The World's First Nuclear Submarine And Its Incredible Trip To The North Pole

Between March 1869 and June 1870, Jules Verne published his now-famous science fiction story "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea." It tells the tale of a group of adventurers aboard a technologically advanced (for the time period) submarine controlled by the eccentric Captain Nemo.

The fictional vessel of Verne's story was powered electrically — something of a novelty at the time, the first electric streetlights wouldn't be installed for another eight years — allowing it to reach depths and explore environments never before seen. Verne called his vessel the Nautilus.

When the United States government decided to build a nuclear-powered submarine, it took inspiration from Verne's cutting-edge vessel, at least in the name. The USS Nautilus was the world's first nuclear-powered submarine, and it revolutionized the way we navigate the world's oceans, not to mention the way we conduct warfare. The Nautilus carried out a number of missions over the course of 25 years in the water, but it's most famous was an under-ice crossing of the North Pole, cutting a new path between the Pacific and Atlantic. Here's how that happened.

Hyman G. Rickover, the Father of the Nuclear Navy

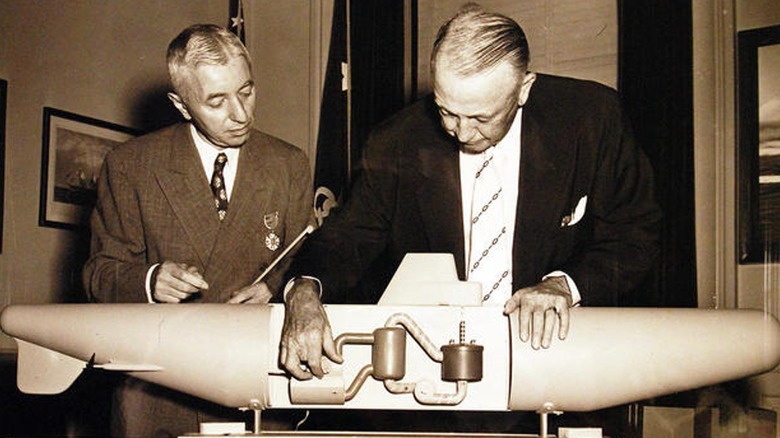

Hyman Rickover was born in Poland and moved to the United States with his family as a child. After high school, unable to afford college tuition, he joined the Navy. Rickover proved ambitious and capable, climbing the ranks swiftly. By 1946, he was assigned to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Often called the Atomic City, Oak Ridge was intentionally built to support the Manhattan Project and, more broadly, nuclear research. Once World War II ended, control of the city was transferred from the United States government to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Rickover's job at Oak Ridge was to develop a nuclear energy plant, but he became enamored with the idea of a nuclear-powered submarine.

With the backing of the Chief of Naval Operations, Rickover became Director of the Nuclear Power Division, Bureau of Ships as well as chief of the Reactor Development Division of the Naval Reactor Branch at the AEC. From there, he led the charge for the development and construction of Nautilus and a class of nuclear submarines that followed.

Developing the Submarine Thermal Reactor (STR)

The Nautilus was powered by a Submarine Thermal Reactor (STR) which utilized a pressurized water reactor. Before the development of the Nautilus, no such reactor existed, and they had to be invented for the project. Today, pressurized water reactors are the most common nuclear reactors in the world. You can find them in dozens of nuclear-powered submarines as well as land-based nuclear power plants.

The reactor technology for the Nautilus was developed by the Bettis Atomic Power Laboratory, under the umbrella of the Westinghouse Electric Corporation. It worked by feeding pressurized water into the reactor core. There, it came into contact with the fissionable fuel source, typically uranium. As heavy elements split into lighter ones, they shed electrons and neutrons into the water, heating it. The heated water was then fed into another chamber, where it was released in the form of steam, spinning a turbine.

This reactor design had benefits over existing submarines because it doesn't require the introduction of air into the engine and needs only a small amount of nuclear fuel to operate. Combined, that meant the crew could operate more quietly and for extended periods between surfacing.

