Anova Precision Cooker WiFi Review

Anova's first consumer sous-vide was a touchscreen-topped wand both credited with helping the fashionable cooking style broach a broader market and criticized for being a little confusing. The follow-up Precision Cooker Bluetooth dialed back the display to a couple of temperature read-outs, added a literal dial for local control, and threw in short-range wireless to link with your phone. Now there's the Precision Cooker WiFi.

Almost identical to its predecessor, it's 15-inches tall, made of plastic and stainless steel, and clamps to a pan, basin, or bucket with a neatly designed, adjustable mount. It'll open up wide enough to hook over the side of a polystyrene cooler box, for instance. The stainless steel section unscrews so that you can clean the inside, should that prove necessary.

Sous-vide might have a reputation for complexity, but it's actually pretty simple to get going. You stand the Precision Cooker in a pot of water – cold, or warm from the tap if you want to save time – dial in the required temperature, and hit the start button. It takes 5-10 minutes to heat up, a small impeller on the base moving the water around to keep things consistent.

While that's happening, you need to seal up your food. Easiest way is the so-called immersion route, where you put whatever's to be cooked into a ZipLoc bag or similar, dunk it into water slowly to drive the excess air out, and then seal it up just before the water gets to the top.

Alternatively you can buy a fancy vacuum sealer or, if you trust your market or butcher's packaging to be BPA-free, simply dunk a pre-sealed bag right in. I found a couple of small bulldog clips helped to keep the bags from moving around in the flow of water and potentially blocking the impeller outlet.

Seldom one to tackle meat with reserve, I acquired two slabs of New York steak, each roughly 2-inches thick. Using the immersion method, a Ziplock bag for each salted and peppered piece, they dropped into the 130 degree water for about an hour, emerging gray and uninspiring.

After a sear in foaming butter in a pan on the stove, however, to give that Maillard reaction browning and characteristic caramelized points we love from steak, I couldn't wait much longer and hacked one open right down the center.

The joy of sous-vide, I'd been told on several occasions and by multiple enthusiasts, is that it cooks consistently. If you want a thick steak with a medium-rare center and cook it the usual way, then by the time the middle is as you like it, the areas closer to the edge are over-cooked.

Yes, you can juggle the timing and rest period afterwards, pulling the steak off the grill a little early and counting on the exterior heat to finish bringing the interior up to temperature, but it requires a deft touch and that's not something I'm commonly credited with.

Sous-vide bypasses all those calculations, counting instead on evenly raising the whole item up to the same consistent temperature. It takes a little longer than cooking on a stove or a grill, yes, but that time is spent in a more controlled way.

Hence the incredibly rich, meaty, almost-bizarrely consistent in its done-ness piece of beef that I enjoyed, singing the praises of Anova and sous-vide in general along the way.

Heady with success, I ran straight to the butchers and then headlong into failure.

Maybe it's because I'm British, perhaps I'm just obstinate, but some of my favorite cuts of meat are the ones others would throw away. If steak was good, I decided, then beef cheeks would have to be even better – after all, they're basically designed to be cooked low and slow.

Indeed, sous-vide has a lot in common with braising, which is how you traditionally take something like a beef cheek – tough, initially, from all that hard work in the fields, but striated with collagen that breaks down during prolonged cooking and makes for a rich, unctuous sauce – and turn it into a hunk of fork-tender, flavorful, and oddly-affordable goodness.

Unfortunately what it actually did was highlight the potential drawback of sous-vide: even with WiFi monitoring, and sub-degree temperature accuracy, you might not know that dinner is a wash-out until two days later, when you're getting ready to actually eat.

The beef cheeks sat in a baggie of red wine and homemade stock for two days at 145 degrees – as per a well-praised recipe I found online – and came out tough and undercooked. Further reading suggested I might have got better results at something more like 178 degrees. Life lesson? Don't try a new sous-vide recipe for the first time if you have someone to impress, since there's every chance that you might need to tinker before you get it to your taste (or, indeed, until it's just plain edible).

