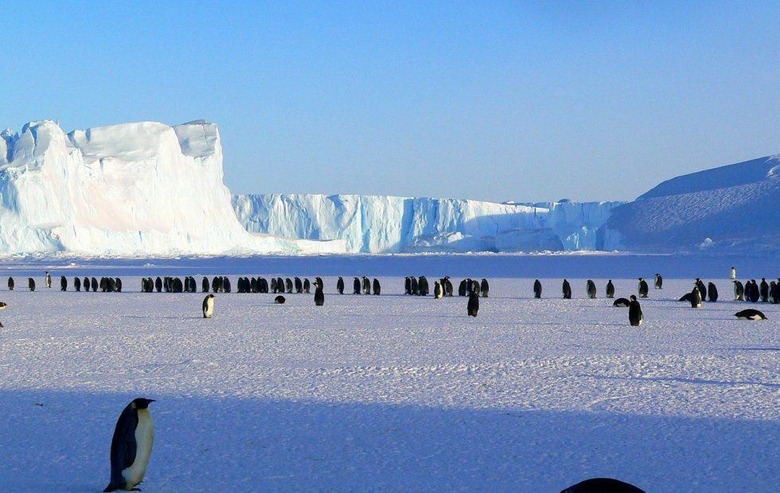

Penguin super colony found thriving on Danger Islands

A massive collective of penguins forming a super colony have been discovered in a part of Antarctica that hasn't been impacted by climate change. The colony features around 1.5 million penguins, according to a newly published study detailing the collective, and they're described as "thriving" in their remote, icy home.

The super colony is comprised of Adélie penguins, which were discovered by penguinologists from Oxford, Stony Brook, Northeastern, and Louisiana State Universities, as well as the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The researchers were working based on satellite imagery captured by NASA in 2014, that itself hinting at the existence of large penguin colonies on the Antarctic Danger Islands.

The team performed a census of penguins on the islands using multiple methods, ultimately finding 751,527 pairs; this is the largest population of its kind in the Antarctica Peninsula. Of particular interest is the fact that these penguins appear to be thriving, whereas penguin populations in many other places are declining.

Researchers aren't certain about why this penguin super colony has remained stable and strong for so long, but they have their suspicions. Declines in colonies in other parts of the Antarctic have been in regions associated with a relatively large human presence and negative impacts from climate change. The lack of humans and effects from climate change may contribute to the super colony's ability to thrive on the Danger Islands.

Talking about the findings is Oxford's Department of Zoology researcher Dr. Tom Hart, who said:

This was an incredible experience, finding and counting so many penguins. Scientifically, while this is a huge number of 'new' penguins, they are only new to science. Satellite imagery going back to 1959 shows they have been here all along. It puts the East Antarctic Peninsula in stark contrast to the Adélie and chinstrap penguin declines that we are seeing on the West Antarctic Peninsula. It's not clear what the driver of those declines is yet; the candidates are climate change, fishing and direct human disturbance, but it does show the size of the problem.

SOURCE: University of Oxford, Nature