Are Video Game Emulators Illegal? Here's What The Courts Have Ruled

If you've been keeping up with video game news, then you may have heard about how Nintendo sued the makers of Yuzu, a multiplatform Nintendo Switch emulator, before agreeing to settle for $2.4 million a week later. If you have any familiarity with the video game console emulation scene, or maybe even if you don't but only read surface-level takes, you may be confused as to how and why this was possible. The conventional wisdom is that emulators themselves are legal and it's distributing the console software (games, BIOS, copy protection keys, etc.) that crosses a line.

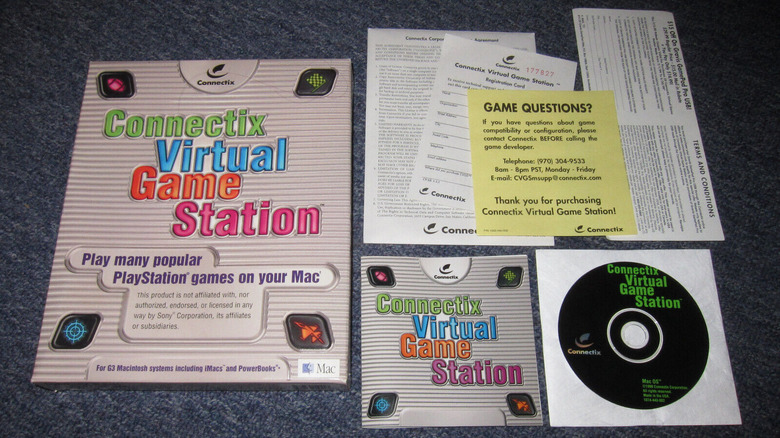

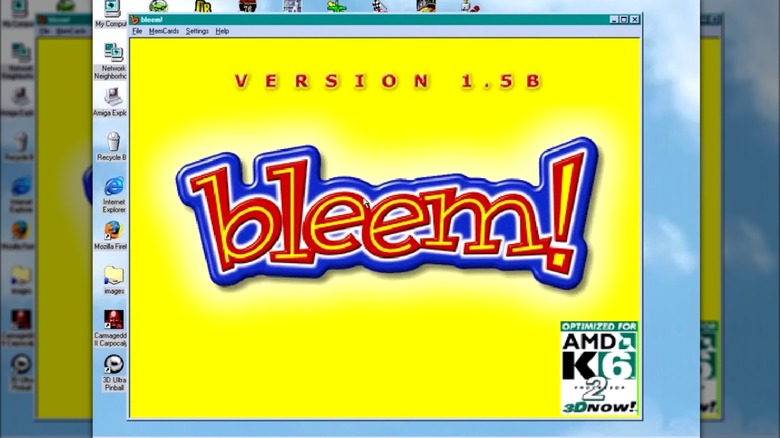

How did we get there? Court cases in the very late 1990s and very early 2000s initiated by Sony against a pair of PlayStation emulators that were sold at retail set some precedents that have largely been followed ever since. There are no copyright laws that are granular enough to definitively weigh in on emulation's legality, but the case law is clear enough to set a clear blueprint. If there is no previously copyrighted code like BIOS included, whether because the console didn't have BIOS, the emulator devs reverse-engineered it, or they simply released the emulator without it, then that emulator is presumed to be fully legal.

Which emulators drew litigation?

In a segment about emulation on "CNET Central" circa 1998, GameCenter.com editor John Marrin argued that the game industry was more concerned with the eventual emulation of current consoles than classic ones. That was prophetic, with Sony filing lawsuits in the first quarter of 1999 after the releases of Connectix Virtual Game Station and Bleem. Notably, these emulators could run current games at full speed and were also sold in stores. PSemu, an existing freeware PlayStation emulator, required a non-bundled copy of the system BIOS and wasn't targeted.

Per a 2017 Eurogamer article, Connectix had approached Sony about collaborating on the VGS as a follow-up to Virtual PC, an Intel/x86 emulator for running Windows on PowerPC-based Macs, but was rebuffed. Connectix, instead, reverse-engineered the PlayStation BIOS to make a non-infringing emulator. Bleem's much smaller development team had no idea what Connectix was doing, but the Eurogamer article and other sources aren't clear on how they got around the BIOS past it being non-infringing.

Two weeks after Connectix won 1999's MacWorld "Best in Show" award, Sony sued, arguing that, among other things, VGS circumvented the PlayStation's copy protection and region lock. According to IGN at the time, this was false. Sony also sued Bleem several weeks later, with Eurogamer noting in 2017 that Sony's lawsuit was a mildly altered replication of the complaint against Connectix. Confusion about the lawsuits abounded since Sony made no profit on consoles, with Eurogamer speculating in 2000 that it was in response to Bleem's ability to run bootleg games.

How did the Connectix lawsuit go?

The first matter before the court was Sony's attempt to get a temporary restraining order against Connectix, with the ruling in Sony's favor coming on March 11, 1999. Federal Judge Charles A. Legge was then tasked with Sony's motion to upgrade the restraining order to a preliminary injunction, again ruling in Sony's favor on April 20.

At this point, Sony's main argument was that even if the released version of VGS didn't contain the PlayStation BIOS, Connectix had illegally copied it in the course of development, early builds of the VGS used it, and Connectix benefitted from illicit copying as a result. For a while, this worked, which meant that Connectix couldn't legally sell VGS. Connectix appealed, asserting that its intermediate copying of the BIOS was legally fair use in the course of developing its own, non-infringing BIOS. On February 10, 2000, the appellate panel ruled in favor of the VGS being fair use, setting the precedent that emulators were legal if not bundled with commercial copyrighted content.

