Robot Love: Inside Dean Kamen's FIRST Championship 2014

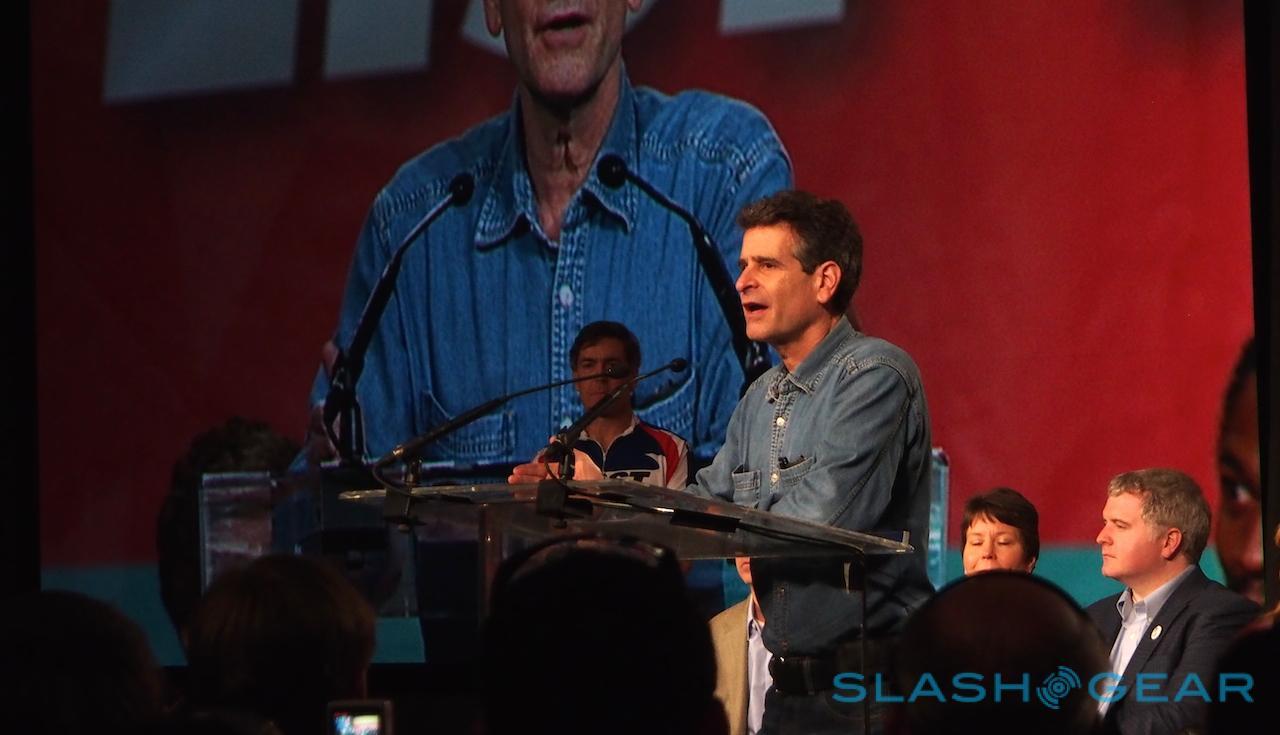

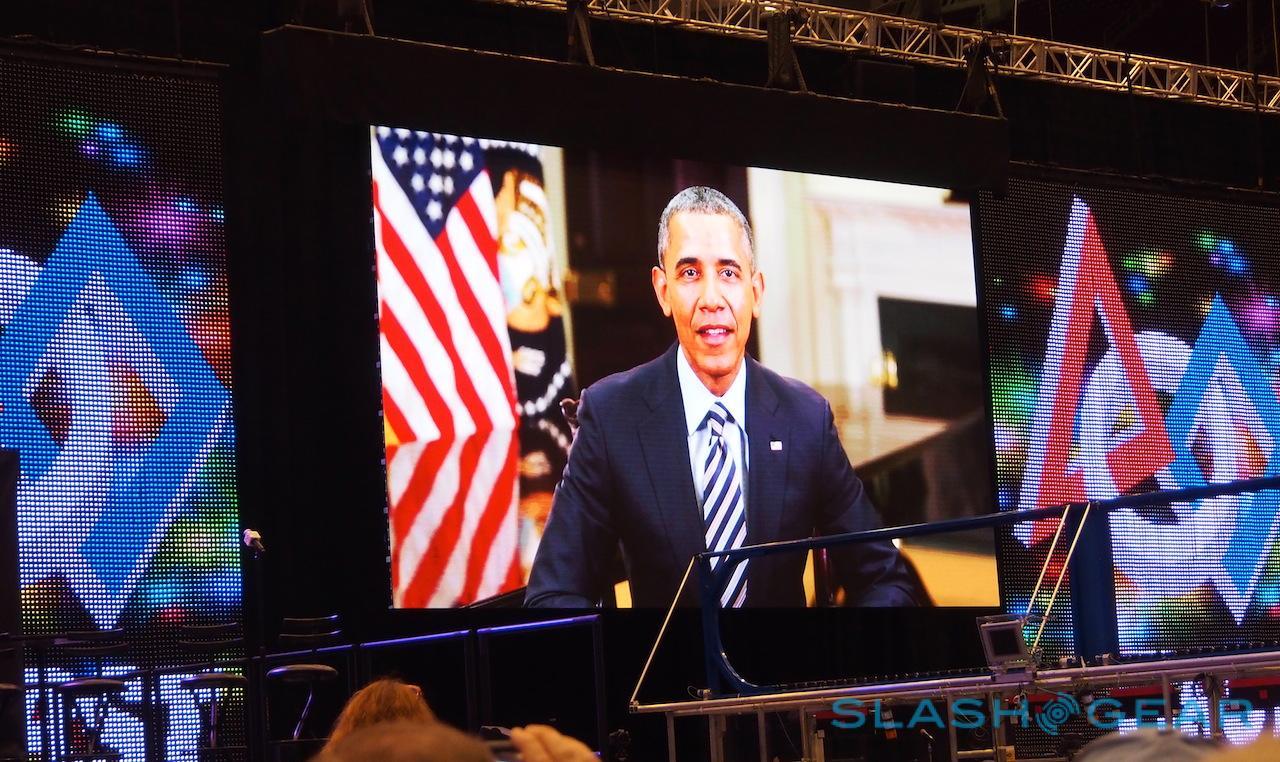

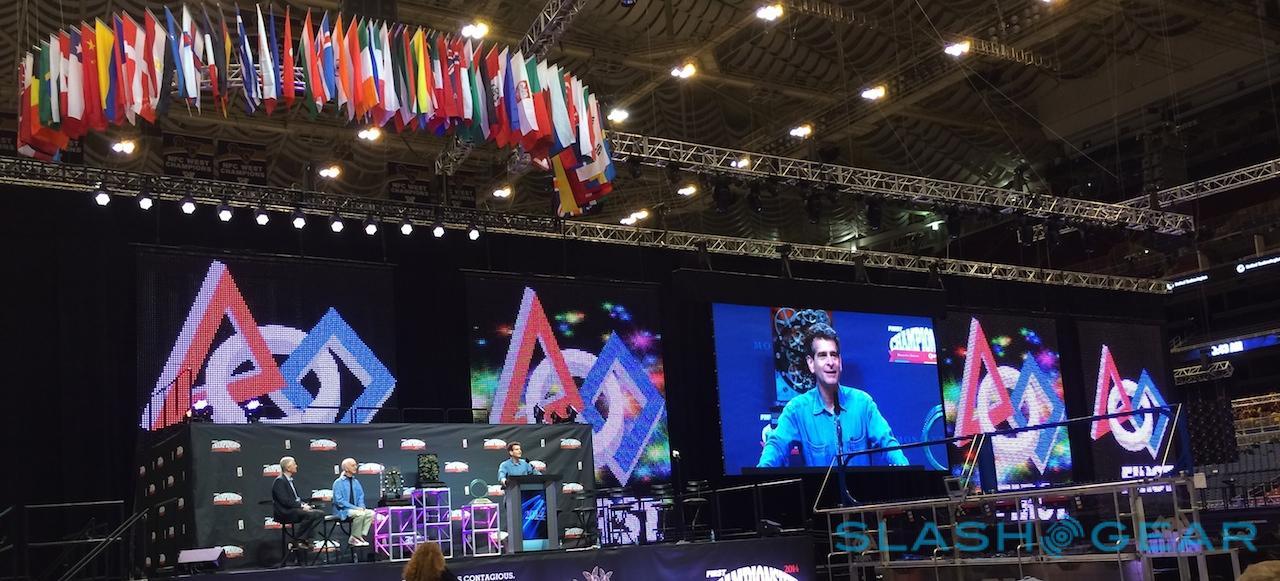

The screaming in the stadium is so loud, I can hardly hear the announcer. Enthusiasm spills from the stands in waves; only gets louder when President Obama appears on the big screen for an unexpected address. The Edward Jones Dome in St. Louis isn't playing host to the Rams as usual, however; instead, the seats are filled with row after row of students from K-3 up to high school age, all here for the FIRST Championship 2014. Brainchild of Dean Kamen – better known perhaps for being the father of the Segway – this is no ordinary robotics competition.

For years, there's been the assumption that the only type of contest between robots that audiences want to see is destructive. Robot Wars-style tournaments with crushing and dismantling at their heart; a Hunger Games for radio-controlled battlebots wielding drills, circular saws, and flamethrowers.

At the same time, rampant robots have become a mainstay of movies, but while we may like to watch them, there was increasing concern that too few young people were actually learning the skills to build the real-world equivalent of the CGI creations.

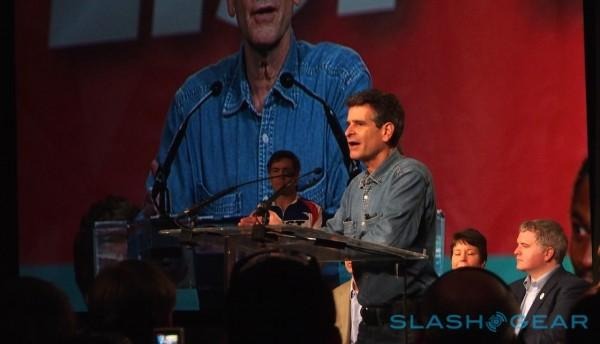

Dean Kamen decided to do something about it, founding FIRST in 1989. The "For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology" program aimed to promote the importance of science, technology, engineering, and math – or STEM, as the shorthand has it – using DIY robotics as its lure.

"When I saw how few kids in this country – particularly women and minorities – were even thinking of going into science and technology twenty-something years ago, I couldn't understand it," Kamen told me when I sat down with him during the games. "Because it was so clear to me technology is moving faster than ever, it's more exciting than ever, you can do cooler stuff than ever. Why aren't more kids doing this? Maybe our schools weren't great but they weren't better the year before; you can always use "oh, it's an education crisis," but I'm thinking none of those other things have changed, what's changed? What's changed is that we had a culture that had created superstars."

"The Super Bowl isn't a sport any more, it brings the country to its knees. Baseball isn't a national pastime, it's an obsession. And when you see how media is so powerful and effective at creating superstars from the world of entertainment and sports, something had to give. And what gave was kids' sense that science and technology and engineering was cool.

