Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier just lost a 100 square mile chunk of ice

Remember the Larsen C ice shelf that finished breaking earlier this year? Researchers are saying that Antarctic just lost yet another giant chunk of ice, this one measuring 103 square miles in size. To put that in perspective, the now-floating ice is more than four times the size of Manhattan, though it is much smaller than the calving that happened a few months back.

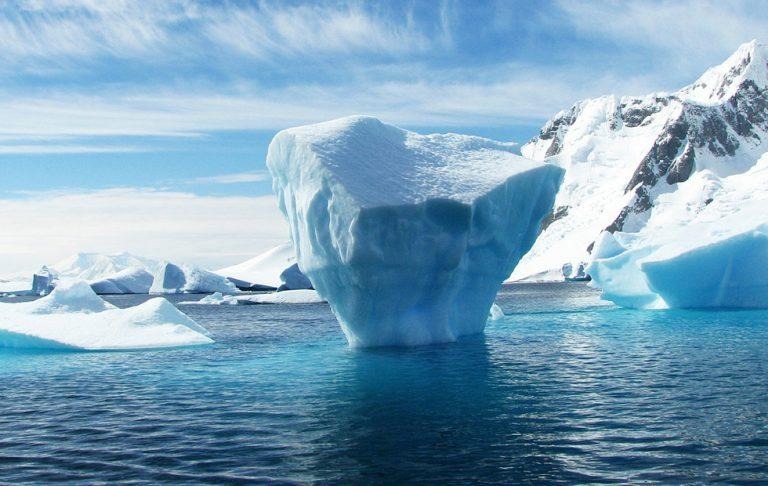

The calving event took place on Pine Island Glacier, which lost a piece of ice said to comprise 103 square miles. That size makes this the 5th largest calving event to happen in the last 17 or so years, and is the second to happen this year alone. The calving was spotted by the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, according to The Washington Post, which shared a satellite image (below) of the newly formed ice berg.

Breaking news from Pine Island Glacier, which lost 267km2 of icebergs today, after the internal crack resulted in a large calving event 1/n pic.twitter.com/sLwGTyNTfC

— Stef Lhermitte (@StefLhermitte) September 23, 2017

The Pine Island Glacier is no stranger to such calving events, and in fact has been carefully monitored by researchers around the world who worry these rifts are highlighting a trend. Speaking to WaPo, researchers said that while rifts typically form along a glacier's sides, Pine Island is experiencing them from the bottom and in the middle, something possibly caused by warmer waters that are weakening the glacier's base.

Researchers went on to explain that smaller, thinner cracks have been spotted on the glacier, and that these may indicate that small pieces of ice could break off in the near future. Increased retreat on the glacier may speed up its rate of ice loss, a problematic scenario that will have a notable effect on sea levels. This glacier experienced a 225 square mile calving in 2015 and a 252 square mile calving in 2013.

Changes in the calving behavior over recent years have caught researchers' attention, though they're not ready to state what the total effects of this will be. Continued research into the matter will no doubt produce more details in the future, but in the meantime it serves as another example of the issues that warming oceans present.

SOURCE: The Washington Post