and roughly 125 miles from the coast of Greenland. The city was built from scratch over the course of 17 months between June 1959 and October 1960.

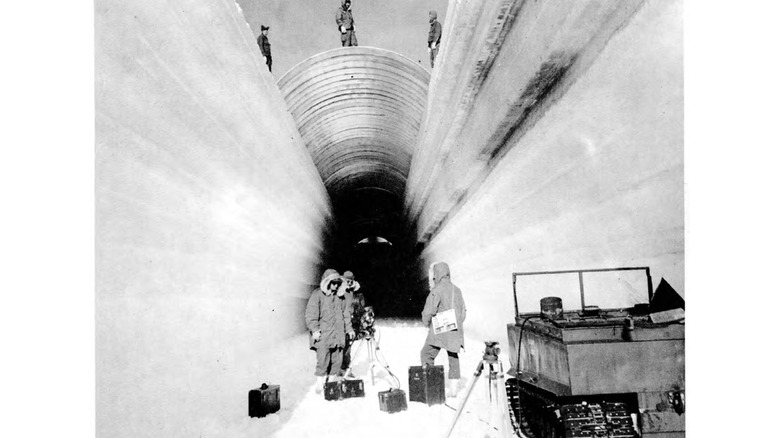

Before construction could begin, Army Engineers had to build a road across the ice and use sleds to transport some of the larger equipment. Heavy equipment (of which there was plenty) had to be moved using slow-moving sleds with a maximum speed of two miles per hour. The idea was to hide the entire installation beneath the ice, so building on the surface was out of the question. Instead, engineers used plows to dig trenches dozens of feet deep and hundreds of feet long. Those trenches were then covered with metal and buried under snow and ice.

In this way, hundreds of soldiers could live and work beneath the ice, completely shrouded from the prying eyes of the Soviet Union and everyone else, for that matter.

The underground nuclear city

During the 17 months of construction, Army Engineers dug out 21 steel-covered trenches spanning nearly two miles in total. The longest single trench, commonly referred to as Main Street, ran more than 1,100 feet from one end to another.

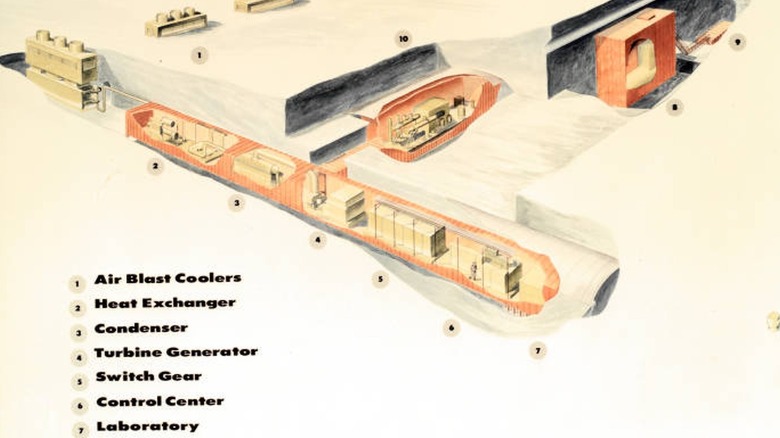

Main Street was as good a name as any because the trenches served as streets or thoroughfares within which prefabricated buildings were placed. Once construction of the initial camp was completed, the city permanently housed up to 200 people, providing everything they might need for a long-term stay. The trenches of Camp Century housed dormitories, a kitchen and eating areas, a hospital, laundry services, communications stations, latrines and showers, a theater and a library, a hospital with an operating room, a barbershop, and more! They even had plumbing.

Inside one of the trenches, engineers drilled a tunnel into the ice, creating a well that melted ice into fresh water and delivered it 500 feet to the surface. The only other thing they needed was energy, and they got that from a specially built nuclear reactor.

