Study warns these common COVID-19 face masks aren't helping

A new study warns that one of the go-to types of face covering for those complying with mask-wearing rules may not, in fact, be sufficient to prevent the spread of COVID-19 infected droplets. Masks have become a contentious fact of life in recent months, as public health authorities increasingly mandate their wearing in an attempt to cut down on community spread of the coronavirus.

Indeed, the US FDA has recommended masks be worn by the general public for some time now, as has the World Health Organization. Many states require masks be worn in public settings, including when shopping or in churches. If masks were used consistently, experts say, we could significantly shorten the impact of the pandemic in America.

However guidance varies – and has been an evolving topic – as to which sort of masks may actually provide the best protection when it comes to limiting the spread of COVID-19. The goal is to reduce the transfer of the small droplets that are emitted as a fine spray when people speak. If they're carriers of the coronavirus, which can be the case even without clear symptoms being exhibited, that can be enough to transfer it to someone else.

Multiple types of face covering have proliferated as a result, though there's been comparatively little research into the relative efficacy of each type. A new proof of concept study by researchers at the Duke Department of Physics indicates some of the more common mask alternatives may not, in fact, be providing as much protection as wearers assume.

Top of the list were N95 masks without valves, though since those medical-grade masks are still in relatively short supply, it's recommended that they're saved for healthcare professionals in hospitals and similar settings. Surgical or polypropylene masks also performed well, the researchers concluded.

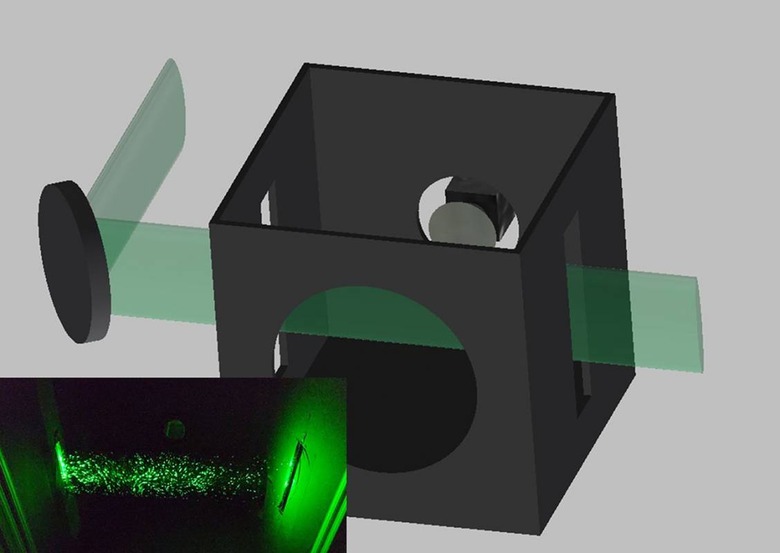

Cotton face coverings – including hand-made masks – "provided good coverage," it's reported, "eliminating a substantial amount of the spray from normal speech." That was measured by a wearer speaking in the direction of an expanded case beam inside a dark enclosure. A cellphone is used to record the results, and then an algorithm counts the droplets.

It's a simple setup – intentionally so, in fact – but it was enough to highlight a flaw with some of the more common face coverings being used. For example, "bandanas and neck fleeces such as balaclavas didn't block the droplets much at all," the team found. It calls into question how useful wearing a neck gaiter – that is worn around the neck, but which can be pulled up to cover the mouth when around other people – might actually be. Indeed, the stretchy fabrics used in such gaiters can actually break up larger particles, creating smaller particles that can be more readily spread.

It highlights the lack of clarity around things like which are the best fabrics to use for a mask, and whether wearing ill-protecting face coverings might actually lead to a dip in safety overall given people may think themselves to be less at risk. The WHO released guidance on the best sort of fabrics for non-medical masks, but actually figuring out how well a mask holds up in practice is something few would really know how to test.

That was one of the goals of the Duke researchers. The equipment they put together – including the box, laser, and optical components – are likely already in research labs, they point out, or could be bought new for under $200. Combined with a phone camera and the software, it would be a relatively straightforward way to assess the effectiveness of a type of mask.

"In this application, we do not attempt a comprehensive survey of all possible mask designs or a systematic study of all use cases," the team warns. "We merely demonstrated our method on a variety of commonly available masks and mask alternatives with one speaker, and a subset of these masks were tested with four speakers. Even from these limited demonstration studies, important general characteristics can be extracted by performing a relative comparison between different face masks and their transmission of droplets."

Still, if you're looking to choose a face covering, it looks like avoiding bandanas and neck gaiters might be a sensible approach until more research can be carried out.