The Nautilus

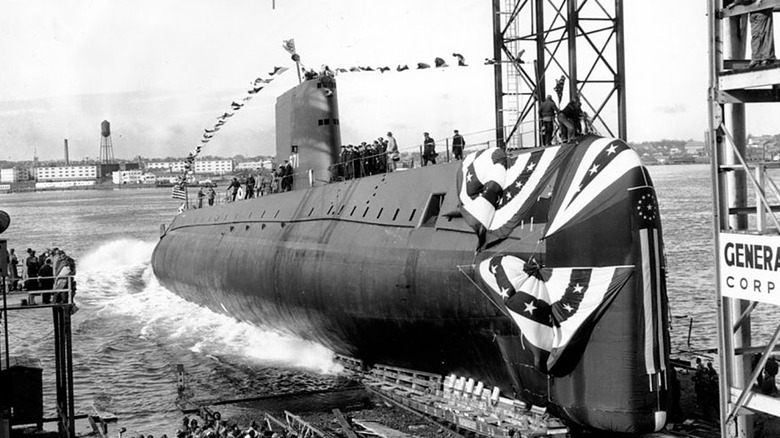

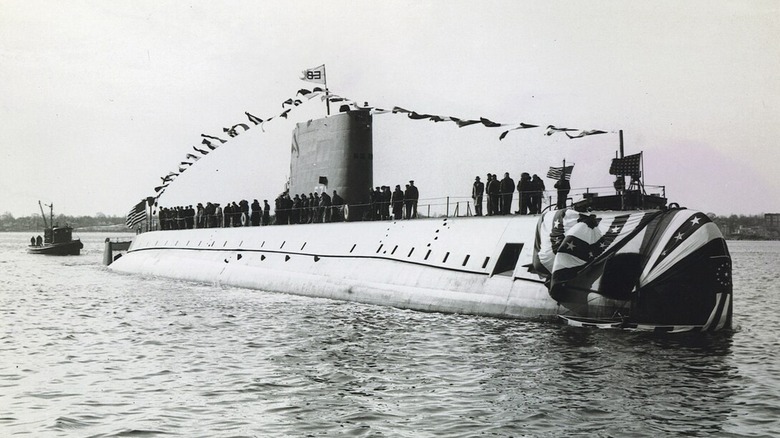

Construction of the history-changing submarine was authorized in 1951 and began in the summer of the following year. Construction continued for roughly two years before it was completed. Then, on January 21, 1954, the ship was launched into the Thames River in Connecticut. Mamie Eisenhower was there, in her duty as First Lady, and she broke a ceremonial bottle of champagne on the hull.

Once finished, the ship came in at 319 feet long, 21.5 feet tall, and it displaced more than 3,000 tons of water when fully submerged. Owing to its nuclear fuel source, it spent most of its time in service submerged, rising to the surface only when necessary or between missions. When in motion, Nautilus could dive as far as 700 feet below the surface of the ocean and cruise in excess of 20 knots, roughly equivalent to 37 kilometers per hour (23 miles per hour).

Prior to the Nautilus, the world's most advanced submarines could stay underwater for a day or two at most. That was the gold standard and the time to beat. Nautilus smashed those limitations, regularly staying down for weeks or months at a stretch. Even now, more than half a century later, she remains an impressive ship.

Underway on nuclear power

While the ship officially launched on January 21, 1954, it didn't really get underway for almost another year. It remained tethered in port until January 17, 1955, when the Nautilus' first commander, Eugene P. Wilkinson set her off with a simple radio message, "underway on nuclear power."

While the ship was technically operating under its own power, it remained in port for several months while the crew finished running tests and kicking the proverbial tires. Then, finally, on May 10, 1955, Nautilus made for the ocean for the first time. Its shakedown cruise took it from Naval Submarine Base New London in Connecticut to San Juan, Puerto Rico.

They made the trip of roughly 1,400 nautical miles in 89.8 hours, submerged the entire way. At the time, it was the longest trip a submarine had ever made while submerged. It was also the fastest speed a submarine had ever maintained for more than an hour at a time. With the first journey in the history books, the Nautilus spent the next couple of years traveling the world's oceans, performing tests and exercises, and visiting various naval bases and ports. Basically, doing the submarine equivalent of the red carpet tour circuit.

The Sputnik Crisis

October is always spooky season, but October of 1957 was particularly scary because there was a new unknown in the world. Or, more accurately, there was a new unknown orbiting the world. On October 4, 1957, the world was rocked by the successful launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik.

The small machine, only a few feet on a side, was a huge technological achievement, the world's first artificial satellite to successfully reach orbit. It would eventually lead to the space race, satellite communications, GPS, and more, but nobody knew that at the time. Instead, when Sputnik started circling the globe a whole bunch of people lost their cool really quickly.

Suddenly, the Soviets had a high-tech gadget whizzing over our heads at high speeds. Moreover, it was operating at an altitude that no one had ever been to before. Whatever they were planning to do with their satellite, there probably wasn't much we could have done about it. This is why some folks were concerned that the Soviet Union might use its newfound technological capabilities to drop bombs on us from above. Just a decade earlier, the United States had used its own technological superiority to develop and use nuclear weapons. It wasn't keen to be on the other side of that equation.

