Don't be blind on wearable cameras insists AR genius

The augmented reality researcher at the center of allegations of assault over sporting a wearable computer in public has warned that ubiquitous cameras – and the potential for privacy incidents – are only going to increase. Professor Steve Mann, the father of wearables who claimed McDonald's staff in Paris assaulted him and damaged his advanced EyeTap headset earlier this month, fired back at criticisms that his constantly-running camera was a provocation to the privacy-minded. "Ironically the people most frightened of cameras seem to be the ones who are pointing cameras at us (e.g. big multinational organizations)" Mann argues.

Mann makes only a side reference to the McDonald's incident, pointing out that the restaurant has "denied assault or destruction of my property, despite solid evidence that I have provided to the contrary." Instead, he lists the ways cameras and being observed have worked their way into our daily lives, and sets out an argument for why a balance of surveillance and sousveillance (literally "watching from below"; in effect the observation of a situation from an individual within that situation) is an inevitability.

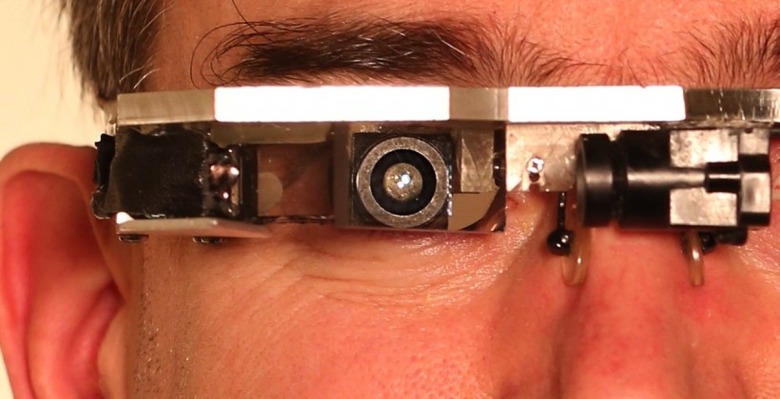

Mann's EyeTap actually captures at a rate of 120fps and in groups of three; a little known fact is that the researcher actually patented HDR (High Dynamic Range) photography two decades ago, and the trio of differently exposed images are combined for a single view that combines more detail than would be possible with a regular camera or the human eye unaided. "If I see and remember something (whether a temporary short-term image cache, or permanently), and use it for my own use, I have not violated anyone's privacy" Mann suggests.

"Some of us have experienced resistance to this [DEG (Digital Eye Glass)] technology, as some people are frightened of cameras. Ironically the people most frightened of cameras seem to be the ones who are pointing cameras at us (e.g. big multinational organizations that use lots of surveillance cameras in their own establishments). My own experience with EyeTap DEG is that objections raised by individuals are usually appeased by a simple explanation of what the eyeglasses do, and how they help me. Basically individuals can work things through. But when a large organization has a policy against cameras, we have a fundamental problem that, on the surface, would seem to have a chilling effect on mass acceptance of DEG" Professor Steve Mann

The ex-MIT professor contrasts his own wearable camera – which, in normal use, does not retain images, but only saved the shots of the McDonald's workers challenging Mann because a damage-related security system was triggered – with the cameras installed into modern street lighting which adjusts brightness depending on whether the road is in use (but which may also end up tracking peak utilization or even watching for crimes). Part of his argument is around personal use and transience of storage; a camera versus a "seeing aid".

"In a world where people interact face-to-face, in often crowded spaces, a wearable camera is in itself not necessarily a violation of privacy when the images are used only for personal use. In fact surveillance is a greater privacy violation than sousveillance because, for example, when you're alone, you might still be on camera" Professor Steve Mann

Overall, though, Mann points out that cameras aren't going anywhere, and that a head-in-the-sand approach to wearables – suggesting, say, that the world simply isn't ready for sousveillance technology – is pointless. "To try and stop picture-taking in 2012 is almost impossible."

"When we're surrounded by "smart lights", "smart toilets", "smart refrigerators", and the like, what's wrong with having "smart people"? That is, what is wrong with putting intelligence on people?" Professor Steve Mann