Upside-down jellyfish-deployed venom bombs remind us nature is lit

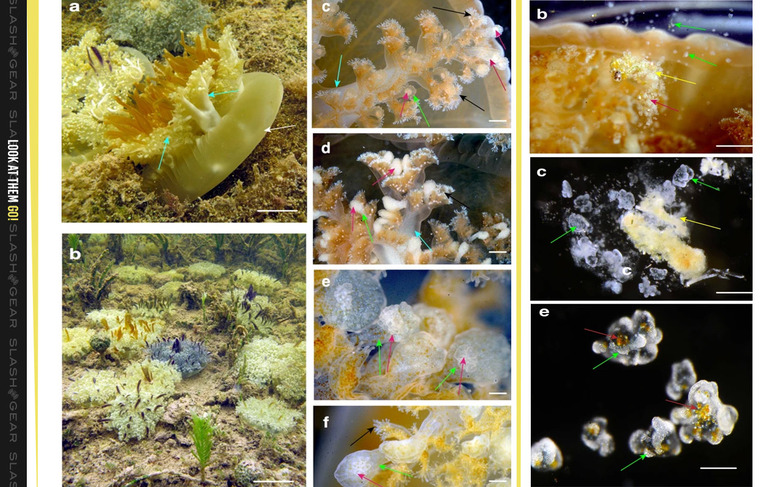

Cassiopea xamachana jellyfish sit on the floor of a body of water appearing like a fabulous bit of plant life from another world. Their appendages range from light white to dark hues of blue – they're beautiful, and might even seem harmless to the average passerby. But they've got a secret weapon – a projectile spore of sorts – made to shock nearby creatures like an invisible bomb.

The size of this Cassiopea jellyfish is up to 1 foot wide and 2 inches high – it's long and wide, really. It's not very tall. It's like a big fuzzy pancake – but far, far more dangerous to your health. This jellyfish lives in costal, tropical waters in the Indo-Pacific Ocean, along the coast of Southern Florida, Hawaii, and the Caribbean. NOTE: All imagery in this article is via the research paper linked below.

This creature uses its bell sort of like a suction cup to stay stuck to the floor of the sea. It's been known for some time that this jellyfish sits at the bottom of the sea upside-down to enable photosynthesis with symbiotic algae that live within its system. These tiny single-celled dinoflagellates, aka algae, aka zooxanthellae, turn energy from the sun into food for the jellyfish.

But what about the stinging water that seemed to surround each of these Cassiopea jellyfish when studied in the wild? "Snorkelers in mangrove forest waters inhabited by the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana report discomfort due to a sensation known as stinging water, the cause of which is unknown," said Cheryl L. Ames et. al. in the abstract of this newly-released study.

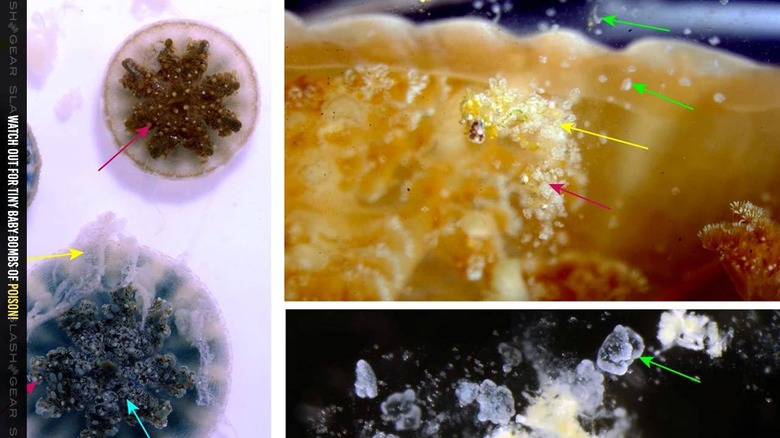

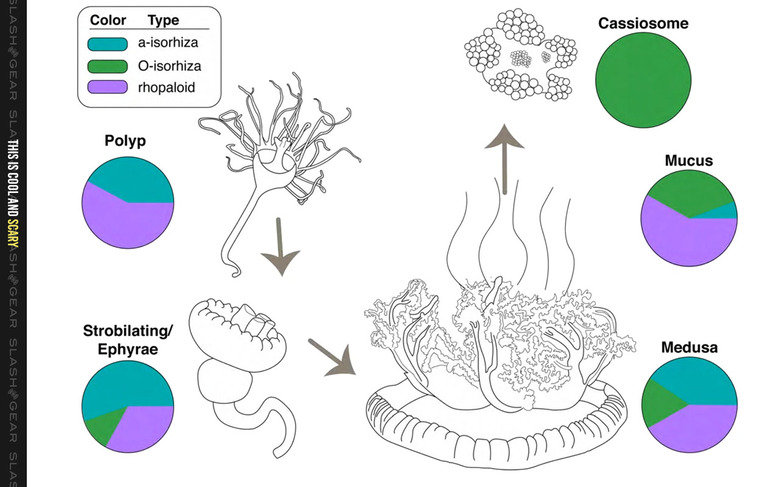

"Using a combination of histology, microscopy, microfluidics, videography, molecular biology, and mass spectrometry-based proteomics, we describe C. xamachana stinging-cell structures that we term cassiosomes." Basically these jellyfish are blasting mucus from their masses that distribute stinging poison bombs of venom.

The "cassiosomes" are made of two layers – the epithelial later is made mostly of nematocytes. The internal core is "filled by endosymbiotic dinoflagellates hosted within amoebocytes and presumptive mesoglea."

Cassiopea stings, said the study, are not particularly harmful to humans in small amounts. These jellyfish were "observed releasing copious amounts of mucus into the water when surrounding water was disturbed" during the study.

They saw distribution when jellyfish aquarists or snorkelers were detected, or when "pre items" were provided. One example of prey items included: Artemia nauplii in aquarium-reared medusae. And for those of you wondering: This isn't like octopus (or any cephalopod) ink – it's far less opaque and a whole lot more painful.

For more information on these wild creatures and their mucus-carried venom-bombs, see the research paper "Cassiosomes are stinging-cell structures in the mucus of the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana". This paper was published with code DOI: 10.1038/s42003-020-0777-8 on February 13, 2020, by authors Cheryl L. Ames, Anna M. L. Klompen, Krishna Badhiwala, et. al. and can be found in Nature: Communications Biology volume 3, Article number: 67 (2020).