Adults, parents, grandparents... everybody around them was in this chain of little league, on up to junior varsity, to high school, to college. The infrastructure of America was built to turn everybody's attention to these pastimes. And I said, okay, what does a good inventor do? You take what's out there and you apply it in a useful way. I didn't have to invent a concept that would be engaging to kids, that would hook them, that would get them passionate" Dean Kamen, FIRST

Distilling what sports had done right into a recipe for engaging young people, Kamen says, turned out to be relatively straightforward. "It's after school, not in school. It's aspirational, not required," he explained to me.

"You don't get quizzes and tests, you go into competitions and get trophies and letters. You don't have teachers, you have coaches. You nurture, you don't judge. You create teamwork between all the participants. We justify sports for teamwork but why, when we do it in the classroom, do we call it cheating?"

Most of all, it was a nonjudgmental space, where in contrast science and math in traditional educational settings had been soured with embarrassment and uncertainty.

"I just looked at it and said, wow, sports – intentionally or otherwise – has latched onto, and optimized, everything that gets kids passionate," Kamen concluded. "You can strike out or fumble a ball without getting an F or a D. You're nurtured back: "you'll get it tomorrow, we'll practice, you'll improve." I looked at every aspect of it, they bring the school band, and the cheerleaders, and the mascots, and they have a celebration not a test. I said, alright, this is easy."

"Instead of bounce-bounce-bounce-throw, it's mechanical engineering"

"All I gotta do is instead of it being football, or basketball, or soccer, or cricket, or rugby... all I gotta do is do the intensity of the season. It's after-school. At the end of the season it'll be a double-elimination tournament. Use the sports paradigm, but the content – instead of bounce-bounce-bounce-throw – the content is electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, systems engineering, controls, sensors, software. All I gotta do is create an environment literally modeled after what's so attractive about sports, using all the same... even physical locations! And we win! And we did!"

