This futuristic exoskeleton convinced me to take aging seriously

One day you will die, but, before then – and assuming all goes to plan – you'll be trapped in an old body. Failing eyesight, hearing plagued with tinnitus, and limbs progressively seizing until just getting up from your chair is a challenge too great: death may be considered the biggest taboo, but aging is arguably a more uncomfortable one. With all that to look forward to, it's no surprise that nobody wants to talk about getting old. Could a futuristic exoskeleton kick-start that conversation?

That's what insurance company Genworth is hoping, and it brought the fruits of that ambition, the R70i suit, along to the Aspen Ideas Festival 2015 to test the theory.

"Our mission is to prepare families for their futures," Janice Luvera, global brand leader at Genworth, points out. "The good news is that we're living longer. The bad news is that they're not really prepared for it."

Genworth's answer is a combination of outspoken celebrities – like Angela Bassett, known for her roles in American Horror Story and What's Love Got to Do with It – discussing the personal impact of family members aging, and a technological shorthand to put those currently feeling spritely into the body past its physical prime.

"It's not just an issue for older people any more, it's an issue for society," Luvera concludes. "How are we going to take care of this aging demographic when they're not prepared for it?"

Figuring out a way of initiating and framing that conversation was the challenge Genworth took to Bran Ferren, co-founder and chief creative officer of Applied Minds. You may not have heard of him, but there's a good chance you've experienced something he's worked on over his unusual career.

An MIT dropout, Ferren threw himself into pyrotechnics and AV effects design. When he was 25 he started Associates & Ferren and worked on movies like Star Trek V: The Final Frontier and Little Shop of Horrors, along with Pink Floyd, Depeche Mode, and David Bowie on concert effects.

After the company was acquired by Disney in 1993, Ferren worked on technology projects for Disney Theme Parks among other things, including the Tower of Terror ride. It was from the Disney Fellows Program that Ferren created in 1996 that he began working with Danny Hillis, and the two founded Applied Minds in 2000.

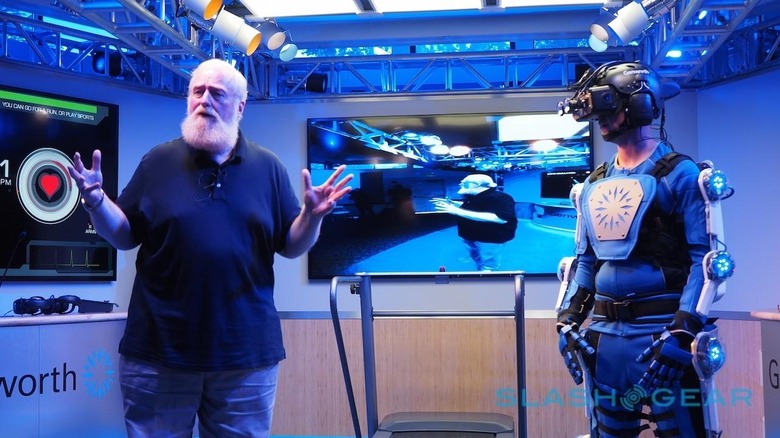

Since then, Ferren and Hillis have turned their talents to cooking up new and interesting gadgets and technologies, the Genworth R70i suit being a good example. Handiwork of around 35 people over the past couple of years, it's the physical embodiment of the big problem around aging: nobody wants to talk about it.

"What kind of thing can we build that will make it easier to have these conversations?" Ferren questioned. "How do you start a conversation about something that people have an aversion about?"

I'll confess, I'm not always the most patient person. I walk fast in airports and along the sidewalk; I get frustrated when the people around me are slow, or in my way. I'm British, so I don't say anything at the time, but I roll my eyes.

Basically, I'm the ideal uppity stooge to get taken down a peg or two by Genworth's suit.

Donning the R70i isn't done casually. First, you have to strip down and squeeze into a neoprene onesie – the technicians ominously warned me that it was going to get hot and sweaty – and then stand patiently while they construct the rest around you.

It's a little bit like being Tony Stark, only rather than getting Iron Man's suit you're being aged a handful of decades in one fell swoop.

