For autonomous cars, driving dumb is key

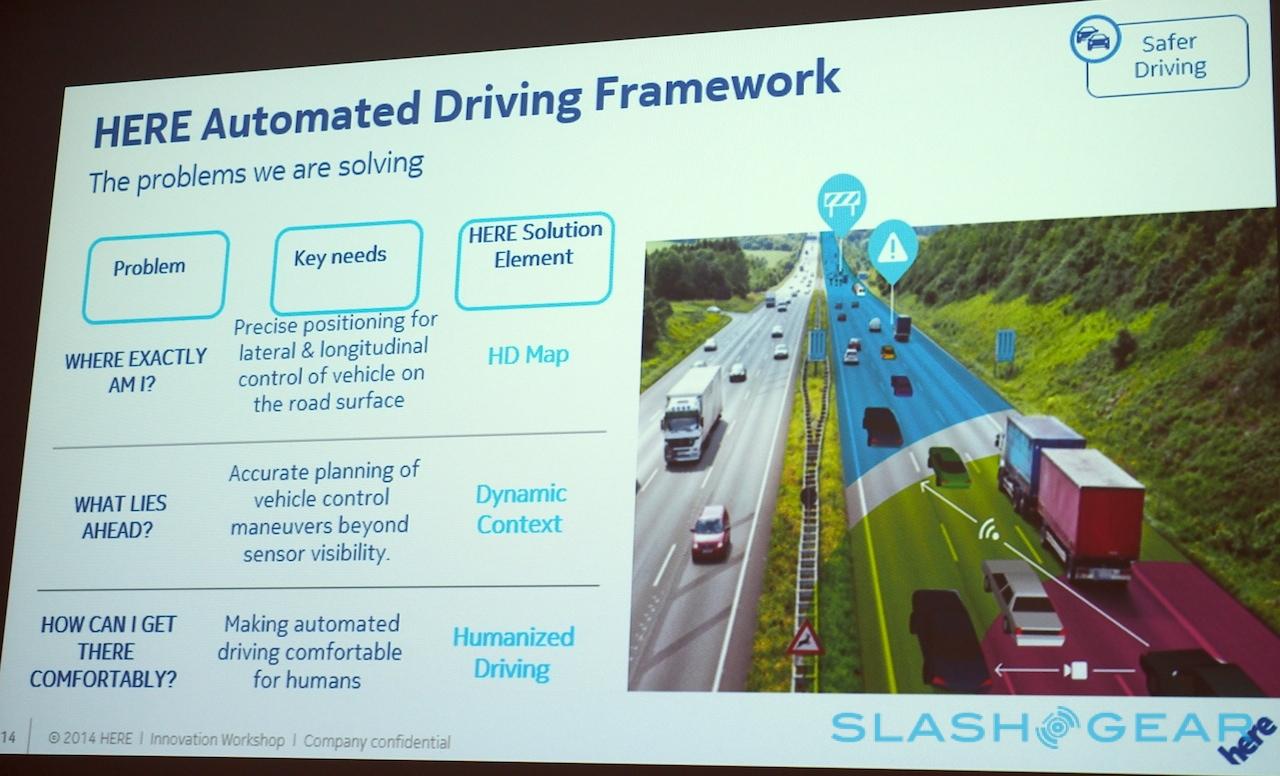

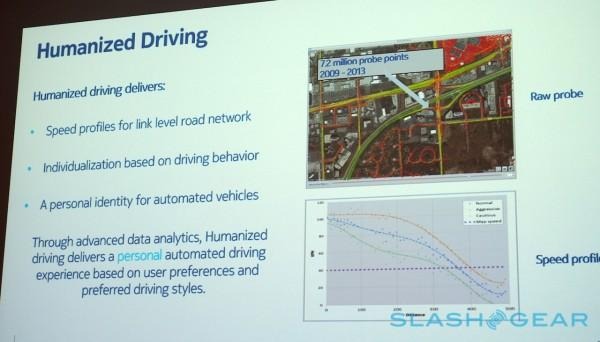

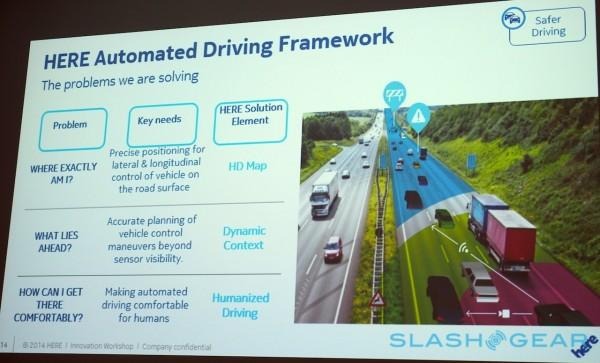

Self-driving cars may need to show some self-restraint when it comes to their "better than human" reflexes and abilities, the Nokia HERE team working on autonomous vehicle technologies suggests, if their flesh and blood passengers are to accept an AI taking the wheel. HERE calls it Humanized Driving, giving computer-controlled cars similar characteristics to the people they're replacing so as to preserve a feeling of normality, even potentially becoming a virtual twin with the same style as the car's owner.