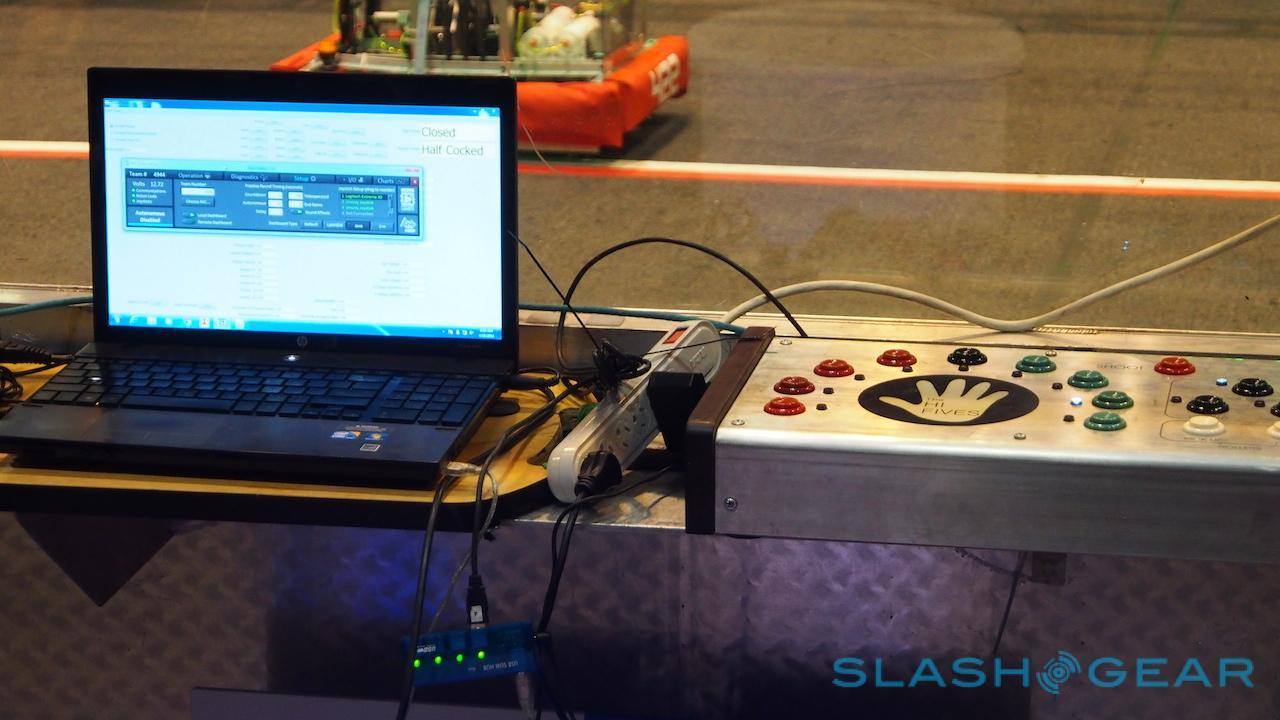

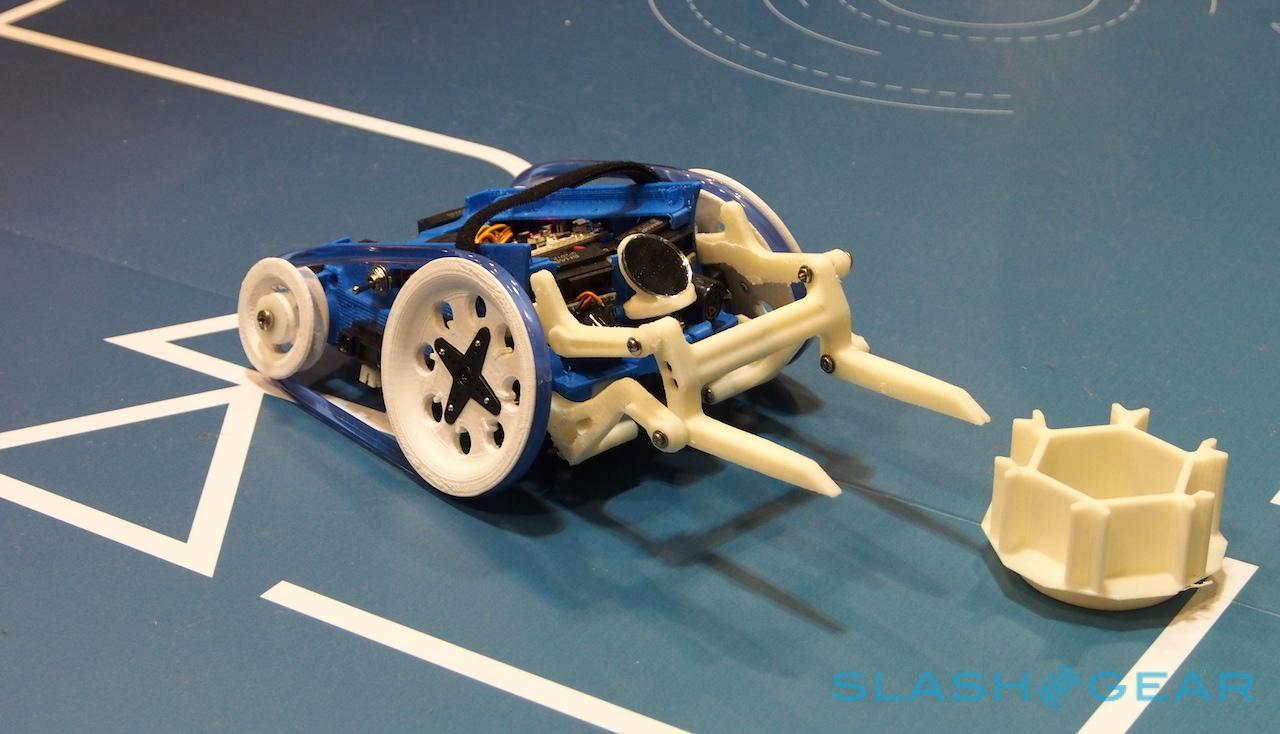

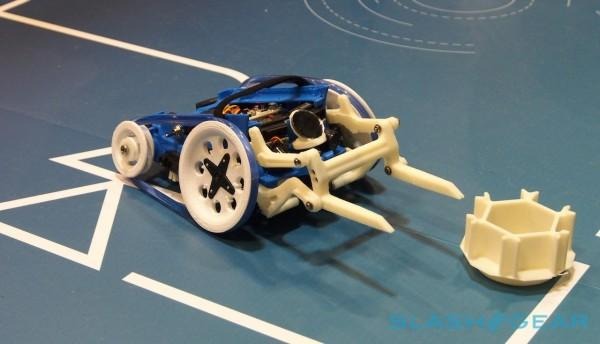

The FIRST Robotics Competition (FRC) is the heart of the program, though the inaugural Championship wasn't held until 1992. Teams of high school students spanning grades 9 through 12 each get a standardized "Kit Of Parts" and the details of that year's challenge; the kit includes the robot's core control system, basic components like motors, structural hardware, wheels, gearboxes, pneumatic actuators, and the software to link it all together.

Six weeks of construction follows, with teams allowed to augment the standard platform with their choice of off-the-shelf extras, as long as each piece doesn't cost more than $400, and the total project budget doesn't exceed $4.000.

Regional and district competitions filter out the best 'bots from more than 2,500 in 2014, with the cream of the crop making it to St. Louis and the three day Championship.

FIRST had humble beginnings – that initial 1992 FRC meet took place in a school gymnasium – but its success over the year proved contagious, motivating younger kids to want to get in on the robo-building action. The FIRST LEGO League (FLL) was started in 1998, challenging Grade 4-8 students to build autonomous robots based on LEGO's MINDSTORMS platform; it spawned the Junior FIRST LEGO League (Jr.FLL) in 2004, with K-3 kids creating models that might help in the event of natural disasters.

Fourth of the quartet is the FIRST Tech Challenge (FTC) for Grade 7-12 students. Most recent of the group – it was created in 2005 – it builds on more affordable kits than the core FRC, coming in at a few hundred dollars rather than the $6,000 it costs a rookie team to get started with the FRC.