Voyage to the North Pole

While Sputnik turned out to not be a bomb-dropping satellite, it caused a considerable uproar at the time of launch. So much so that then U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the Nautilus to cross the North Pole, under the arctic ice. The crossing was, in part, a demonstration of the United States' technological capabilities in the water, and a show of power in advance of the looming submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) program. In short, the Soviets did a trick, so the U.S. needed to do one, too.

In the summer of 1958, Nautilus was hanging out on the west coast of the United States, stopping at ports in California and Oregon before heading north. On June 9, Nautilus left her port in Washington state for the first-ever journey beneath the north pole.

The mission, known privately as "Operation Sunshine," was a complete secret, only revealed after a successful crossing. That was intentional because the point was to show that the Nautilus was capable of such a journey undetected. It had the added benefit of allowing the crew to make a couple of missteps along the way, without being scrutinized.

Turning back

The crew of the Nautilus left for the open ocean on June 9, 1958, with the intention of becoming the first submarine to travel from the Pacific to the Atlantic, by way of an under-ice north pole crossing. While crossing the planet's north pole presents a number of unique challenges, the setbacks began almost as soon as the ship left port.

They made it only as far as the Chukchi Sea, between Alaska and modern-day Russia. There, shallow waters cover an ancient land bridge across the Bering Strait. When the Nautilus entered these waters, they were filled with a gnashing collection of sea ice, too thick for them to safely sail through.

Instead, the Nautilus turned south, headed for the furthest thing from the north pole: Hawaii's Pearl Harbor. The crew put up its feet for a few weeks among Hawaii's tropical climes, waiting for sea ice conditions to improve, before setting out again. Considering the challenge ahead of them, it's only fair that the crew got a brief island vacation in advance.

To the North Pole again

By late July, sea ice conditions had improved, and the Nautilus set out for the Arctic again on July 23, 1958. This time, the crew was determined to make it. It cut a path up the Pacific, from Pearl Harbor to the Bering Strait and the Chukchi Sea. While ice conditions were better, crossing the strait is no easy task.

The strait averages only about 100 feet deep for most of its length and some of the remaining sea ice extended up to 60 feet beneath the surface. To make the passage, the Nautilus had to squeeze between ever-drifting canyons made of floating icebergs and the sea floor. Once beyond the strait, Nautilus continued northward and reached the geographical north pole on August 3, 1958. The ship didn't surface at the pole. Instead, it traveled another 1,600 nautical miles and surfaced off the coast of Greenland a few days later.

When Eisenhower later spoke about the crossing, he suggested that the newly pioneered route between the Pacific and the Atlantic might one day be used for trade, though the potential wartime applications were more apparent. The crossing accomplished its goal and the ship's captain William R. Anderson was awarded the Legion of Merit, while the ship's crew received the Presidential Unit Citation for the heroic effort.

The Sperry gyro compass

Central to the success of the trip was the navigational equipment aboard. At the planet's magnetic poles, conventional navigational equipment goes haywire, being unable to rely on the Earth's magnetic field for orientation. There was some concern that the Nautilus might become lost at the north pole, but the crew was confident the instruments would prevail.

For most of their journey, the crew of the Nautilus relied on dead reckoning, the process of orienting yourself via landmarks as well as speed and direction estimates, and used that in the crossing as well, particularly at the pole when the instruments were less reliable. Still, the crew didn't have to rely on dead reckoning for much of the trip, thanks to the Sperry compasses onboard. The Nautilus had a Sperry MK 19, which had previously been used to travel to latitudes of 86 and 87 degrees north, with good performance. The Sperry gyro compass is capable of seeking north while also providing directional information to find its position.

The crew used the compass, which remained true until between 88 and 89 degrees north, then used dead reckoning to make the crossing. Once they were 17 miles beyond the pole, the sailors shut down the Sperry, flipped it 180 degrees, and turned it back on. Along the way, they checked the MK 19's performance against two other Sperry instruments, an MK 23 and a Sperry Gyrosyn. The instruments remained in agreement throughout, providing added confidence in the ship's navigation.

Nautilus decommissioned

After 26 years in service, the Nautilus was decommissioned on March 3, 1980, in part because it had developed a shimmy. When traveling above about 4 knots (7.4 kilometers per hour or 4.6 miles per hour), the ship would vibrate, making it potentially more detectable by radar. That's not exactly a quality you want in your stealthy nuclear submarine.

During its tenure, the Nautilus sailed nearly half a million miles all over the world, earning it a designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1982. Four years later, in 1986, the Nautilus went on display at the Submarine Force Museum in Connecticut, not far from where it was built a few decades earlier. It has been there ever since, with a few exceptions.

The ship was closed to the public in 2021 for renovations, some of which reconfigured the ship to make it safer for civilian visitors, and re-opened to guests in August 2022. At the time of this writing, the Nautilus is perched in Connecticut's Thames River, just outside the Submarine Force Museum.