Think of it, perhaps, as the autonomous vehicle equivalent of the Uncanny Valley phenomenon, where as artificial people grow more convincing, so our levels of discomfort with them skyrocket.

For cars taking over responsibilities on the road, there's a similar line to run. Drive too well, too efficiently – too much like a computer, in effect – and it only serves to highlight the scale of the difference between the vehicle's brain and our own. Rather than becoming a beyond-human proficiency we can trust, it instead runs the risk of leaving us jittery and uncomfortable.

To figure it out, VP of Connected Driving Ogi Redzic explained to SlashGear, the HERE team has been tracking data from thousands of drivers, aggregating how they individually tackle the same roads and junctions.

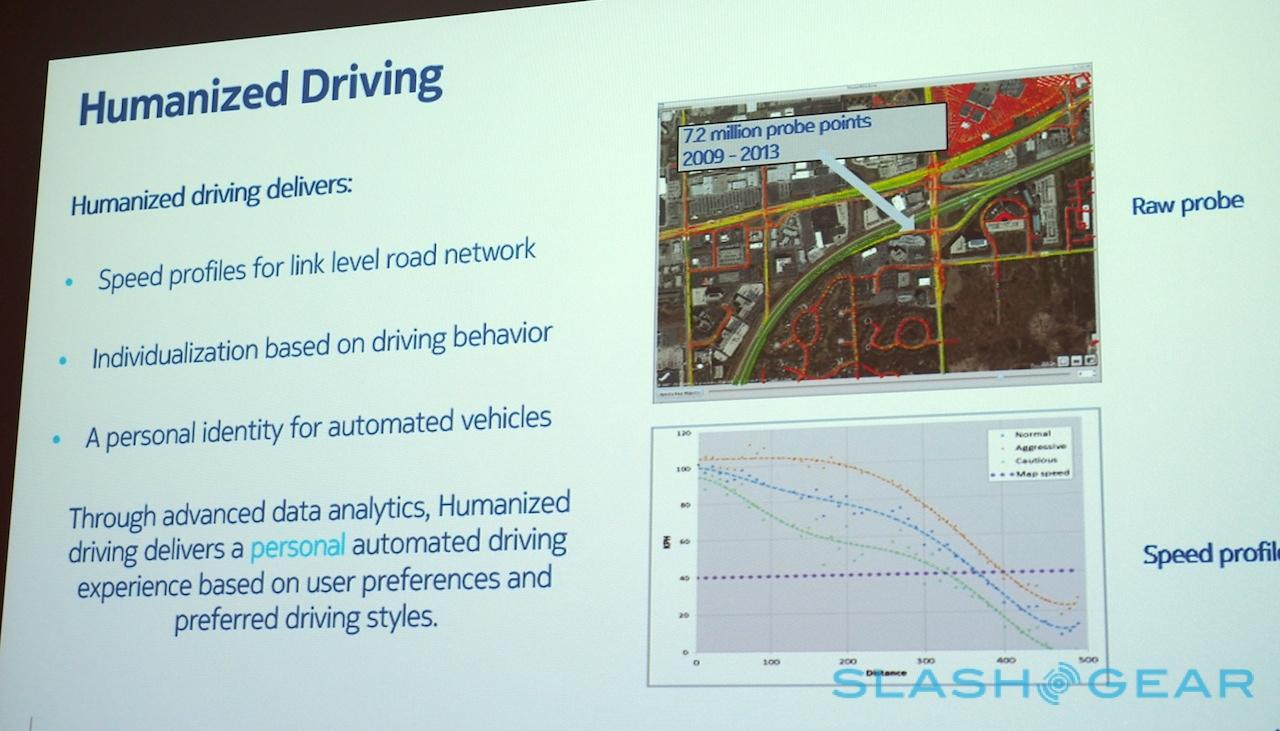

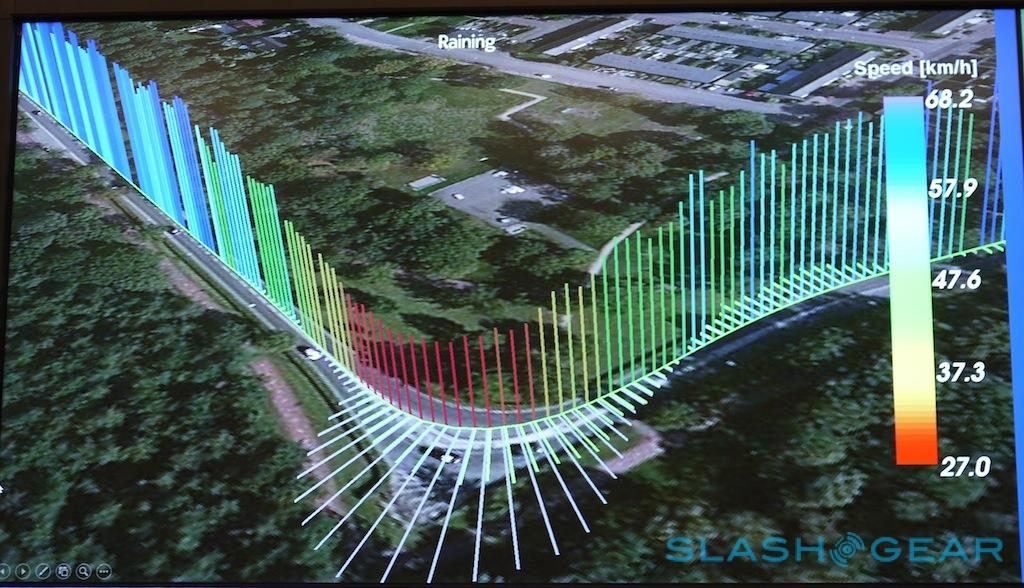

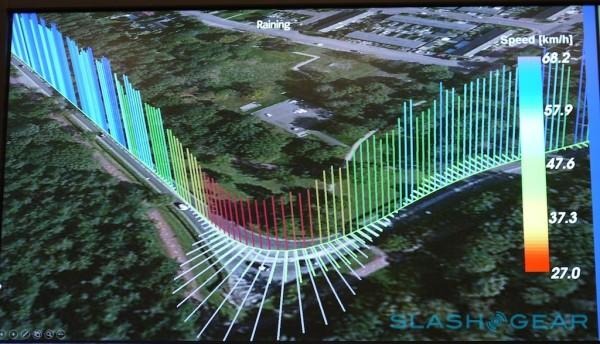

For instance, looking at a highway offramp where the speed limit drops to 40mph, Nokia was able to differentiate drivers into three groups based on how quickly they began braking: aggressive, normal, and cautious.

What was particularly interesting, however, was that all three groups continued to decelerate even after they'd hit the new speed limit, regardless of whether they'd approached the ramp aggressively or cautiously. The team's assumption is that, despite the legal maximum, human drivers feel safer going slower still.

Nokia HERE: Smart Cities, Ethical Tracking, and Self-Driving Cars

On paper, a self-driving car wouldn't have to show that same restraint. It could linearly cut its speed to the new limit and then stick to it for the remainder of the ramp, relying on machine smarts to do so safely.

Whether those in the car would feel safe is another matter, Redzic points out. By ignoring the perception of those onboard, the concept of an AI in charge might end up being tougher to stomach, than if it borrowed the less efficient but more familiar approach of a human behind the wheel. In short, following a less linear route to the new limit, and then further reducing after that.

That's not to say your autonomous car need necessarily mimic the median driver; in fact, there might be a better shortcut to acceptance. HERE envisages a time when a car might learn the driving style of its owner, building up "a personalized identity," suggests Redzic.