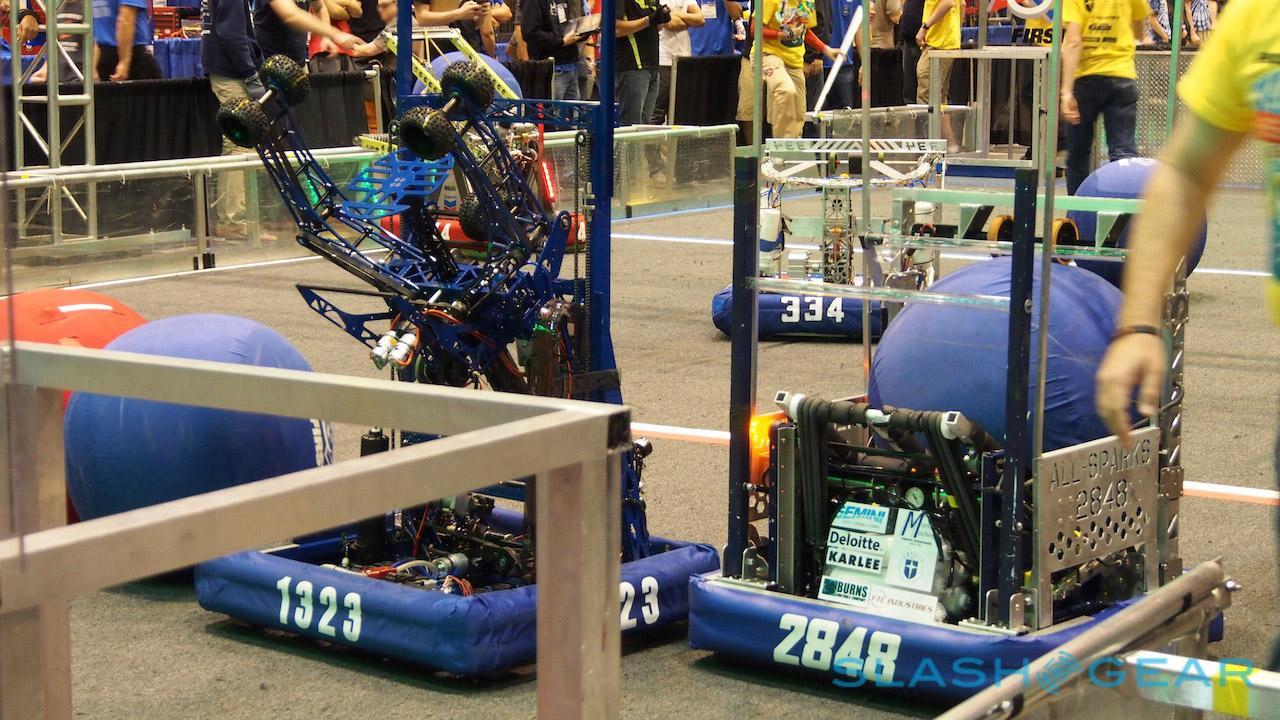

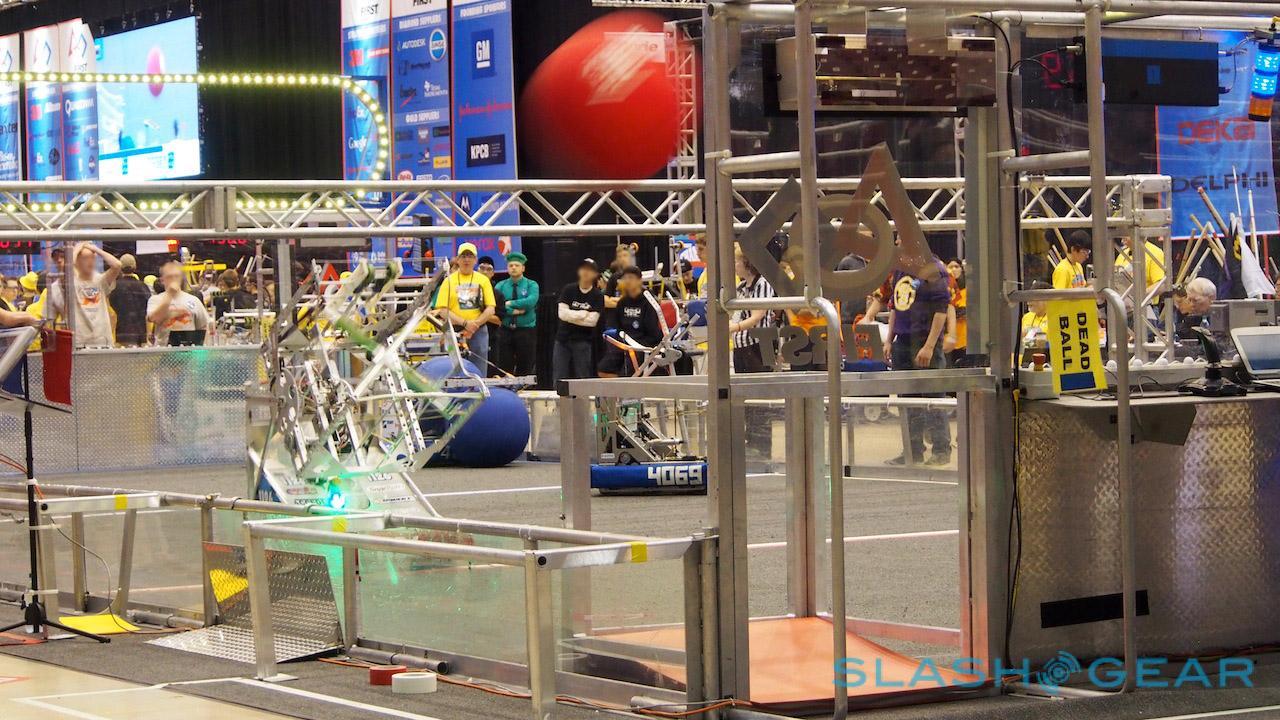

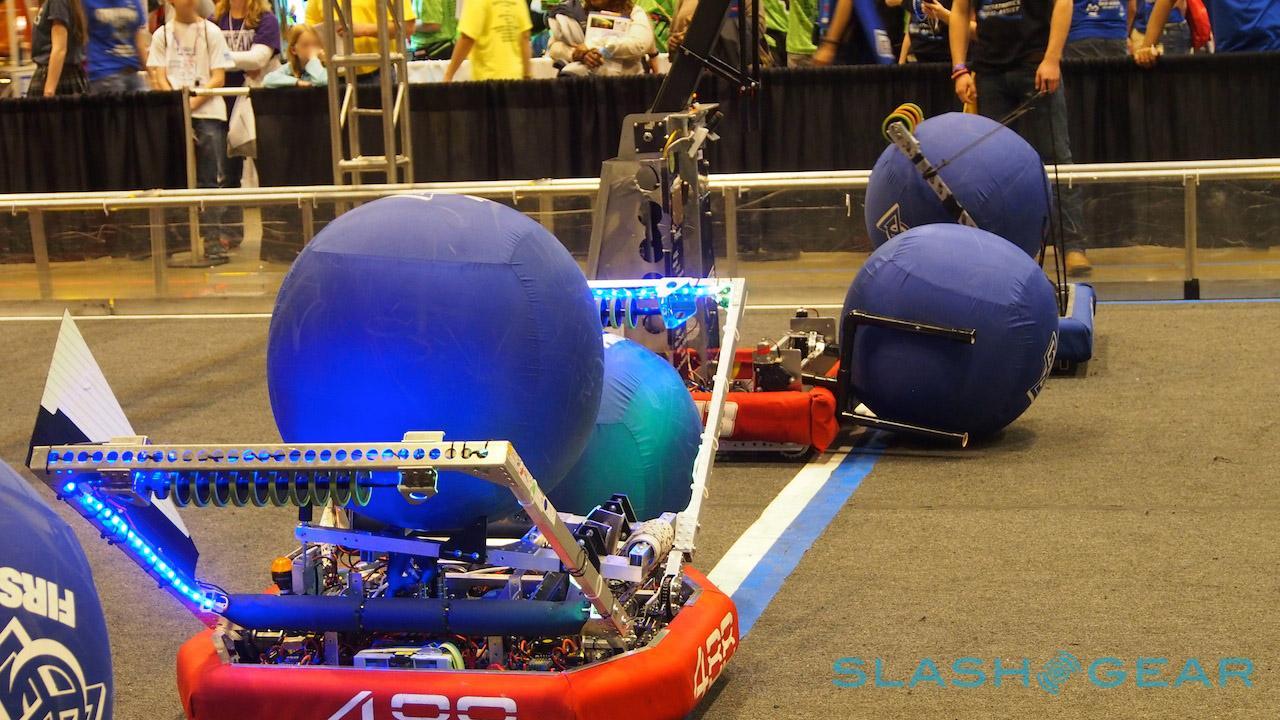

The core challenge facing the students and their robots evolves every season. For 2014, it was a combination of basketball, soccer, netball, and a little wrestling thrown in too. Three teams on each side must work together to throw colored exercise balls either through a broad goal up above the control podium, or into a ground-level box at either side, scoring extra points for firing the balls over the top of a central beam or involving each team's human participant on the sidelines.

It's organized mayhem, and at first I can't make head or tail of what's happening over the course of each brief bout. Teams can, optionally, start out autonomously: carefully lined up facing the goal, and then firing one or two balls according to preset patterns to get an early score on the board. After that, the madness begins.

Six robots scuttle around the field, launching balls through the air with the angry hiss of pressurized air. In the test fields back in the pits there are nets to catch them behind the goal, but out on the main field it's left up to a crew of volunteers to stop them from escaping and then pass them back down to the players.

Within each round, the scope of approaches to the game that the teams opt for becomes clear. Some 'bots use folding metal hoops to reach down and snare the ball; others have huge, petal-like flaps to gather it up. Pneumatics seemed the most common method of then firing it out again – sometimes through a simple cage, though other teams had constructed evil looking claws to hurl the balls – while others had experimented with spinning wheels.

Unusual playing styles spread across players like the flu: effective and increasingly popular this year was chaining together a series of points and bonuses, with robots picking up balls, firing them over the central beam for a bonus and hopefully into the waiting arms of the human team member, who'd then pass it on to another robot for a further bonus, and then from there into the goal itself.

As I watched, teams quick to borrow the strategy racked up points twice as fast as their rivals, who would inevitably cluster together after their defeat to discuss how they, too, could adopt it for the next round.

The intention may be carefully targeting the goal, but that's not to say it isn't a contact sport as well. The playing field has areas where robot-on-robot contact is allowed, and where slamming into your rivals to stop them from lining up their shot, or from collecting their ball, is a key strategy. When they're not catching balls themselves, the human players bounce around frantically on the sidelines, telegraphing instructions or warnings to the pilots. Some had clearly preprepared those gestures; others appeared to be relying on enthusiasm more than anything else.

Enthusiasm is in ample supply throughout, in fact. The core components for each robot may be the same, but just as none of the final designs are identical, neither are the students themselves. Costumes range from matching bright pink suits, through triangular "cheese hats", to enough hair gel and dye to not only give twelve inch red and green mohawks a fighting chance to make it through the day, but probably cause some serious damage to hotel plumbing, too.