Since then, I've pushed the needle back into palatable with some juicy, ethereally tender pork porterhouse steaks, and marveled at how evenly-cooked fish is now a doddle. Sous-vide's reputation for prolonged cook times isn't always deserved, either, since you can have a steak ready in an hour or so, while a filet of fish takes even less.

So far, so sous-vide good, but do the Anova's extra bells and whistles play a useful tune in the kitchen?

The previous Precision Cooker had Bluetooth, which allows Anova's excellent control and cookbook app to link up wirelessly. From there, you can browse recipes, tailor them depending on your portion size and factors like how well-done you like your meat, and then your iOS or Android phone automagically sets the temperature and the timer.

With the new Precision Cooker WiFi, you still get Bluetooth and compatibility with the old app, but now the wand will play nicely with your router, too. Pairing – which took a few failed attempts, eventually requiring that I completely shut off Bluetooth on my iPhone and then turn it back on again before the Anova app could see the cooker – sees you pick your WiFi network of choice, teach the Precision Cooker its password, and after that point it will automatically get online whenever it's powered on.

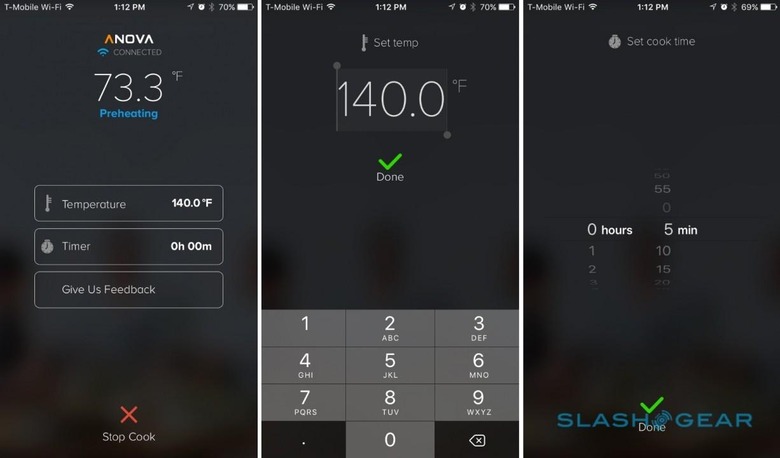

Unfortunately the WiFi app is a poor shadow of its Bluetooth-centric sibling. In fact, it's little more than a monitoring tool: you can set temperature and a timer (the latter doesn't actually power off the cooker, just remind you when the preset time is up) as well as turn the unit on and off.

Anova's boast is that you can do that from anywhere, whether you're elsewhere in the house or still at the office. Leaving aside how advisable it is to leave raw food in a pot of tepid water all day – the Precision Cooker can't refrigerate, only heat, unlike for instance the Mellow sous-vide set to launch in 2016 – there's a shortage of even the basic features.

Over Bluetooth, for instance, the first Anova app will warn you if water levels are low: that's important, since during prolonged cook times the warm water evaporates, and you need a certain minimum amount in order to cook properly. Unfortunately, the WiFi app lacks that notification. There are no recipes, either.

Eventually, Anova says, the apps should be harmonized and you won't have to use both for the full experience, but for the moment it feels like WiFi has plenty of IoT potential but that's still something to be built out with future app and firmware updates.

I'm happy enough with the core functionality to consider the $199 Anova asks for the Precision Cooker WiFi reasonable. After all, not that long ago you'd be looking at ten times such a figure – if not more – to get started with sous-vide.

Still, with Nomiku's WiFi-enabled cooker on the near horizon, Anova doesn't have long if it wants to cement its first-to-market advantage. Existing owners of the Bluetooth model probably shouldn't feel the pressing need to upgrade, but this is a solid place to get started with one of the more exciting things you can do in the kitchen.

MORE Anova