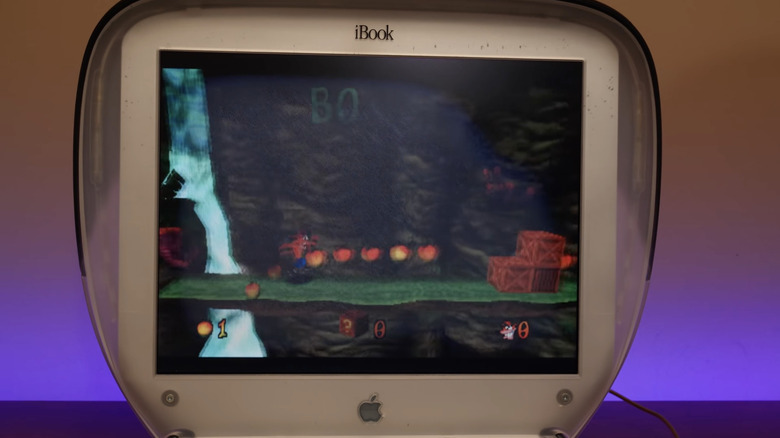

"We find that Connectix's Virtual Game Station is modestly transformative," reads the ruling. "The product creates a new platform, the personal computer, on which consumers can play games designed for the Sony PlayStation. This innovation affords opportunities for game play in new environments, specifically anywhere a Sony PlayStation console and television are not available, but a computer with a CD-ROM drive is." The lawsuit was eventually settled with, as reported contemporaneously by The Register, Sony buying the VGS copyright.

How did the Bleem lawsuit go?

Unlike in the Connectix case, Sony never really saw any victories for its argument that Bleem itself was illegal or infringing. In April 1999 The Guardian reported that the court denied Sony's request for a temporary restraining order. That order isn't online, explained in any detail in contemporaneous coverage, or explained in subsequent rulings, so it's unclear what drove the decision. However, Sony copying and pasting the Connectix complaint without investigating Bleem's technical differences may have been a factor. Two weeks later, Sony lost a bid for a preliminary injunction, which Bleem hailed as a significant victory in a press release, noting that Connectix lost at the same stage.

Subsequently, the Eurogamer article explains, all of Sony's counts about Bleem itself being infringing were dismissed, leaving just the claim that Bleem was infringing in its use of game screenshots on its packaging to showcase the emulator's graphical improvements over a physical PlayStation console. That argument was rejected in May 2000, with the appellate judge ruling that, though the screenshots were technically Sony's IP, "such comparative advertising redounds greatly to the purchasing public's benefit with very little corresponding loss to the integrity of Sony's copyrighted material." As outlined by the Eurogamer article, Sony's next move was to sue Bleem for patent infringement, a tort where the BIOS debate wouldn't matter. With legal bills mounting, Bleem gave up and eventually agreed to a settlement enjoining it from selling emulators.

How did these rulings affect emulation going forward?

Coming out of the Connectix and Bleem litigation, two things became clear: Barring the inclusion of copyrighted content, getting judges to rule that emulators themselves were infringing was an uphill battle. And console makers could easily intimidate emulator developers into surrendering via their significantly greater resources.

Thankfully, it seems like the former has stopped the console makers from filing unwinnable lawsuits or even sending out many legal threats. Nintendo, for example, never followed up on its stated intent to sue the developers of UltraHLE, a full-speed freeware Nintendo 64 emulator released around the same time as Bleem and VGS. The "Legal Status of Emulation" page on the Emu Gen Wiki outlines court cases relevant to emulation, but few direct legal threats or outright lawsuits are mentioned, with the two most relevant actions coming from Nintendo in 2023 and 2024.

In May 2023, Nintendo sent a legal threat to Valve that led to Dolphin, a GameCube and Wii emulator, being removed from Steam. According to an Ars Technica report, Nintendo focused on Dolphin's inclusion of the Wii Common Key to decrypt Wii game data, and the lawyer they spoke to felt that this gave the console maker a solid case. However, Nintendo hasn't sued or directly threatened Dolphin. The emulator's devs noted in a blog post weeks later that, having consulted an attorney, they felt they were on firm legal ground since the Wii Common Key was in Dolphin's public source code for over 15 years without Nintendo objecting.

Enter Yuzu

It took decades for Nintendo to find an emulator with developers that its lawyers were willing to take to court. That's Yuzu, a multiplatform Switch emulator, which the console maker sued in February 2024 before agreeing to settle a week later. In the complaint, though not central to Nintendo's legal argument, the console maker's lawyers outright claimed that an emulator "allows users to unlawfully play pirated video games that were published only for a specific console on a general-purpose computing device." This bore a strong resemblance to comments that Nintendo made during the UltraHLE tiff in 1999. "Emulators such as this are illegal," said Nintendo spokesperson Beth Llewelyn in a statement to TechWeb at the time. "It promotes continued piracy."

Nintendo's actual legal argument focused on Yuzu including instructions for how to download the Switch decryption keys needed for the emulator to function. Yuzu didn't include them, but Nintendo was confident enough to move forward with the argument that the instructions constituted circumvention of the Switch's encryption. Speaking to ArsTechnica, Jon Loiterman, a lawyer specializing in gaming, seemed confident that Yuzu's actions were a far cry from circumvention, but was not bullish on the devs fighting the lawsuit. "Unless Yuzu has very deep pockets, I think they're likely to take it down, and the software will live on but not be centrally distributed by Yuzu," he said.