MIT creates a hydrogel shell to keep bacterial sensors from escaping into the wild

Scientists have been developing strains of engineered bacteria that are intended to be used as sensors for detecting environmental contaminants. The bacteria can be used to detect contaminants like heavy metals. If deployed in the environment, the sensors can help the scientists track how pollutant levels change over time across a wide geographic area. The caveat is that there was some concern that the genetically modified bacteria might escape into the wild sharing their genes with other organisms.

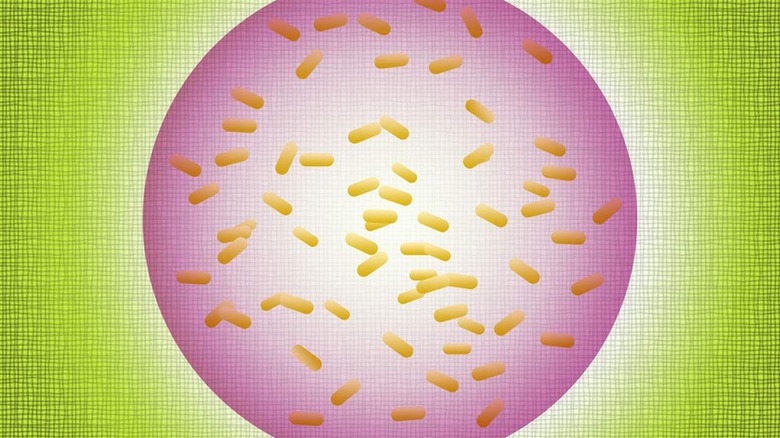

MIT engineers believe they have devised a way to make the deployment of bacterial sensors safer by encasing them in a tough hydrogel shell preventing them from escaping into the environment. Researchers on the projects found they could embed E. coli into hydrogel spheres allowing them to detect contaminants they're looking for but isolate them from other organisms.

The hydrogel spheres also protect the sensors from environmental damage. The bacteria in question were engineered to express genetic circuits they don't usually have, giving them the ability to detect various molecules. The circuits are designed so that the target's detection triggers the production of green fluorescent protein or bioluminescence. The bacteria also recorded memory of the event in the cell DNA.

Genetic circuits required to do this in the bacteria often include genes for antibiotic resistance. Researchers say that a particular gene allows them to ensure the genetic circuit is correctly inserted into the bacterial cells. It's easy to understand how genetically modified bacteria with a gene making them antibiotic-resistant could be harmful if released into the environment. Many bacteria can exchange genes between different species using a process called horizontal gene transfer.

To prevent that kind of gene exchange, the researchers in the past used a strategy known as "chemical containment" involving designing the bacterial sensors so they require an artificial molecule they can't get in the wild. Another challenge is that in a very large population of bacteria, there is a chance that a small number would acquire mutations allowing them to survive without the molecule.

In this study, the researchers leaned on physical containment by encapsulating bacteria within a device, preventing them from escaping. In the past, materials like plastic and glass were used but didn't work because they form diffusion barriers that prevent bacteria from interacting with the molecules they need to detect. By encapsulating the bacteria in hydrogels with pores large enough to allow molecules like sugar and heavy metals inside, the bacteria is protected and can still detect heavy metal molecules.