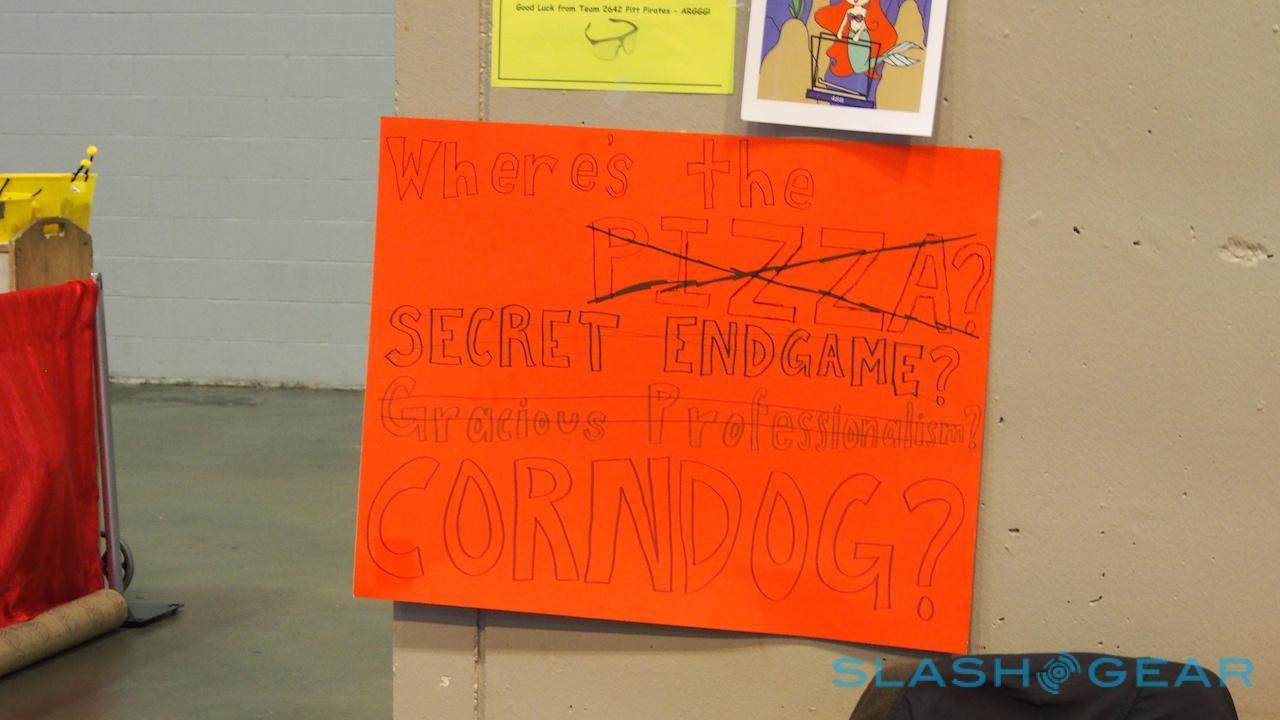

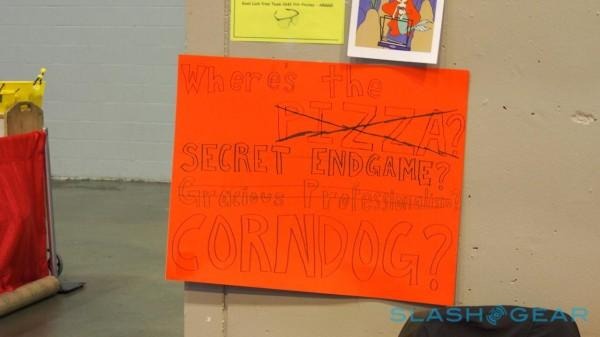

Emotions run similarly high, but FIRST puts particular emphasis on what it calls "Gracious Professionalism": the concept that "fierce competition and mutual gain are not separate notions." It's an important element when you consider that in each match three teams are randomly paired up to work together, having potentially just been fighting against each other in the previous round.

I'll admit, it sounded a little twee to my cynical ears – FIRST even went so far as to register "Gracious Professionalism" as a term – but the kids do a better job at embodying it than I expected.

As I walked around the pits, a shanty town of booths organized into four tournament clusters – named after famous scientists, of course – and each decorated just as riotously and colorfully as the teams themselves, regular announcements over the speakers showed just how much opportunity for empathy and support there is.

"Team 2416 is looking for a USB to ethernet adapter," came one request; "Team 847 is looking for rough-grit sandpaper." Sharing tools, supplies, and expertise is a key part of the FIRST ethos, its pinnacle the 2004 Championship in Atlanta, GA, where four rival teams donated spare parts, tools, and their own hard work to build a new robot for another team whose own hadn't made it to the competition. It took them a day, rather than the usual six weeks.

There's a reassuring absence of hangups around diversity, too. I saw a few all-female teams, and a few all-male, but most were mixed in gender; different ethnicities were represented, and there was a refreshing lack of judgement and prejudice on show. Boys wearing tutus raised no more eyebrows than the anonymous person wandering around in a Stormtrooper suit did; there was no expectation that girls would take the teams' "media" roles while the boys did the engineering.

Still, they're ordinary kids nonetheless. Interspersed with the more commonplace chatter about construction and repairs I heard the occasional tantrum; parents and mentors settling arguments between friends and siblings, or reminding their teams not to overdose on soda and funnel cakes from the stands dotted around the stadium.

That ordinariness is something Kamen bears in mind, too. The FIRST founder may have started out by focusing on building STEM up as an an alternative to the worlds of celebrity and sport, but that doesn't mean he's blind to the doors each can open for him. At the Dean's List awards – the annual prize for the best students – Kamen brought not only deans of admission from MIT and Yale, but musician will.i.am and Seahawks running back Marshawn "Beast Mode" Lynch on stage with him.

"Everyone in this auditorium inspires me," will.i.am told a vocal crowd of students, parents, and mentors. "You guys make tomorrow possible."

will.i.am and Lynch may be the mainstream celebrities, but Kamen is undoubtedly an icon for these kids. While on one side of the stage it's the musician and sportsman being mobbed, on the other it's the FIRST founder being begged for selfies, and asked to sign everything from name badges to shoes.

"Everything about [FIRST] just grew the way every other sport grows. The only difference is our sport is developing the muscle hanging between their ears, and it's the sport in which every one of these kids can turn pro" Dean Kamen, FIRST

Those at the Championship are already converted to the cause, Kamen recognizes however, and so the goal is to hammer down some of the preconceptions about STEM. "We're talking and singing to our own choir," he admitted during the opening keynote. "It took a long time for us to reach out to other industries, and if we don't we're going to fail to reach out to all the other kids that haven't figured out that they want to be geeks."

There's also the tricky matter of paying for it all. FIRST is a registered charity, and while teams pay for their kits, there's a long list of sponsors who are also involved. Kamen isn't afraid of big business, though the points at which altruism and marketing met could sometimes feel strained.

"I've been asked to read... I guess, an advertisement," Kamen drawled during his opening keynote, going on to deliver not a commercial but a reminder of a future FLL meet, complete with a decent name-check for "our friends at LEGO" underwriting a fair chunk of it. The toy company wasn't the only big brand in attendance, however.

