Windows 8: what Microsoft did right and what went wrong

Windows 10 is coming really soon. If AMD is to be believed, that is happening around July. Given this upcoming version of Windows is set to fix a number of complaints about Windows 8, it's release will surely call to mind some its predecessor's shortcomings. But for all the warts that Windows 8 had, it wasn't completely a failure in all aspects and even laid the foundations of many features and mindsets still present in Windows 10 and elsewhere. Here we take a look at 5 of the things Windows 8 could have gotten right and also how they failed to reach the mark.

1. Content is king, chrome is cruft.

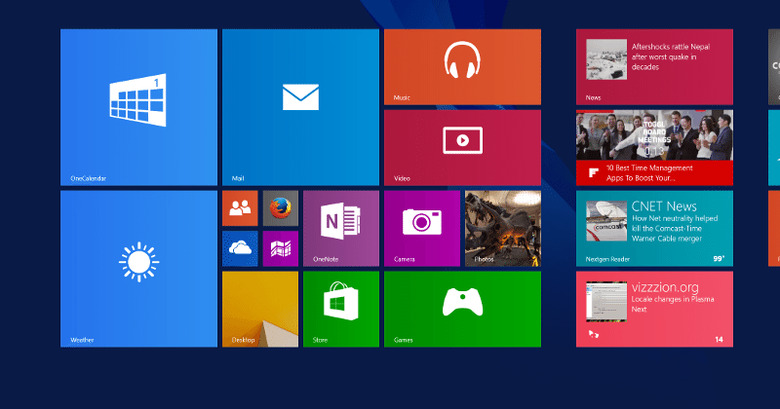

Perhaps one of the best things about Windows 8 Store apps, a.k.a. Metro apps a.k.a. Modern apps (Microsoft really needs to pin down what these apps will be called) is that they put content front and center and everything else out of sight. This is in stark contrast to regular desktop software, especially those from Microsoft, where the user interface, also called the chrome, took up a large portion of your screen space. The highly contentious Ribbon interface introduced in Microsoft Office 2007 tried to rearrange the clutter, but the clutter was still there and took up as much precious vertical space.

With Windows Store apps, the UI is shoved out of the view entirely by default. They're still there, though substantially fewer in number and hidden, summoned by swiping gestures from the top or bottom borders of a tablet or a right-click for those with a mouse. Mobile device users, particular those on Android, might be now familiar with this convention which is being called "Immersive Mode". It's particularly applied to video players, book readers, and games but Microsoft uses it for everything by default.

Where it failed: Discoverability and consistency. Sadly, execution wasn't exactly well thought out and the transition from visible menus to hidden ones was jarring for many. "Out of sight, out of mind" also meant people presumed they were not there at all. Swiping from edges wasn't exactly second nature, and many took a long time to get used to it. And even when they did, the whole pattern wasn't inherently consistent. Some apps made use of the top edge, some used the bottom. Others used both. There didn't seem to be any coherent guideline where to find which option. Then there's the universal Charms menu, which is going away soon, which brought its own set of hidden controls to confound even more seasoned Windows users.

2. Focus on typography, design

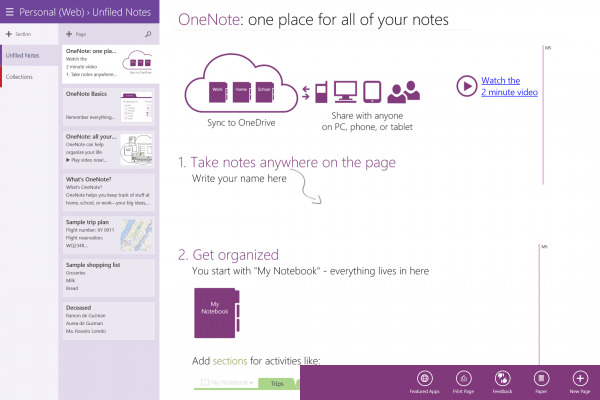

With content front and center, Microsoft really had no choice but to try and make everything visually presentable. Regular desktops apps were, and still are, utilitarian at best, a jumbled visual mess at worst. Microsoft started its design journey with Windows Phone 7, introducing the Metro, later Modern, design language, one that made judicious use of text and very minimal visual clutter. The visual aesthetic that arrived on Windows 8 cemented the flat, minimalistic movement that has been growing in corners of the Web. We would later see that same direction in Android and eventually iOS, a platform that was once the shining example of skeumorphism.