Camp Century's nuclear heart

The underground city was powered by a PM-2 nuclear reactor, the first of its kind. During this period of atomic experimentation, the United States government was keen to build bespoke reactors for their various projects. Less than a decade before Camp Century, the United States constructed the world's first nuclear-powered submarine, the Nautilus, complete with its own custom-made nuclear reactor.

The PM-2 reactor used only 44 pounds of uranium to power the entire city, providing electricity and hot water to the 200 residents. It's estimated the reactor had the same power capacity as roughly a million gallons of diesel fuel.

Despite the reactor's 330-ton total weight, it was considered a mobile reactor, capable of being disassembled, moved, and reassembled if needed. Each of the pieces, while large, could just fit inside of a cargo plane. The first pieces arrived in July 1960, just after construction began on Camp Century, and it powered the city for a couple of years before it was abandoned. It's probably best that the project was ultimately scuttled because the reactor reportedly leaked neutrons and contaminated cooling water, the surrounding ice, nearby objects, and people.

Project Iceworm

While the project only lasted a few years beneath the Greenland ice sheet, the cover story about its purpose remained intact until an investigation by the Danish Parliament revealed the truth in 1997. The plan was to eventually carve thousands of miles of tunnels under the ice.

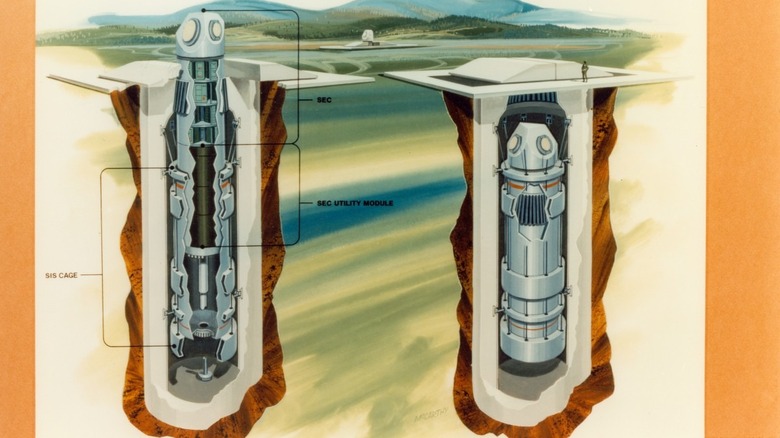

In addition to the scientific and living facilities already in place at Camp Century, engineers would have set up 2,100 missile silos and 60 nuclear missile launch control centers. All of that extra machinery would have required a much larger staff, estimated at up to 11,000 soldiers. All of that infrastructure was intended to support an arsenal of 600 nuclear missiles.

If you're thinking that's a small arsenal for 2,100 silos, you're right — that was part of the design. The thinking behind Project Iceworm was that the missiles would be moved regularly using railcars inside the tunnels. That way, it would never be clear to anyone outside where the missiles were, so there would never be an obvious point of attack.

Meanwhile, the missiles could remain armed and ready to deploy. All of those layers of subterfuge were intended to ensure that Project Iceworm survived, even in the event of a nuclear attack, allowing the United States to retaliate in a nuclear conflict.

Abandoning Camp Century

There were a lot of reasons Greenland seemed like a good place for Project Iceworm. Its location on the map made it a nice stopping point in the Atlantic, and its icy climate was also advantageous. The surface has a minimal incline, allowing Army Engineers to confidently dig level trenches. Moreover, the ice was expected to remain stable for a long time. Unfortunately, engineers were wrong on that point.

Within three years, scientists at Camp Century realized that the ice was moving more quickly than expected. At the time, they estimated the tunnels would become unstable within a couple of years; the city was on borrowed time.

Because of the newly discovered instability, the idea of storing a nuclear arsenal under the ice sheet became a nonstarter. Even the idea of maintaining the camp's existing nuclear reactor became increasingly unsafe. Ultimately, the decision was made to shut the project down. Soldiers packed up the essentials, decommissioned the reactor, and left.