The R70i itself is both complex and straightforward. All of the processing for the head-mounted display, the audio system, and the limb joints is done by a computer in the backpack, power packs slotting into place underneath.

Each of the joints at hips, elbows, and knees has a simple ball and socket assembly inside. When activated – the LEDs gleaming through the plastic cover go from happy blue to ominous red – a servo tightens up a screw against the ball, restricting its movement.

Genworth suits you up in front of a mirror, and as I watched the futuristic exoskeleton get strapped, Velcro'd, and clamped into place, I initially had the opposite reaction I was perhaps meant to.

"This isn't so bad," I remember thinking, "I look like a Power Ranger."

What I hadn't realized was that the exoskeleton was dangling from a support frame, something which became suddenly and abundantly clear when the engineers released if from its hook and my body was forced to take the whole weight of it. Then how convincingly I could cosplay was the least of my considerations.

Clomping out into Genworth's demo area, the framework forcing deliberate and jerky motions, you quickly end up walking like a less-intimidating Robocop. What you see is pixelated and fuzzy, the resolution limits of the Oculus Rift headset and the stereo camera array downgrading the world around you with blurred edges. Sounds, relayed through microphones and into the earpieces, have a tinny resonance.

Each of those three areas – physical movement, vision, and hearing – get a focus in the aging demonstration. It's not meant to be an exact, scientific representation of what being old is like, Ferren argues: instead, the idea is to give people an understanding of what danger signs to look out for, particularly if someone else, like an elderly relative, mentions them.

That doesn't mean it's not effective. We started out with my eyesight, and to be honest, I'd not expected to be affected by the vision part. I've worn glasses since I was twelve, and so I'm used to regular eye-tests and hearing from opticians about what I should be cautious about.

Turns out, there's a pretty big different between hearing about it and seeing it for yourself. Genworth can simulate the onset of tunnel vision – your eyesight narrowing – and the growth of cataracts, as well as floaters drifting down, with Ferren twiddling knobs on a control board to adjust and mix the impact of each.

I've worn tunnel vision goggles before, their lenses mostly blacked out apart from a tiny patch of light in the center. What they don't convey is how insidious losing your vision is: not an all-or-nothing process, like donning a set of special glasses, but the gradual erosion of one of the sights I'm so reliant upon. Dangerously, many people don't notice it – or mention it – until it's all too late, and the changes are irreversible.

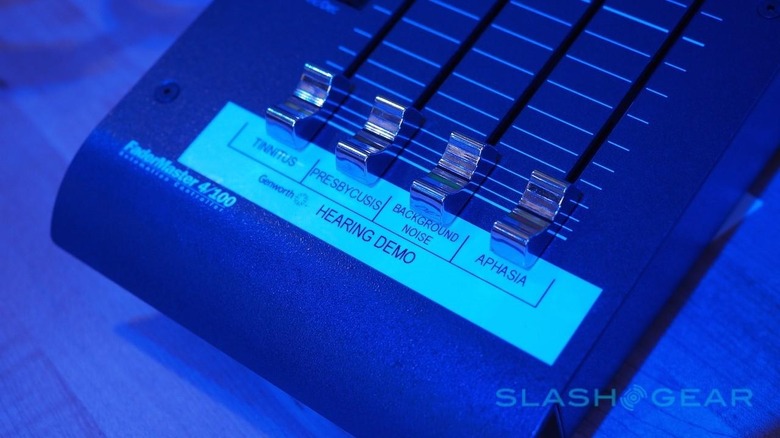

As for the audio demonstrations, Ferren first cranked up the artificial tinnitus before introducing background noise. Suddenly I found myself leaning in to him, instinctively trying to lip-read to augment my failing hearing.

Scariest of the audio demonstrations is the faux-aphasia, though. While officially a blanket term covering a wide variety of language disorders caused by damage to the brain, the R70i models it by playing back your voice through the headphones, only with a slight delay. The result is a sudden inability to process audio in the usual way, with your words jumbling as you try to speak them.

That's the theory, anyway. Having watched an earlier demonstration where the Genworth staffer in the suit was rendered almost incoherent, I was quietly proud of myself when I managed to recite "Mary had a little lamb" despite the echoes of my own diction ringing a split-second after.

