This ethereal Starshade could revolutionize NASA's hunt for exoplanets

Find distant Earth-like planets capable of supporting life is going to take more than strong telescopes, with one NASA project exploring how a space umbrella and some super-skillful flying could lead to a science breakthrough. So far, missions like NASA's Kepler have identified thousands of exoplanets in the so-called habitable zone around a star where conditions conducive to life might be found.

That could just be a fraction of what's out there, scientists theorize, however, with more potential candidates right under our noses – but invisible to our instruments. The problem researchers face isn't just one of making a sufficiently powerful telescope, but changing the very way we identify exoplanets.

Currently, it's a fairly low-tech principle to which high-tech gadgetry is applied. One of the most common is transit photometry, which looks for signs of a distant star's light dimming as a planet moves in front of it. That – along with other methods, like Doppler spectroscopy – only really work for exoplanets relatively close to their star.

If we want to get more creative, a team of NASA engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California suggest, we need to not only boost our vision in space in some areas, but obscure it in others. Part of the NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program (ExEP) is looking at how a starshade might improve things, by effectively blocking out brighter light that could overwhelm sensitive instruments.

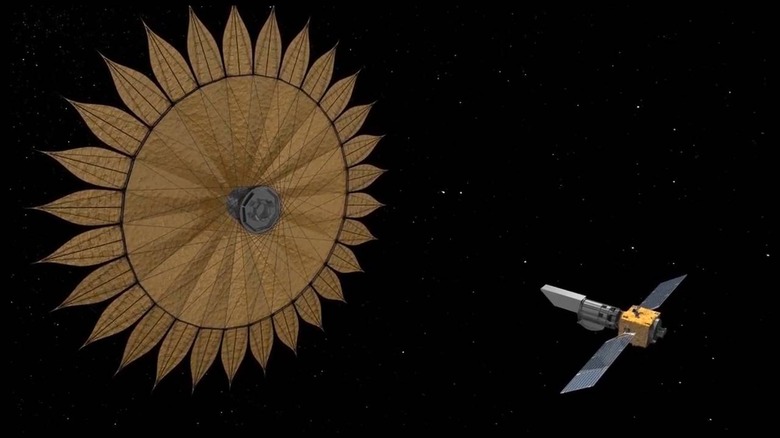

As the ExEP team envisions it, two spacecraft would be deployed and act in harmony. The first would have a telescope, casting its gaze out to identify planets beyond our solar system. The second, meanwhile, would fly ahead of the first. It would have a huge, flowering sunshade which would unfurl.

By using the starshade like a parasol to block out the brighter star light, the telescope could be far more useful. However it would also demand some highly precise positioning.

For a space telescope with a roughly 8 foot diameter primary mirror – like the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) that NASA plans to launch midway through the next decade – you'd need a starshade around 85 feet in diameter. It would need to be located between 12,500 and 25,000 miles from the telescope itself.

At that range, the starshade would need to keep aligned to within around three feet from its paired telescope. Otherwise, light could bypass its edges and overwhelm the fainter exoplanets such a mission would be tasked to locate.

The good news is that NASA's ExEP team believes such a precision flight would be possible. It relies on autonomous position corrections, being made in response to the shadow of the starshade making tiny shifts on the front of the telescope. Algorithms based on those shadow observations could keep the two locked into alignment for days at a time, and even support much larger starshades at greater distances. Indeed, gaps of up to 46,000 miles could be feasible.

Right now, NASA doesn't have a starshade mission on the books. However, such an instrument could end up launching after WFIRST, deploying in the late 2020s assuming the funding is there.