Coming to light

Part of what made Project Iceworm so appealing was its potential for secrecy. Even when it was abandoned, scientists at the time assumed that all traces of the camp would be swallowed by the ice forever, taking the secret of its true purpose with it. Knowledge of Project Iceworm remained buried in the ice until 1997 when the Danish government released an official report about the secret military program at Camp Century.

The report outlined the plans for Project Iceworm in detail, as well as the fact that the project was undertaken without the knowledge or approval of the Danish government. While the Danes agreed to the use of Greenland for United States military operations, they likely would have objected to the storage or usage of nuclear weapons from their soil.

The strategic advantage, however, proved too tempting. Because of Camp Century's proximity to the North Pole, an arsenal of Iceman missiles could have made contact with roughly 80% of potential Soviet targets. Fortunately, that's an eventuality that never came to pass.

Radioactive legacy

Once the United States military realized that Camp Century was unsustainable, they packed up and got out of dodge. The facility was entirely abandoned by 1967, only eight years after the site was first scouted and construction began. When the military left Camp Century, they took the bare essentials, including part of the nuclear reactor, but they left a whole bunch of other things behind.

Of the reactor, only the reaction chamber was taken away. The rest were abandoned at the camp, along with the accumulated waste of hundreds of people. When the last person left Camp Century, they left behind buildings and other physical infrastructure, barrels of liquid fuel, thousands of liters of human waste, and a disturbing amount of radioactive waste.

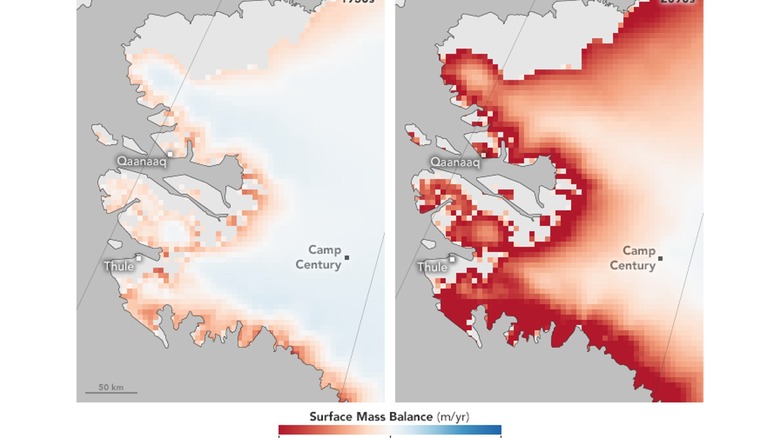

At the time, it was thought that the shifting ice and frigid polar climate would bury the base in the ice forever. Unfortunately, that has not been the case. According to a scientific study published in 2016, shifting ice sheets and warming global temperatures could release all that waste into the ocean or aquafers. They also suggest that Camp Century may be a proverbial canary in the coal mine, highlighting the danger of unsecured and aging infrastructure threatened by climate change all over the world.

Lessons learned

The brief existence of Camp Century and its enduring legacy, both good and bad, is a testament both to humanity's boundless ability to do the seemingly impossible and to our hubris. That scientists and engineers succeeded in the 1960s to construct a self-sustaining nuclear-powered city beneath a polar ice sheet is nothing short of incredible.

The lessons learned are far-reaching. Already, the ice core science done at Camp Century informs ongoing climate science. The camp's stated mission, to explore methods of construction and habitation in harsh climates, was a qualified success. Camp Century was, by many measures, a city of the future, existing in an impossible place on a seemingly magical and recently tamed nuclear fuel source.

At the same time, the project failed because of a fundamental misunderstanding of the environment and a lack of respect for the power of nature. From a certain point of view, that's the story of humanity's relationship with nuclear power in a nutshell. If Camp Century taught us anything, it should be that we should deal with nuclear power and with the planet a little more carefully.