Any gloating was short-lived, however, when Ferren tweaked the delay and suddenly I found myself tongue-tied, second-guessing every attempt to form a sentence until I gave up my gibbering. Rendered mute, the tinnitus and clinking glasses and hubbub of a cocktail party thrumming in my ears, I suddenly understood why so many older people might opt to sit back and tune out of social situations rather than face something so stressful.

Even the suit's not-inconsiderable heft adds to the reality of the experience. "The weight was specially picked and distributed," Ferren points out, "as you get older, you get fat." Meanwhile, your muscles get weaker and your joints start failing, meaning you end up noticing that extra weight all the more.

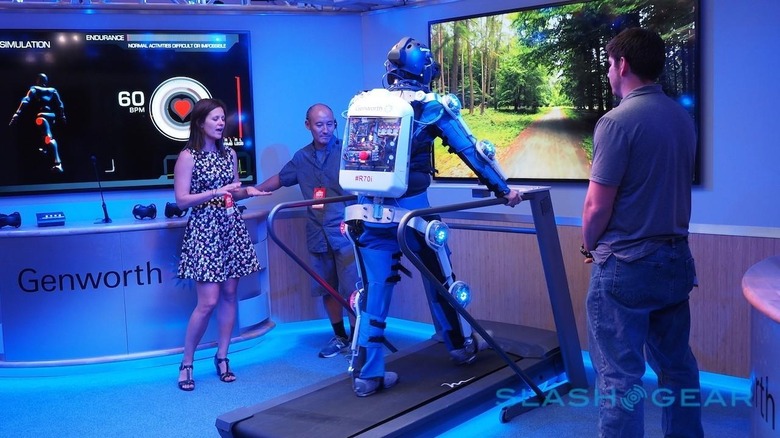

Not, perhaps, the ideal time to step onto a treadmill and go for a brisk walk, but that's where the last phase of the R70i experience took me. One moment you're stomp-stomp-stomping along like a relentless Terminator; the next, your leg joints suddenly start to seize up until it's taking everything in you just to stagger forward at something near your previous pace.

The sense of relief when the servos ease off is palpable, but short-lived. At least when the R70i locks up both legs you have some sort of balance; it's when Genworth targets just one leg, particularly when it's on your dominant side, that you really notice it.

Half-dragging my right leg behind me like a wounded animal, sweating inside the clinging bodysuit and resorting to pulling myself along on the handlebars of the treadmill – which suddenly felt more like a walking-frame – I realized I wasn't just an old person, I was decrepit.

Happily, Ferren isn't only looking to the R70i as a way to bring youngsters down a peg or three. Instead, it's also being used as a test platform for technologies that might one day prove assistive, up to and including strapping on a suit that could shave decades off your mobility.

"The exoskeletons, rather than being used to slow you down, will be the same things that replace muscle strength that is gone," Ferren explained. Right now, that's not something the current exoskeleton could do – the joints are only designed to get stiffer, not augment your abilities – but the real-time processing has more obvious corrective applications.

The same image and acoustic crunching done by the onboard computer could be used to help correct for aphasia and disrupted vision, Ferren points out. Cochlear implants are increasingly commonplace, and the technologist believes that optical implants are close at hand.

That's the technical side, at least. As for the rest, it's really up to us.

I took away more than just an existential feeling of dread about aging from my time in the R70i suit. I'm going to make more of an effort to wear sunglasses when I'm outside, because that can delay the onset of things like cataracts, and I'm going to stop assuming that migraines are part and parcel of a life spent in front of a computer screen, and instead could be a symptom of something that needs to be taken more seriously.

Most important, though, I'm going to try to talk about getting old, even if it's uncomfortable to do so.

Next up for the Genworth R70i is a roadshow around the US, while Applied Minds is working on next-gen suits that will be easier to make and less expensive, so that more can be built and more people can try them.

"The responsibility is really going to fall on younger people today, the millennials," Ferren concludes. "So it's important to educate younger folks, to get them educated, because that's where the burden is going to fall."