HERE's how you prove smart cities are the future

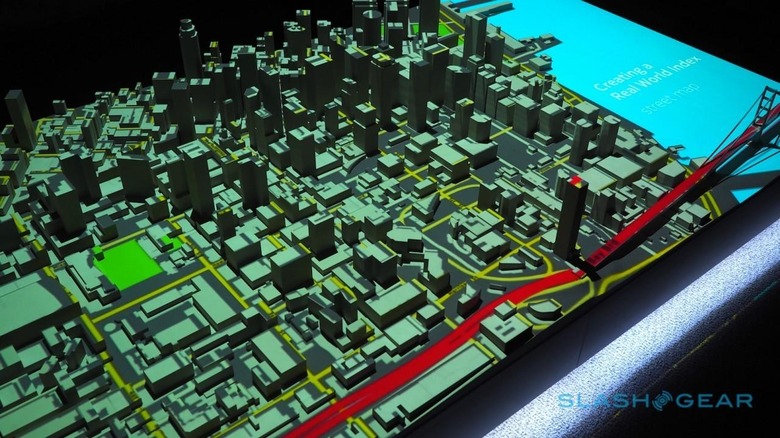

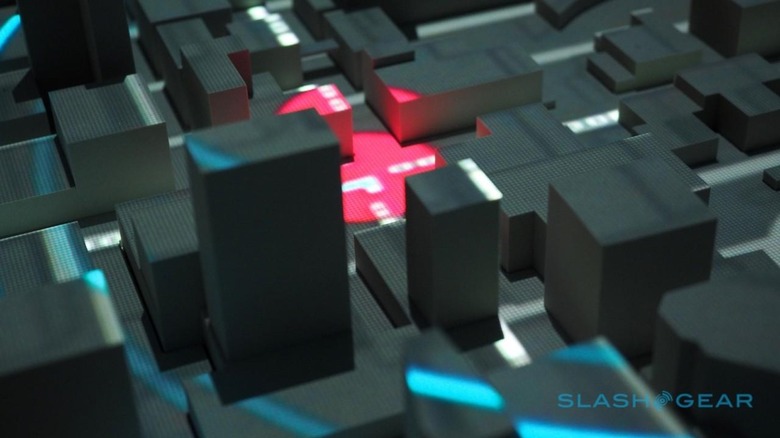

Turned off, HERE's 3D cityscape is the sleeping San Francisco that never really exists. The white, stylized version of the California tech hub – complete with a miniature chunk of the Bay Bridge – is tranquil in a way the real thing could never be. Turn on the projector overhead, though, and the city is flooded with data and light.

It's the demonstration HERE uses to woo potential customers to its cloud-centric location services, but for the first time they're showing it to press, too. Shipped over from Berlin, Germany, where HERE has its main offices, to the company's tech hub in Berkeley, California, right now the 3D projection system is not only unique but a victim of its own persuasiveness.

"Right now we only have one, but we're building a second," Pino Bonetti, HERE's social media manager, told me. "We have to ship it between Berlin and California, and it costs a lot to do that."

HERE is having to think a lot more about how it'll pitch its services to possible buyers these days. A Nokia company since 2008, it's close to semi-independence after a consortium made up of Mercedes-Benz, Audi, and BMW decided its high-resolution maps were worth too much for autonomous driving and other purposes for it to be absorbed by Google, Apple, or another tech industry heavyweight.

The deal still hasn't closed – for the moment HERE is still part of Nokia and so for legal reasons the mapping company can't start making plans with its new investors – but excitement levels among the staff is high. "It's the best thing that could've happened to us," more than one employee tells me during a day behind the scenes.

HERE is wary of it being called an "acquisition"; instead, Bonetti prefers, it's an collaborative investment with effective independence for the company as a result.

"The reason of the acquisition is to keep HERE open and independent," he told me. "Using the word acquisition is maybe setting a different expectation – it's about us being independent and these three companies putting in the money for that."

While the trio of automakers are already customers for HERE's mapping data – first developed during its time as NAVTEQ, a company dating back to 1986 – which powers a large proportion of standalone and manufacturer-fit car navigation systems, its technologies will still be up for sale to anybody with a vested interest in location-based services.

How do you convince people that such things are worth investing in? One way is to encapsulate how just a fraction of the data HERE collects and processes in the course of a day could be used to improve the flow in cities.

The first demo, dubbed Digital Transportation Infrastructure (DTI), follows a driver through HERE's pseudo-San Francisco traffic. When an accident takes place, not only does the car get re-routed around it – its connected navigation system getting a heads-up from other traffic closer to the scene – but HERE can use data from each of the driver "nodes" to feed information on things like which stoplights are green back to the city.

That could help route emergency services more effectively, but the real-time analysis of driver data has plenty of other applications. In a second demo, the "living city" unlocks everything from the cheapest place to park or find gas, through to the sort of live pattern data that self-driving cars will demand.

HERE hasn't been quiet in its argument that high-resolution – or "HD Maps" – are the key foundation to autonomous vehicles. All the same, the practicalities of collecting such mapping data mean while it can be the backbone to a system, it's not sufficient in its entirity.

The other half to the equation is the common sensor language, an open-source proposal for a standardized way for smart cars to communicate with a centralized cloud. Though sufficiently agnostic to be able to understand any automaker outlier insisting on using its own system, HERE's lure is the promise of much faster response times if cars themselves do the heavy lifting using things like GPU accelerated processing onboard, leaving the cloud to mash up the data and then distribute it back among nearby traffic.

It's early days for the system, though Bonetti tells me that two group meetings have already been held with a variety of car manufacturers and other potential participants, and a third on the calendar. It'll also take some advances in car connectivity; though a trial of the system is set to begin in Finland next year, using LTE networks, HERE expects 5G to be pretty much required for millisecond communication of accidents and other high-priority notifications.

For the moment, early iterations of the Digital Transportation Infrastructure system are already finding their way into production cars and US cities. Volvo's new XC90 uses it, with real-time traffic redirection, automatic road sign recognition, remote programming of the navigation system, and more, while states including Georgia, Alabama, and Missouri are all working with HERE on real-time data for select roadways.

In parallel, self-driving prototypes have been out on the road for some time already, in many cases using HERE's mapping technology.

"On the one hand the requirements from our customers out of what they want from a map is going way up, the accuracy and the features," Mark Tabb, the director of engineering at HERE who leads map automation and sensor processing, says, "and on the other hand the freshness. And autonomous cars are really driving it."