HTC Vive hands-on: That Valve VR wow-factor

I'm going to be blunt with you, words can't do justice to the experience of using HTC's Vive virtual reality headset. There's nothing quite like slipping into a virtual 3D world, as I did this week in a preview of Vive ahead of developer units shipping this spring. Cloistered in a room at the back of HTC's Mobile World Congress stand, and with the reassuring voice of a Vive engineer whispering in my ear, I got to try out a number of demo apps and environments created for the platform by Valve and others, including the first announced title for SteamVR.

Vive was the surprise bonus at HTC's keynote on Sunday, putting even the much-rumored reveal of the HTC Grip wearable in the shade. What makes it special is not only how it creates a 3D virtual world for you to immerse yourself in, but in how that world interacts with the physical space around you. As you move around room up to 15 x 15 feet, two laser emitters are used to identify exactly where you, and where you're looking, Vive then translating that to movement within the 3D environment.

Hardware and Comfort

Vive itself – still a prototype at this stage – resembles something like Oculus Rift at first glance: a large, matte plastic eyepiece and three stretchy straps which hold it in place over your eyes. I was able to wear it with my glasses still, though – as I found with both Rift and Sony's Project Morpheus – it did push the nosepiece somewhat uncomfortably against you nose; your mileage will probably depend on the design of your glasses.

Studding the outside are dozens of slightly-recessed sensors, each small square using laser tracking from two beacons mounted high up in the corners of two opposite sides of the room to track position. On the top, there's a USB 2.0 port, USB 3.0, and full-sized HDMI, for connecting to the computer that drives the experience. The two eyepieces each have a 1200 x 1080 resolution panel with a hefty 90fps refresh rate.

While Vive will work with a space up to 15 x 15 feet, it needn't be that large. In fact, it can be calibrated upon startup to suit a smaller space if that's all you have; even down to a single chair. HTC plans to package a 5 meter cable in the box, to suit each.

Also accompanying the headset is a pair of wireless VR controllers, each resembling a short baton with a cluster of even more sensors on top; they're a little like a PS Move controller, though the sensor section is larger than Sony's glowing ball. In all, there are more than seventy sensors across Vive and its controllers. A trigger button falls under your forefinger, while a circular touchpad which also acts as a button is on the front, under the thumb.

For my demo, I worked through roughly eighteen minute of different scenes, games, and experiences. I was also surrounded by a fair number of cables: while the production Vive will demand a physical connection to your PC, at this point HTC's controllers are also wired, and there's a battery belt that I wore slung around my hips, too.

Audio, meanwhile, came from a pair of headphones that plugged into another socket on the back of the headset. That's how it will play out on the developer version, too, though HTC will integrate earphones into the consumer Vive in the name of simplicity.

I should also point out that HTC didn't allow us to film the demo, either myself moving around the room or any of the content I was seeing. Some of the developers involved in the highlight reel have screenshots of their software, but they're obviously not going to give you the same impression as you get from actually using Vive.

The Vive Experience

My first view could be described as a launcher amphitheater: SteamVR's Controllers intro, effectively a large, white space delineated with pale lines, and with framed apps floating in a circle around me. Turning, I could see them arrayed around me, or look up at the infinite white sky. However, as my HTC guide quickly pointed out, I could also walk around the virtual space by moving in the real-world.

That instantly makes Vive feel more immersive than most of the other virtual reality headsets I've tried, in which you navigate by jabbing a stick on a gamepad. Since you're completely blind to the outside world, HTC has to warn you if you're getting near a physical obstacle like a wall (the expectation is that you'll move any furniture out of the way first). In the VR environment, a glowing blue grid suddenly flickers into life in front of you if you get too close to the arena's limits. Less bound were the balloons I could inflate from the tip of the left controller, choosing their color with a color-wheel on the control pad, and then batting them away with the other hand.

Segueing into an area of different height hexagonal columns, developed by HTC Creative Labs, I was able to walk around between them, the columns themselves dropping into the ground as I neared and then springing up again behind me once I'd passed by. Again, if I got too close to the physical limits – the virtual world stretched out into the distance – the wall grid would appear as a gentle reminder of how far I could roam.

