Bleached coral seems to be fixing itself with neon pigment shields

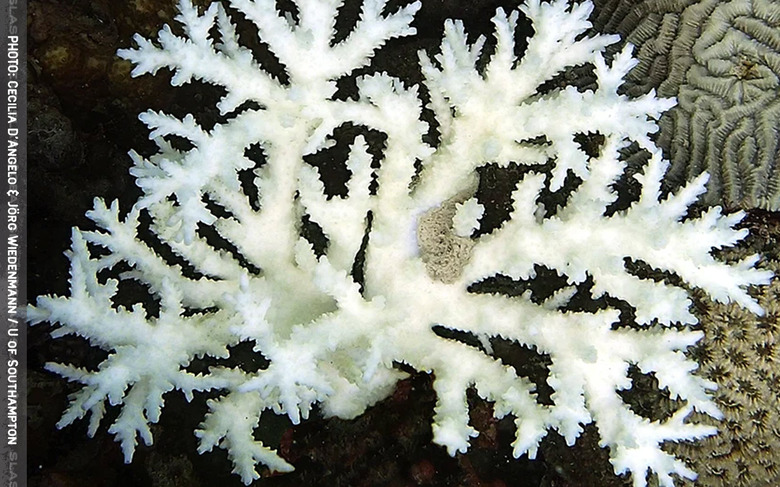

In its healthy state, coral is yellow-brown, green, red, and generally a variety of tones that feel "natural" to our human eyes. In its healthy state, coral's yellow-brown symbiotic pigments allow the absorption of blue light. Bleached coral is caused by temperature, light, pollution (like carbon), and other disruptions. Recent investigations into bleached coral's revealed some odd changes in the reef – bright, almost unnatural colors exhibited by coral that'd previously been bleached to the color of bone.

Coral starts with and thrives on marine algae called zooxanthellae. This algae works with photosynthesis to live, providing coral the energy to thrive and reproduce. When coral is stressed, algae is expelled, and we see a "bleached" result. This is the color of the internal structure of the coral.

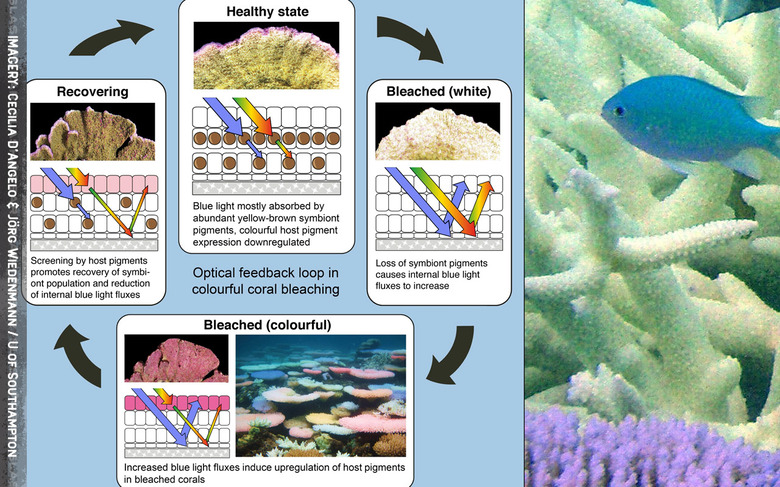

Once coral is "bleached", internal blue fluxes increase. For some coral, the next step is increased blue light fluxes inducing upregulation of host pigments. It's almost as if these neon tones are the "true" color of the coral – and it would APPEAR to be a good sign!

Colorful bleached coral is shown to create its own "screen" for light, allowing the regulation of internal blue light (reducing internal blue light fluxes). This new protection provided by the wild, bright, "natural" color tones promote recovery of symbiotic algae.

In the latest research on this subject, researchers found that more shallow coral produced more intensely bright and colorful protective pigment. The deeper the coral, the less pigment was produced. Different types of coral produced different tones, sometimes wildly different in very close proximity.

"Reports suggest that colourful bleaching occurred on some parts of the Great Barrier Reef in March and April 2020, so some patches of the world's largest reef system may have better prospects for recovery after the recent bleaching," said a report in Science Alert written by two researchers that participated in this latest coral project. That was Jörg Wiedenmann, Head of the Coral Reef Laboratory, University of Southampton and Cecilia D'Angelo, Senior Research Fellow, Coral Reef Laboratory, University of Southampton.

You can learn more about this loop of nature by reading the report in Current Biology. The research paper goes by the name "Optical Feedback Loop Involving Dinoflagellate Symbiont and Scleractinian Host Drives Colorful Coral Bleaching" and can be found with DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2020.04.055 as of May 21, 2020. This research was authored by Elena Bollati, Cecilia D'Angelo, Rachel Alderdice, Morgan Pratchett, Maren Ziegler, and Jörg Wiedenmann.