Harvard says stem cell genes can be edited in living systems

Researchers at Harvard University have shown that gene-editing systems can be delivered directly to where the cells live rather than being used in a petri dish. The researchers believe the findings have significant implications for biotech research and the development of treatments for genetic diseases. Researcher Amy Wagers says that to correct disease-causing gene mutations, the relevant stems cells must be changed.

If those cells aren't changed, whatever fixes are made in other cells are eventually replaced with diseased cells. Fixing the stem cells causes the replication of healthy cells that will eventually replace the diseased cells. Right now, stem cells have to be extracted, kept alive, genetically altered, and then put back into the person's body.

That process is disruptive to the cells, and they may be rejected or fail to engraft back into the person. She says that making changes without having to remove the cells would preserve the regulatory interactions of the cells. Wagers team used an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that infects human and mouse cells, but doesn't cause disease, as a transport vehicle.

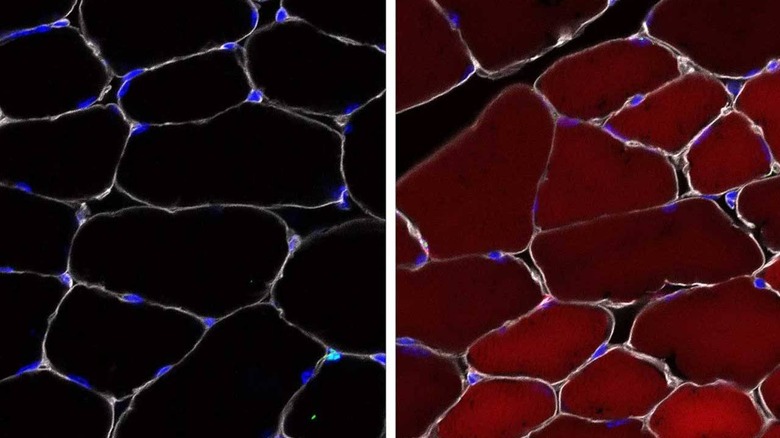

The team designed gene editing cargo packed into the AAV that would be delivered into several different types of skin, blood, and muscle stem cells as well as progenitor cells. To verify the function of their cells, the team used mice and activated a "reporter" gene using their method that makes the cells bright, fluorescent red when the reporter gene is activated.

The team found that the new method is up to 60% effective with up to 60% of the stem cells turned red in skeletal muscle. Up to 27% of the cells that make different types of skin turned red and up to 38% of stem cells in bone marrow turned red. The team notes that even a single healthy stem cell could be enough to stop a defect.