Flat and minimal meant that the user's attention wasn't inordinately lavished on buttons and controls. It meant that the user interface simply presented a way to let users do what they want and then get out of the way. But that didn't mean they have to be boring or dead, and the proper mix of fonts, icons, and animations could successfully bring such a user interface to life.

Where it failed: Usability. The goal for crisp and clean user interfaces might be laudable, but everything in extremes eventually end up being bad. Of the three major platforms, Windows and Windows Phone are perhaps the most minimalist of them and exhibit some of the usability pitfalls of flat minimalism that even iOS and Android suffer from. There is very little in the way of icons and bounding boxes and sometimes things visually bleed into one another. A piece of text can either be an informational label or the equivalent of a button, and at time there is very little to distinguish between the two. Conversely, some apps would use icons without text labels, leaving users to guess what a certain icon would do or try it out for themselves and find out too late it was not what they thought it was. To be fair, Microsoft's own apps espoused putting text beneath icons, but the lack of consistency once again rears its ugly head.

3. Daring to blend Touch and Desktop together

Microsoft made a rather bold gambit, one that was probably driven as much by business than it was by innovation. Microsoft was, and mostly still is, a desktop software company. But it could no longer ignore the tide of mobile. At the same time, however, it couldn't simply jump ship, leaving its bread and butter source of income. And so it tried to seek a middle way, to some extent. That gave birth to the duality of Windows 8 embodied in the Surface Pro devices, and, honestly speaking, it wasn't all that bad. At least on paper.

Mobile advocates might chide Windows 8 for still adhering to the old desktop ways even on a tablet. In Apple's line of thinking, mobile devices are primarily content consumption devices. But look at some of the most popular apps today and you'll see a good number of them are actually for creating content, from editing photos, to composing music, to stitching up videos, to making art. People are starting to do the activities they do on regular computers, just with different, and sometimes more streamlined, interfaces and more constrained resources. If you had a device that was capable of being both a regular computer as well as a mobile device, wouldn't you bite as well?

Where it failed: Windows RT and schizophrenia. That dream, however, falls apart when faced with the red-headed stepchild that is Windows RT. WinRT was poised to be the iOS and Android of Windows, a version of the operating system that was designed to be totally for mobile, for touch, and for content consumption. In theory, that could have worked, but in practice, the dearth of apps and the confusion that followed practically signed its death sentence. It boggled users why an OS that looked like Windows 8 could not run regular desktop apps just like Windows 8. Other than a different CPU architecture (ARM vs x86/x64), the distinction felt arbitrary.

And we cannot ignore the fact that majority of those using Windows were still using it on the desktop. The touch-based, tablet-oriented Windows Store apps didn't make much sense in their keyboard and mouse world and the disjunct between the two was jarring and disconcerting.

Windows 10 promises to fix these concerns, but it is no silver bullet. In one case, it might actually still end up repeating one of these mistakes.

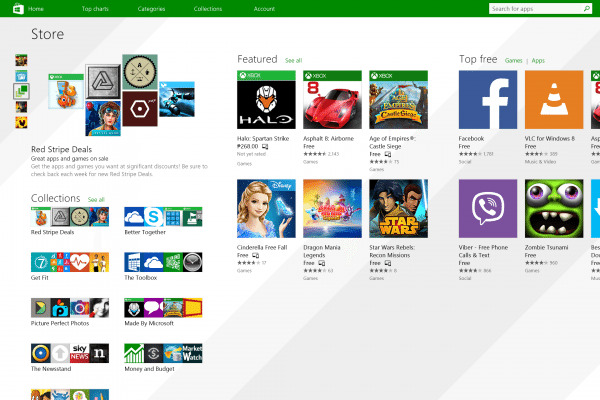

4. Windows Store

Windows is notorious for its selection of malware at ever nook and cranny. One wrong download and your system is compromised. Mobile platforms have set up a first line of defense by establishing app repositories for, more or less, sanctioned software. Although Windows 8 still supports the old ways of installing software, which is well and good for many, it also introduced the concept of a curated selection of apps deemed safe, though not exactly always worthy.

For those who are not always sure where to best get their software, the Windows Store should be their first stop. The Store now shows not only "Modern UI" apps but even those designed for a regular desktop, with a link to the correct website in order to avoid phishing scams. This last part is particularly important. It might be a bit of a pain for developers and publishers to get their names and apps on the Store, but it at least makes it safer for their users, which should be their concern as well.

