Movie Review: Tron (1982)

In the run-up to the new Tron sequel, which opens nationwide this Friday, I decided to dust off my old copy of the original 1982 film to see what I'd forgotten, and to determine if the original movie still holds up after almost 30 years. In some ways, the original was groundbreaking. It was infamously excluded from Oscar consideration for the best visual effects category because the use of computer animation was considered cheating. But in many ways Tron is quite derivative of some of the more popular sci-fi movies of its age, most notably the Star Wars movies that had been released by then. Still, it's a fun film to watch, and it offers an interesting preview into what the new sequel might hold.

Foremost, I had forgotten the plot of the original Tron. I remembered that Jeff Bridges' character, Flynn, had been sucked into the computer world by a giant laser beam, and I remembered that the world was being controlled and manipulated by a huge enemy called the MCP, or Master Control Program. But I had forgotten the encapsulating story.

The movie is, at heart, about a video game company. We start with Flynn trying to hack his way into a company called Encom to find evidence that the company's best selling creation, a game called "Space Paranoids," was actually Flynn's idea, stolen by the company's Senior Vice President.

Actually, I'm getting ahead of myself. We really start in the arcade, where the hand of an unseen player feeds a quarter into the slot of a video game called "Lightcycle." Then, the action fades into the metaphoric video game world, where the action is played out by programs in more or less physical representations of the games.

More on that later. After a quick, brutal round of Lightcycle, we're with Flynn, and his program Clu, who looks exactly like Flynn in a yellow Tron suit. Clu is Flynn's program, searching the Encom database for a file that will prove Space Paranoids was stolen by the Encom exec. Clu is denied and destroyed by the giant computer overlord, the MCP, and his minions, which causes an internal investigation in Encom in the real world.

Some of Flynn's old Encom friends suspect his involvement in the hacking, so they visit him at his arcade, where he shows off his champion video game prowess and lives in a bachelor pad above the blips and bleeps of 1980s twitch gaming. These friends are quickly convinced to help Flynn break into Encom, giving him access to a terminal that will help him find the file. Of course, this terminal happens to be seated across from a gigantic laser beam that can somehow transform ordinary objects into computer programs, and back again. Oops, they probably should have warned him about that.

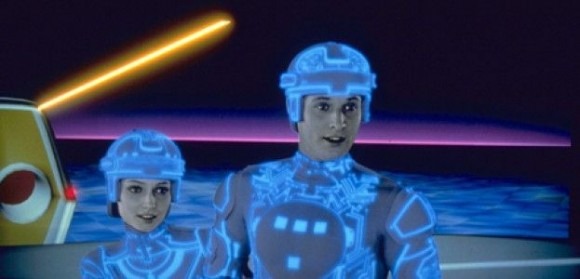

The MCP digitizes Flynn, and the race is on. He becomes a player in the digital gaming world, then an insurgent, trying to destroy the MCP's hold on the stored data, with the help of some other programs. These programs, of course, are actually the digital metaphors of his friends in the real world. Not quite avatars, per se, more like programs that bear the unique stamp of their owners, including their faces and likenesses.

In the digital world, the programmers, or "Users," are so godlike that the programs refer to them as deities. In fact, there is even doubt that these Users exist, and if so, are they a benevolent force with a plan, or do they even care about their creations? At times, the pseudo-theology is charming, but at other times it can be rather goofy.

In fact, the entire movie can be somewhat silly. Surprisingly, the movie takes itself much more seriously in the digital world than it does in the real world. In the real world, Jeff Bridges plays the character as a hapless goof ball. In the digital world, you get the impression that there is much more at stake. In the real world, the plot is about finding evidence to sue a company for intellectual property theft. In the digital world, the plot is about freeing a society from religious persecution and restraints on basic civil liberties, especially freedom of speech.

Of course, Tron was released between the Star Wars movies "The Empire Strikes Back" and "Return of the Jedi," and it borrows heavily from Star Wars, both in terms of plot devices and narrative structure. There are gigantic ships that fly endlessly overhead. The disc fighting in Tron is reminiscent of the lightsaber battles in Star Wars. Even the characters are similar. You have the flying-by-the-seat-of-his-pants Flynn, who is charismatic and capricious, helping out the much more boring and almost religiously focused Tron. You have little robotic characters with more personality than verbiage. You've got a female love interest who is ambiguously attracted to Tron and drawn to Flynn's bad-boy attitude.

You've got a wizened old man who guards the sacred knowledge. Oh, and the bad guys wear helmets, and converse in secret chambers with an unseen overlord whose power is unimaginable. The end battle scene involves the main character, Tron, aiming a single, precision shot at just the right spot on the gigantic evil nemesis. I could go on and on.

I haven't seen the new movie yet, but if the original borrowed heavily from Star Wars, I'm guessing the new film will borrow heavily from The Matrix. While I liked The Matrix, and I even enjoyed the sequels (though not as much), I hope the new Tron: Legacy avoids this folly. While it would seem that the movies are close cousins, with a hero who is trapped in a virtual world, in fact this isn't exactly what Tron is about.

The world into which Flynn falls is not a virtual version of our own world. It's a metaphor of the relationship between human users and computer programs. It doesn't need to be picture perfect, or even representative of anything real or human. It should always be outlandish, more than otherworldly, perhaps extra-dimensional. The Matrix was meant to be a stylized replacement for our own world. The world of Tron is an anthropomorphized video game.

I also hope Tron: Legacy doesn't lose all of the silliness of the original movie. Sure, the dialogue and direction were stilted and confused. But there were some moments that were clever. Useless financial accounting programs, past their prime, are forced to duel to the death in a game of digital jai-alai. The MCP started as a chess program that grew too big for its own britches.

Tron even prefigures some interesting modern issues with technology. Flynn is unable to hack into Encom's database because he does not have enough access. The real hacking he accomplishes is by gaining access to people within the organization itself. This is how the best hackers operate today. Rather than brute force attacks, driving a virtual tank up to the gates of the walled garden, hackers are much more likely to try to get information from real people first who can be used to access a system.

The problem within the Tron world is that information cannot enter or leave. The world has become stagnant and dead without a connection to the outside. We're considering the same problems with internal networks, and especially social networks, today. Is it better to cut off employees' access to the outside world? Does it help with productivity and security, or does it just leave employees feeling isolated, perhaps looking for another way in or out?

Finally, the real stakes in the game are not with Flynn's quest for retribution. Early on, the MCP hints that it wants to gain more and more control over the world and its affairs, until it is finally making real political decisions faster and more efficiently than a human ever could. While this idea, of computers taking over the world, is echoed in plenty of stories to come later (Terminator, anyone?), it's more subtle in Tron. It isn't about giving a computer control over the military, it's about giving away control over the access to information. Especially in this day and age, we're seeing that this might be a much more powerful way to subvert authority.