What struck me from the get-go is how little lag or judder there was. As you turn your head, there's no sense of disconnect between what you see on screen and what your senses tell you about how the world ought to be moving. You can look up, or down at your feet – it's a little disconcerting not to be able to see your body, and not every environment I tried supported or required the controllers, which ordinarily float like disembodied hands in front of you – or quickly glance over your shoulder, and even with fast twists of my head I didn't feel nauseous or uncomfortable.

That proved important in the next environment, a shipwreck under the sea, one of the decks of which I had freedom to explore. Dubbed TheBluVR: Encounter and the handiwork of WEVR, I could peer off into the depths of the murky blue gloom, but walk no further than the wooden railing; however, as I experienced in Sony's underwater demo on Morpheus, I was able to lean over the edge and look down at the deeper water.

Meanwhile, schools of tiny fish swam around me, and if I jabbed at them with the controller I could frighten them away. Less skittish – or perhaps just programmed not to respond to me – were the rays that occasionally glided above me.

My first disappointment was in bumping into Vive's limits. I'd wanted to duck under a fallen mast – it takes a mental twist, but when you realize you can crouch down and around objects, all of a sudden the whole experience starts to feel more real – but before I could, the wall warning flashed up. Presumably, actual games will figure out some way to rationalize that issue.

I didn't have time to ponder it, though; when I glanced back over my shoulder, I realized that a huge blue whale had swum up next to the railing. I was able to get up close to its eye, and examine the barnacled length of its fin as it beat lazily near me; there was a palpable sense of its heft, to the point that I ducked back when it moved past me so as not to be struck in the process.

There's no vibration or other physical feedback system in Vive, but the high-resolution graphics and the audio proved to be enough that, when the waters around me started to darken and the ship to shudder as if about to plunge further down, I momentarily felt like I was losing my balance.

While exploring unusual worlds is one aspect of what HTC expects Vive owners to use the headset for, it's not the headset's only purpose. A demo of Owlchemy Labs' Job Simulator – the first publicly announced game using SteamVR – put me in a virtual kitchen, with cartoonish 3D objects like frying pans, chopping boards, and rolling pins, and oversized ingredients. A robot character dubbed Job Bot walked me through preparing a simple recipe: the controllers were now huge white hands like Mickey Mouse's gloves, which I could grab with by pressing the trigger.

The cookery challenge itself was simple, but the degree of flexibility in the world around me was surprising. When I'd played the virtual sword-fighting game with Sony's Morpheus, for instance, I'd quickly found you couldn't throw the sword or any other object away: let it go, and it would fall to the floor and reset to its original, grabbable position.

Maybe I'm not to be trusted in a virtual kitchen, but one of the first things I tried was throwing something. I'm also clearly clumsy, because I managed to knock an egg onto the floor – it smashed with a satisfying crack and splatter – and then there was a useful rolling pin which served as an excellent tool for bashing other objects.

The demo moved onto the next environment just after I dropped a frying pan (complete with the second egg I'd just about managed to salvage) because I assumed the game engine would be either generous enough or sufficiently low-resolution so as to not expect me to position it exactly right to put it down on the gas burner.