Of course, there is no stopping users from going directly the website or third party sources to get their apps. And there's nothing wrong with that, if they know what they're doing and are prepared for the consequences. For those who don't or who are interested in seeing what's in store (no pun intended), the Windows Store, like any other app store or repository, is a great idea.

Where it failed: App selection. An app store, however, is only as good as the apps stored within. And this is where the promise of Windows 8 and Windows RT ultimately failed. There was just not enough high quality, well-known apps to begin with. Windows Phone also shares in this plight. It would take years for some of the most wanted mobile apps to have a native Modern UI version, and sometimes would even take that long to get updated. Without mobile apps and without desktop apps as well, Windows RT was doomed to fail.

5. Surface Pro (and Surface 3)

It's difficult to look back at the history of Windows 8 without mentioning the Surface line of tablet hybrids. They are, to some extent, Microsoft's reference devices for Windows 8, just as Google used Nexus to show off Android as it envision the platform. And cheesy marketing ads aside, the Surface, particularly the Surface Pros, really embodied the full potential of the operating system. It was a device that married the content consumption of tablets with the serious business of laptops. It had the Windows 8 Modern interfacer as well as the traditional desktop setup. Of course, it also shared in all the shortcomings of the OS mentioned above. But hardware-wise, the the Surface had a lot going for it. Unlike, say, an ASUS Transformer or a Lenovo Yoga, the Surface doesn't look like a broken half of a laptop and was a tablet in its own right. The lightweight keyboards served as an input device as well as a cover, without putting on too much bulk. And unlike tablets of the really mobile kind, it has a full USB port. The Surface Pen, once Wacom but now N-Trig, is also a selling point.

Where it failed: Growing pains. Microsoft definitely didn't get it right the first time, although the very first Surface Pro already showed promise and a clear vision. Executing on the vision, however, took three iterations to almost make it perfect. The Surface Pro 3 has been widely acclaimed to be the best one yet, and the new Surface 3 takes that success, shrinks it down, takes away the fan, and delivers and even more mobile experience. Rumors of the Surface Pro 4 seems to indicate that Microsoft has finally found a winning formula and is now just refining that a little bit.

Of course, we can't fail to mention the Surface and the Surface 2, the ones that bore the ill-fated Windows RT. We might, however, see their ghost in the very near future, whether you like it or not. And you probably don't.

Windows 10: Windows 8 done right?

A lot is hedging on Windows 10 right now, mostly because it is poised to correct the mistakes of its predecessor, just as Windows 7 addressed the failures of Windows Vista before it. And while things like Continuum and Universal Apps that run across the whole gamut of devices definitely sound promising, we still have to wait on the final product to be able to really say that this is it. That said, one point in particular seems worrying, hinting that, to some extent, Microsoft might be prone to repeating history.

Aside from a full Windows 10 and Windows 10 for phones, there will be a middle child between them. This will be called, for lack of a more formal name, Windows 10 for small tablets. To be precise, tablets that are smaller than 8 inches. Microsoft has already made it clear that these tablets won't be getting the Continuum experience. They won't be able to run regular desktop apps like their larger counterparts (This only applies to new tablets released after Windows 10. Small tablets upgrading from Windows 8.1 are safe). In a nutshell, they will be confined to using only apps from the Windows Store. Sounds familiar? Yes, it is Windows RT again, but this time, the distinction isn't based on processor but on tablet size. It does make more sense, considering you're unlikely to comfortably use a full desktop experience on a 7-inch tablet.

The success of this particular subset of Windows 10 will again depend on the apps that will be available in Windows Store. If the rather sorry state of that app store is any indication, it is unlikely to take off with flying colors. At BUILD 2015, Microsoft announced some new strategies to help alleviate that problem. Although it won't directly let Android and iOS apps run on Windows 10, Microsoft will be providing tools to let developers recompile their mobile apps to work on Windows 10 phones, but not exactly on other Windows 10 editions. Depending on the end product, this could just be a half step forward in the right direction. Windows 10 users still deserve native Windows 10 apps, especially ones that will work on desktops and tablets as well.

Microsoft also mentioned allowing win32 desktop apps inside the Windows Store but with a slight caveat. These programs will run in a sandboxed environment that will not make changes to the system registry, allowing for easy installation and removal of those apps. Again, this will depend on how the final implementation looks like and whether it will trip up users more than it would help them. But the increased security is again a step in the right direction.

Windows 10, indeed, seems to be doing things right, but it's no panacea just yet and a lot still hinges on whether Microsoft will be able to keep those promises it just made and how well it will be able to execute them.