For the initial period of ownership, for instance, the driver could in effect teach the car's AI how they prefer to drive by example. When they feel comfortable braking in corners, or accelerating off the on-ramp, and how much space they prefer between them and the traffic around them.

After that, the car itself would adopt those driving styles: hit the "Autonomous Mode" button on the dashboard and a virtual "you" would take over the wheel, potentially indistinguishable yet never tiring or getting road-rage.

Nokia HERE 3D v2: We ride the car putting Google Maps on notice

Of course, the manner in which you drive when you're on your own, or in a rush to make an appointment, can be very difference from when you have your kids in the car. One possibility, HERE's Redzic suggestions, is that autonomous vehicles could have not one but multiple personalities, user-selectable depending on the current conditions.

So, there might be a "safe mode" in which the car is more cautious and conservative, but an "aggressive" mode that could trim the distance between other vehicles, be more proactive in changing lanes and overtaking, and accelerating with a greater sense of urgency. In-between might lie a number of alternatives, Redzic predicted, like "late to work," "cruising," and "no fast movements."

Mercedes-Benz already has self-driving cars powered by HERE on the road

"There is no way that this technology will get adopted with a one-size-fits-all approach," the Connected Driving VP argues, though he does believe that attitudes will change over time as we get more familiar with a digital chauffeur. For instance, as the driver-turned-passenger spends more time with the car taking command, they're likely to trust the AI more and thus reduce their expectations around things like late-corner braking and traffic spacing.

Redzic predicts that we'll see examples of highly automated driving on the market in five years time, though fears that mass adoption could prove hamstrung by something even dumber than dumbed-down AIs.

Right now, he points out, the legal framework surrounding self-driving cars lags far behind the technology: who is liable if an autonomous vehicle crashes, or if in the case of an inevitable collision it opts to save its own passengers at the expense of pedestrians or other road users, or indeed vice-versa. Securing a degree of comfort for the lawyers may prove altogether more difficult than for those replaced at the controls.

"We've still got time to talk about these things," Redzic concluded, "but we don't have much of it."