Study details the lifestyles that may soften impact of inherited dementia

People who are at genetic risk for developing frontotemporal dementia (FTD) may be able to reduce the severity and progression of the disease by changing some lifestyle habits, according to a new study. Some people who have a genetic risk for developing this disease are all but guaranteed to develop it — despite that, researchers have found that people who kept both their minds and their bodies busy had far better outcomes than other patients.

The new study comes from the University of California, San Francisco, where researchers looked at the lifestyle differences between more than 100 people who had dominant genetic mutations that cause the disease, which usually starts manifesting in victims between the ages of 45 and 65 years. This type of dementia is known for causing a rapid decline in cognition typically leading to death within a decade.

Unfortunately, there are no treatments that can cure this disease or even put the brakes on it. However, the new study found that certain lifestyle factors are very effective at slowing down the disease's progression and reducing its severity, so much so that if it were possible to get these benefits from a pill, the researchers say they 'would be giving it to all our patients.'

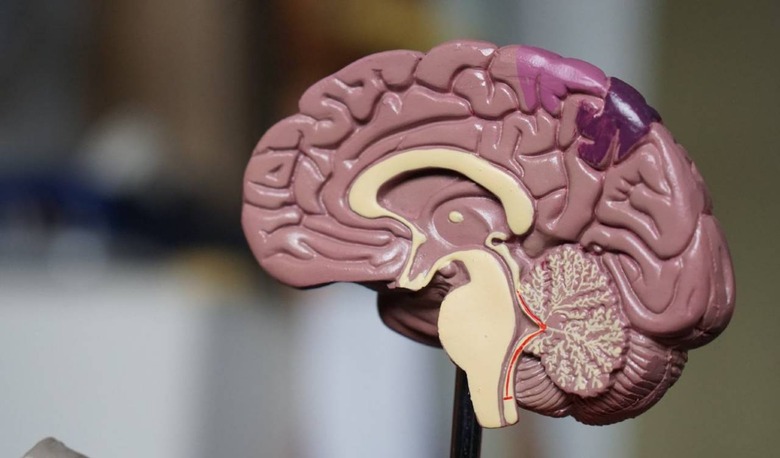

The study's participants were either in the early stage of the disease with only mild symptoms or they were asymptomatic. MRI scans were used to determine the degree of brain degeneration experienced by these participants as a result of dementia; they also took tests related to memory and thinking. Finally, the participants provided details on their daily physical activity like jogging and mental activity like reading.

It only took a couple of years into the study for the researchers to observe a noticeable difference in the severity and speed of the disease's progression in patients who had the least amount of physical and mental activity compared to those who had the highest amounts.

The 25-percent of participants who were most active had a 55-percent slower disease progression, according to the study, compared to the 5-percent of patients who were least active. Though the activity didn't stop brain degeneration, the active participants maintained better performance in comparison.

The researchers note that additional research is necessary to determine whether this link indicates that physical activity slows progression rather than something else, however. It is possible that the less active participants may have a more aggressive progression of the disease that influences their activity levels, for example.