Apple made some huge M1 Silicon claims today

There's no reality distortion field quite like Apple's, or so the thinking goes, and that's even more the case when it comes to a huge architectural shift like the launch of the M1, its debut homegrown chipset for Mac. First of the Apple Silicon line-up to be announced since the company confirmed it would be phasing out Intel and moving to its own SoC design back at WWDC 2020 a few months ago, the M1 will initially be at the heart of a new MacBook Air, MacBook Pro 13, and Mac mini.

That's just the start, of course. Over the next couple of years, Apple expects a clean-sweep for its chipsets through the whole of the Mac range. While currently the M1-powered machines will coexist with their Intel-based brethren, that balance will continue to tip in Apple Silicon's favor.

It'll be a family of chipsets, not a single model, and it's fair to say the M1 likely leans hard on what we've seen Apple already deliver with its iPad Pro hardware. The priorities may be slightly different – bigger batteries mean Apple can afford to push the eight CPU cores harder, for example – but as Apple SoCs go this is evolutionary, even if for Mac it's the start of a revolution.

With the big ambition comes big promises, and Apple's "One More Thing" presentation today wasn't short of them. In the fanless MacBook Air with M1, for example, the new chipset's CPU is up to 3.5x faster than the old Air with Intel's dual-core processor. The GPU is up to 5x faster, helping export iMovie projects up to 3x faster, support multiple streams of 4K ProRes video in Final Cut Pro for the first time on an Air, and export Lightroom photos in as little as half the time.

The claims get even more impressive on the MacBook Pro 13 with M1. That, Apple says, can render 3D titles in Final Cut Pro up to 5.9x faster, while the laptop is up to 3x faster than a similarly-priced Windows 10 notebook running an Intel Core i7 processor and Intel Iris Plus graphics.

Without the constraints of potentially running on a battery, the new Mac mini can squeeze the most out of the M1 chipset. That means up to a 6x increase in graphics performance versus the old model, Apple says, or 5x the performance of the best-selling Windows 10 desktop (using a Core i5 processor and Intel UHD Graphics 630).

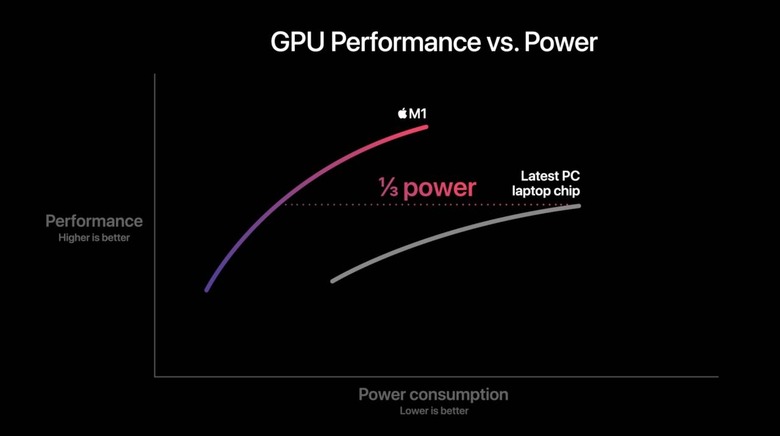

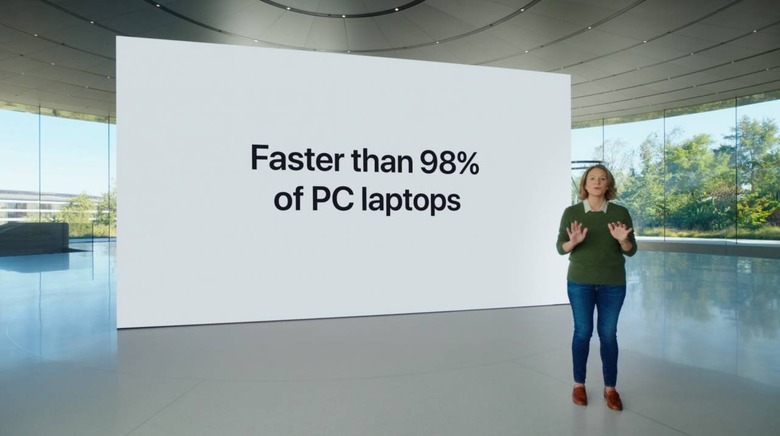

As you'd expect, though, there's no shortage of small print to deal with. The M1-based MacBook Pro, for instance, can support peak performance for longer, Apple says, courtesy of its active cooling; the implication is that the new MacBook Air may be able to hit those highs, but it won't be able to maintain them for as long. Benchmarking, too, is a mysterious art, and while Apple had plenty of graphs showing how much more potent its SoC is than the Intel competition, they tended to be light on actual figures.

There's good reason for that sort of hedging, of course, beyond just wanting to make for a clean and peppy presentation. Apple still uses plenty of Intel chips in its Mac line-up, and while some of them – like the MacBook Pro 13 – now offer the choice between Apple Silicon and Intel x86 processors, most don't. Pulling out the rug from underneath the majority of your computer range would be a questionable strategy.

The other big factor is that benchmarking itself is pretty troublesome, particularly as you get into areas like machine learning. Just as we've seen for smartphone chips, the reality is that like-for-like comparisons are not only pretty much impossible, they also require underlying assumptions about the sort of tests that are appropriate and applicable to day-to-day use. Though the industry – and those who observe it and comment on it – loves to pit one platform against another, the complexities of accurate and useful benchmarking illustrate well the old adage that the map is not the territory.

As always, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating. We won't have long to wait there, either: these first three M1-based Macs will ship from next week, and Apple's timeline for revamping all of its models with an ARM chipset inside is aggressive. Soon, individual users will be able to see for themselves which of their daily workflows are faster, and which are slower, and what impacts those experiences. Apple can control the overall ecosystem better when it's making both the hardware and the software, we've seen that with iPhone and iPad, but it can't make a single device that's everything to everyone.

What's abundantly clear, though, is that Apple isn't playing it safe. The MacBook Air, MacBook Pro 13, and Mac mini are three of its most popular products, and while the stars may have aligned for making them the launch candidates for the M1 chipset, it's also a big risk moving those users over to a new architecture. The number boasts may have been big today, but the bigger message is that Apple Silicon is shaping up to be even more of an upending than the Mac switch from PowerPC to Intel was 15 years ago.