Transparent solar panels could revolutionize cities & tablets

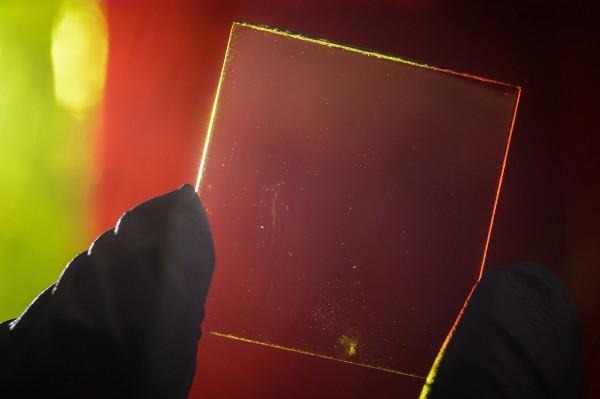

Transparent solar cells that could one day mean your home, office, or even car windows are generating electricity have been developed, as well as opening the door to phones and tablets that create their own power. The research, led by a team at Michigan State University, has come up with a transparent luminescent solar concentrator which looks clear to the eye but can still harvest energy from wavelengths of light invisible to humans.

While the team, led by Richard Lunt, concedes that theirs isn't the first such attempt to make transparent panels, it's so far the only one to do so without resulting in a tinted sheet.

The clever part is how organic molecules in the pane can absorb very specific, non-visible wavelengths of sunlight in the ultraviolet and near-infrared ranges. They then glow with a different infrared wavelength.

That glowing light is diverted to the edges of the sheet, where photovoltaic solar cells have been placed.

"Because the materials do not absorb or emit light in the visible spectrum," Lunt pointed out, "they look exceptionally transparent to the human eye."

The downside, at this stage at least, is how efficient the panels are. Currently, the cells are converting at a rate of "close to 1-percent"; Lunt's team expect to be able to stretch that to beyond 5-percent by the time the system is refined.

Still, even though it may not be the most powerful method of collecting power, it could become more ubiquitous than existing solar cells.

Lunt envisages buildings with plentiful glass as being ideal for the technology, since the windows themselves could double as power generators. Similarly, the cover glass on ereaders, tablets, smartphones, and other devices could be given a secondary purpose as solar cells, helping offset the extra electricity required for increasing backlighting for outdoor use by virtue of the sun itself.

It's not clear when the transparent solar tech might be commercialized at this stage, nor how it compares in price to existing panels.

VIA Gizmodo

SOURCE Michigan State University