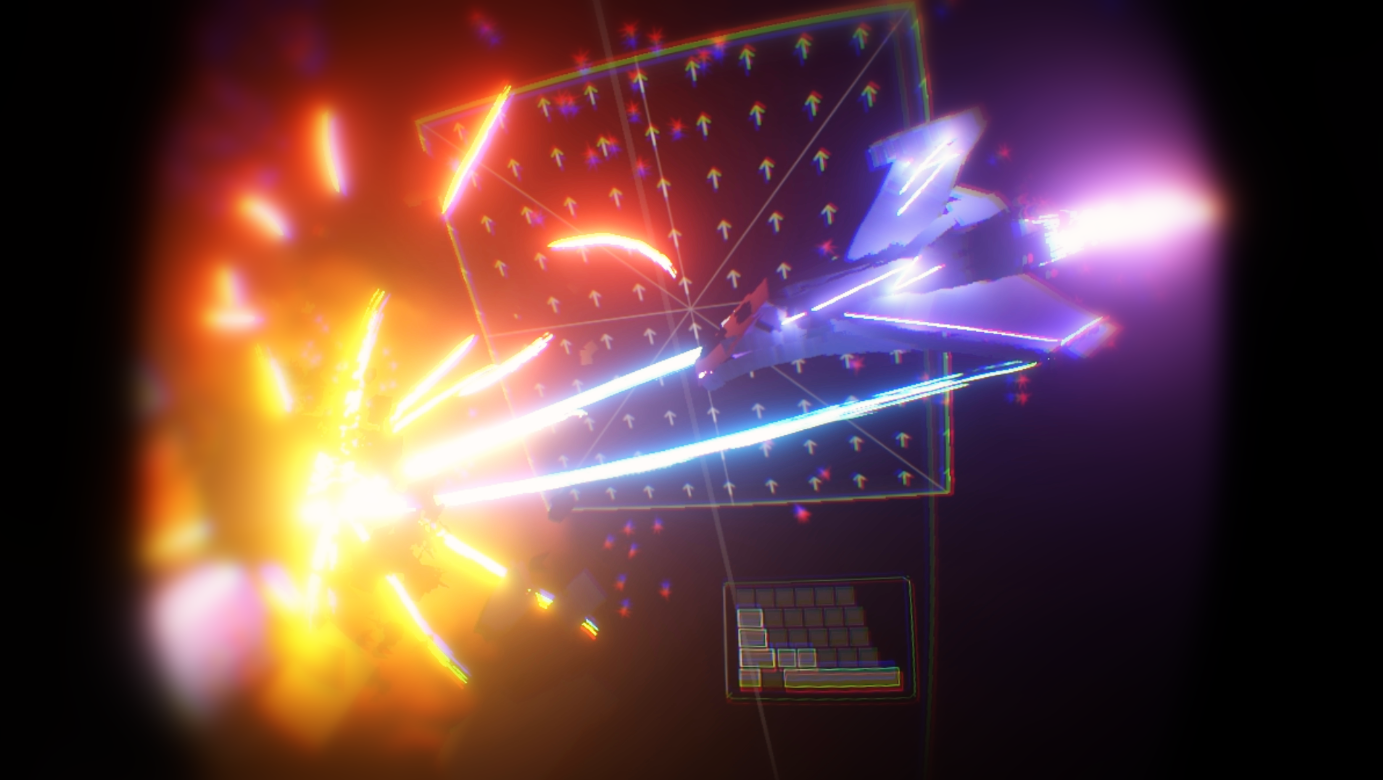

That degree of precision came into its own in the next demo, virtual painting app TiltBrush, by Skillman & Hackett. Rather than a flat virtual canvas in front of me, the entire space – featureless and black, with only the scant outlines of a cube around me to delineate the limits of where I could roam – was open to my cack-handed art.

Here, the VR controllers come into their own. My right hand had a "paintbrush", triggered using the forefinger button. In my left, meanwhile, the controller had sprouted a floating three-sided menu around its tip, like an oversized microphone flag. One side had brush types, colors, and an undo tool, switched between by physically turning my hand so that each face would be visible, and then selected by pointing the right controller at the tool or hue I wanted and clicking.

If you've ever done light painting, using long-exposure photos to capture a stream of light from a torch, then you'll be familiar with the Vive art app. The default brush left a long line of glowing light in the air in front of me, and soon I was sweeping lazy arcs of sinuous color around myself.

HTC told me later that some first-time Vive users need reminding that they can twist and turn in the virtual space, painting around themselves rather than as if facing an invisible easel, but perhaps I'd learned my lesson from earlier as it wasn't long before I was ducking and turning to build up a 3D construction, switching brushes to leave trails of stars and fire. In the consumer version, your 3D art will be savable and shareable; it's probably no great loss that my creation was lost as soon as the demo was over.

I'm no artist, but with Vive it quickly proved addictive. There's something about being able to inhabit the same space as what you're creating: reaching in-between the streamers of light before pulling the trigger, so that you can trail a complex pattern back through what you've already done, for instance, or sketching out a vague sphere and then standing up so that it surrounds your face as though you're in a Daft Punk video.

It also proved a reminder of just how immersive the environment could be, and how quickly you could come to believe it was real. While I was engrossed in painting I spotted out of the corner of my eye what I assumed was a fly. It took a second or two before I remembered that nothing I was seeing was accidental, and that the sprite wouldn't be there if it hadn't been programmed in.

