COVID-19 vaccine rules see FDA try to win over anti-vaxxers

Fearing skepticism or even outright refusal among some Americans to consider a COVID-19 vaccination, the US Food and Drug Administration has preemptively published its guidelines for the development of a lasting coronavirus treatment. The recommendations, released today, cover the process by which the FDA will eventually approve potential COVID-19 vaccines, at least in part to try to bring "anti-vaxx" advocates onboard.

Several potential vaccines are currently undergoing development or clinical trials, as pharmaceutical companies attempt to figure out how the ongoing spread of the coronavirus pandemic could be curtailed. Timelines for exactly how long they'll come to fruition, however, vary widely depending on who you ask.

The reality is, though, that the success of a vaccine isn't only based on its clinical efficacy, but by the number of people to whom it's actually administered. That's something which can't be taken for granted, particularly in America where, over recent years, skepticism and outright mistrust of vaccinations has flourished. Although broadly considered by the scientific and medical communities to be safe, vaccines to prevent conditions like polio and measles have become contentious and politically charged.

It's a reality that the FDA clearly acknowledges. "We recognize the urgent need to develop a safe and effective vaccine to prevent COVID-19 and continue to work collaboratively with industry, researchers, as well as federal, domestic, and international partners to accelerate these efforts," Stephen M. Hahn, M.D., commissioner at the agency, said today in a statement. "While the FDA is committed to expediting this work, we will not cut corners in our decisions and are making clear through this guidance what data should be submitted to meet our regulatory standards. This is particularly important, as we know that some people are skeptical of vaccine development efforts."

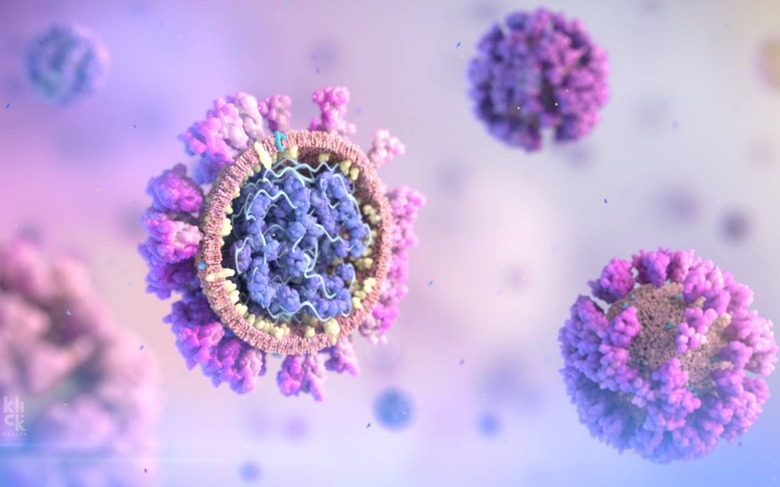

Multiple different approaches have been undertaken to attempt to stymie the spread of COVID-19. Live-attenuated vaccines, for example, use a weakened or modified version of the virus itself, and are based on the assumption that, after exposure, the body can develop its own immune response should it later encounter coronavirus in the wild. Inactivated vaccines, meanwhile, use a neutralized version of the virus.

Other approaches take some of the specific elements of the virus – such as its casing, or capsid – and work by training the body on how to overcome them. That's the approach used by the whooping cough vaccine, for example, and the vaccine for Hepatitis B. Finally, there are toxoid vaccines, which rely on the body developing immunity to the toxins produces by a virus, rather than the virus itself.

"Vaccines have been highly effective in preventing a range of serious infectious diseases," the FDA pointed out today. "The FDA has the scientific expertise to evaluate any potential COVID-19 vaccine candidate regardless of the technology used to produce or to administer the vaccine. This includes the different technologies such as DNA, RNA, protein and viral vectored vaccines being developed by commercial vaccine manufacturers and other entities."

The goal with the new "Development and Licensure of Vaccines to Prevent COVID-19: Guidance for Industry" document is to outline just what is expected from potential vaccination manufacturers if they want to eventually get FDA approval. It covers factors like the sort of clinical testing that will be expected to have been undertaken, including ensuring that sufficient diversity has been accounted for. Plans for vaccinating pregnant people are also encouraged.

There's also an expectation around efficacy. The FDA "would expect that a COVID-19 vaccine would prevent disease or decrease its severity in at least 50% of people who are vaccinated," it explains.

Whether any of this will be sufficient to convince vaccine skeptics to consider taking a future treatment once approval is granted, however, remains to be seen. During the 2018-19 flu season, for example, vaccination coverage among adults was just over 45-percent. Research by The Conversation in early May 2020 found almost a quarter of those surveyed (23-percent of 493 participants) said they would not get a COVID-19 vaccination when such a drug becomes available.