The problem with patents in tech

Patents are everywhere, and of course not just in the US, but there are particular industries where they show up more often than not. In our not so small corner of the world, we see dozens of patents on interesting technologies and potential products. Emphasis on "potential" because most of the time, they never come to be. Sometimes not from the party that filed the patent. More often than not, patents only surface when media get whiff of them or when used in a lawsuit. Because while patents were initially conceived to foster innovation, they run the risk of suffocating that very same thing instead.

The case of the sliding camera

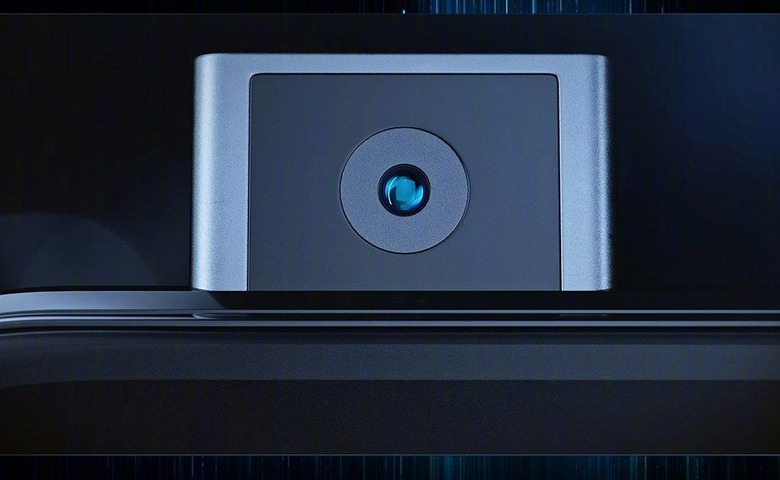

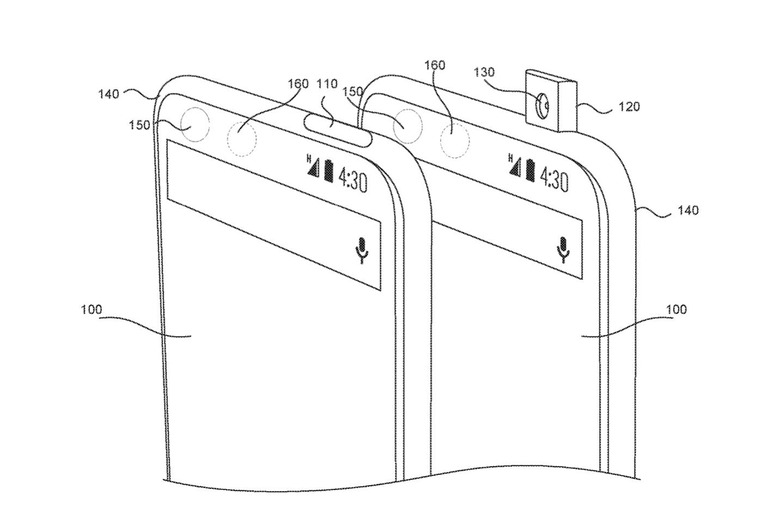

Last week at MWC 2018, Vivo announced not a new phone but a concept phone, one that barely had any bezels. It wasn't just an idea but an actual working device that could be ready for mass production if Vivo wanted to do so. And one of the highlights of that concept phone was Vivo's solution for the problem of the front-facing camera: a camera that slides out from the top.

It was an alternative to the now inexplicably popular notch. Being one of the first to come with that notch design, Andy Rubin of Essential was naturally asked about it. Rubin practically dropped the mic by pointing to its patent for that exact same idea. In other words, for all the attention Vivo got from it, it wasn't exactly original.

For better or worse, Essential never used that patent and probably never will. It will sit in its patent portfolio, gathering dust, until someone decides it's worth paying the company a handsome sum to use that patent. There will probably be lawsuits or licensing agreements involved unless Vivo goes back to the drawing board. Because, sadly, that's what the patent system has become.

Letters Patents

There's still some discussion on where patents actually originated, with some tracing roots as far back as Ancient Greece. But we don't have to go that far since the modern patent system can actually be traced simply back to the medieval period. It supposedly came from the phrase "letter patents", which was a document that, like today's patents, granted someone exclusive rights, particular to an invention.

The difference back then was that these rights were granted in exchange for disclosing the invention to the public. The patent holder had exclusive rights to the invention but the emphasis was on putting it in public domain for the common good. In other words, the value of patents was in their utility, not simply in having the idea, especially one that may not exactly have a concrete product derived from it. Or at least not yet.

Design and Math

Over time, the patent system naturally grew to include more forms of "inventions". Two particular types of patents have been put under scrutiny these past years, in no small part thanks to high-profile patent lawsuits.

Design patents, known as industrial design rights in other territories, cover ornamental, that is, not utilitarian, aspects of an item. Some would argue that design sometimes carries a level of utility, like the ridges in a soda bottle for better grip, or the appearances of computer icons for better usability.

More contentious, however, is the case of software patents, applied on computer programs, libraries, and algorithms. Software has become a very critical commodity in this digital and Internet age, so they shouldn't be taken lightly or relegated to the realm of "theoretical". That said, many liken patenting software to patenting mathematical formulas, which does sound ridiculous to some extent.

Exclusive Property

But while patents have grown in scope, they have sadly devolved in purpose and use. As a form of intellectual property, patent systems today, especially in the US, place more emphasis on the "property" aspect. Legally, patents are not a "right to make", that is, to actually use the patent. It is, instead, a right to exclude others. To put it bluntly, a patent basically means "if I'm not going to use it, nobody will". That is, unless a licensing fee is paid.

In an ideal world, that licensing fee is a fair trade for use of an exclusive property and to compensate the time and effort poured on research and development. Presuming that is the case. In practice, it has become a useful weapon to scare competitors or make them yield some cash. Patent laws often don't require patent owners to actually use the patent, only that they prove either ownership or validity of the patent. And this has led to a still profitable business of simply holding patents and suing companies. The system that was created to benefit the common good by inspiring innovation and protecting inventors has become a tool to protect vested interests and stifle those who might even dare produce an actual, usable product, whether they knew about the patent or not.

Wrap-up

A few years ago, there was a large cry for reforming the US patent system due to some high-profile cases. That cry seems to have died out as companies decide to settle things behind closed doors instead. After all, it's far more profitable in the long term to preserve the status quo rather than fix a broken system.

Patents themselves aren't necessarily wrong in that they protect a person's property. Over the centuries, however, it seems that the "for the common good" part has been left out both in spirit and in the letter of the law. And in a patent-litigious society, we might never come to see a variety of new touch gestures, foldable devices, or even slide out cameras.