Even when you rationally know that, however, it's easy for your instincts to get confused. Another demo jarringly loaded me standing in the middle of a tabletop game, Quar by Steel Wool Games, only the characters were busy fighting a tiny battle complete with guns and tanks. Crouching down, I was able to see it from their point of view; when I turned my head, just in time to see a cannon explode with a puff of smoke, I almost went to blow it away before remembering that it wasn't really there.

Valve's hand was most visible in the final demo, Aperture, starring the various characters from Portal. Taking place in a robot repair bay, I first had to lead in a malfunctioning 'bot (laughing at myself for trying to dodge the sparks shooting from its half-broken limbs) and then open it up, the internal components floating in the air in front of me. Reaching out, I could spin them around and manipulate them, using the VR controller as virtual tools.

While the most visually complex of anything I'd seen – it was frustrating not to have time to explore the detailed world around me – the final demo felt at times more like a movie I was standing inside than a game I was taking part in. For the most part, the things I actually interacted in were more akin to chapter points in a "choose your own adventure" book with only one route. Although animated incredibly, like when the floor and walls fell away and I took an instinctive half-step back onto a remaining ledge, it was more a skit you occupied than anything else.

The Future

The humor was tongue-in-cheek, but there are some practical implications. While the robot's components were obviously fictional, there's a lot to be said for the potential of exploring a huge, high-resolution exploded model: a car engine, perhaps, or animated instructions on how to repair a component in a server or some other complex equipment.

That's important, because the expectations for Vive go beyond gaming and movies. HTC is playing many of its cards close to its chest with the headset, but according to Jeff Gattis, executive director of HTC's Connected Products Group, this is only the start of the company's virtual reality journey.

This first headset will sit at the premium end of the scale, certainly, but Gattis tells me that HTC sees value across the scale, from geeky must-have Google Cardboard, through devices which use a docked smartphone as their display and processor such as Samsung's Gear VR, and up.

Similarly, Gattis is confident that a fully wireless version of Vive will happen eventually; unfortunately, he points out, the technology simply isn't up to scratch yet. Nonetheless, he agrees that gaming is likely to be the first area in which adoption will be seen, if only because it's a segment in which VR already has some mind-share. Other potential fields where Vive could have legs include travel, education, and even shopping.

So when can I try it?

Since words and even video can't do justice to the experience, HTC has a plan to bring Vive to the people. The company plans to take the headset on an international roadshow, Gattis told me, turning up with VR in hand at gaming conventions and other locations so that people can try it out for themselves.

That'll kick off in the Spring, which is when the developer edition of the headset is expected to ship. The consumer edition, meanwhile, will follow on before the end of the year, pricing yet to be finalized.

It's still very early to reach anything but the broadest conclusion about Vive. It's certainly fair to say that my relatively brief time with the VR headset left me both impressed and wanting more: I could've easily spent far longer testing the possibilities and limits of the art app, for instance, and though I'm not much of a gamer, I could see the immersive nature of Vive drawing me in, especially in titles where exploring carefully-crafted worlds is central to the game.

Although the common perception of virtual reality is dropping a player into a digital warzone, the degree to which I was engrossed by the 3D tabletop game – even without being able to manipulate the figures myself – and entertained by Job Simulator suggests there's far more to the technology than just first-person shooters.

Wrap-Up

Cynical it may sound, but if HTC were going it alone with Vive I would be pessimistic about its success. Sure, it's capable hardware and the visual quality – even of a prototype – was impressive, but if there's one thing HTC's experiences in phones over the past couple of years has proved, it's that it takes more than great devices to be successful.

With Valve onboard, however, the outlook seems a whole lot brighter. HTC makes great tech; Valve has a recognized brand and a reputation among games developers. The huge Facebook acquisition of Oculus, not to mention the subsequent reveals of Sony's Project Morpheus and Microsoft's HoloLens, is evidence that VR is shaping up to be a key trend in entertainment, particularly as display and tracking technology finally reach a point where the experience is neither grainy nor nauseating.

Still to come are details of pricing, what titles will be offered at launch, and what other hardware will need to be paired with Vive, all key contributing factors in the breadth of its adoption. There's also the question of how well it will work in a space smaller than the default.

Nonetheless, HTC gets something right straight out of the gate: Vive has a wow factor even in a world where virtual reality is no longer a pipe dream.