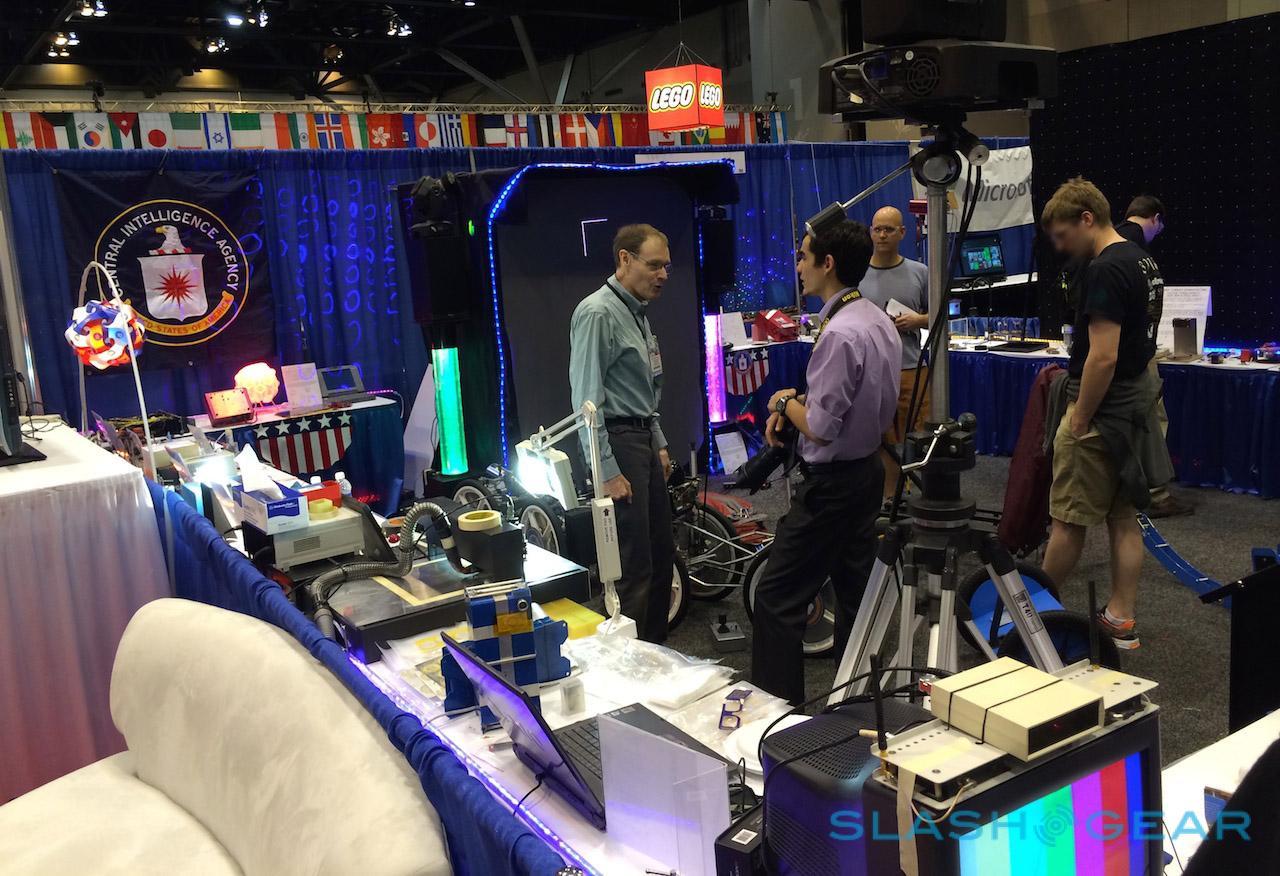

Off to the side of the pits there was a cluster of booths far more familiar for someone who invariably haunts a few tech trade shows each year like I do. Names like Qualcomm – principle sponsor of the Championship – along with NVIDIA and other hardware and silicon manufacturers spared space with some more offbeat attendees: NASA, Boeing, and SpaceX, for instance.

Even the CIA was there, having raided its archives for patented American tech from the ages to display, and sending out a couple of remote-controlled robots in the hope of luring back a few potential candidates for the intelligent agency.

"We're a big fan of STEM, basically, and we want to be part of the community to encourage kids to pursue careers in science and engineering," Matt Grob, executive vice president and CTO of Qualcomm Technologies told me. "It really is true that the world needs it, but it's also true that Qualcomm needs it. We hire a lot of engineers... there's great demand."

Like the CIA and the space agencies, Qualcomm is hoping to at least lodge its name into the memories of some of the FIRST kids. "This is a really efficient, effective venue and channel for funding, we get a lot of return for it," Grob explained. "We also are pursuing the adoption of some of our products into the robots, so the kids will learn to program on our platforms, our Snapdragons, use our modems and things. That way, when they come through school they'll be better prepared to go into the workforce and be very good candidates for us. So it's kind of a virtuous cycle."

That cycle doesn't just mean creating more Snapdragon phone developers; it's also a chance for Qualcomm itself to diversify. "When we approach an organization like FIRST, and say "wow, we'd like to supply you with Snapdragons for your robots", that is an interesting challenge," Grob admitted. "And it's something that has taught Qualcomm that we need to improve how we work with someone who is not a phone manufacturer."

"If you're one of these guys who makes [a smartphone] then we have a nice organization for you, and it all works great. If you want to build robots, or do these kinds of activities... this participation in FIRST has helped Qualcomm to grow. Its allowed us to get new inputs and new applications that aren't necessarily just cellphones. It's also, for some sense for us, a chance to look forward. Robotics is growing. Things like automated vehicles, cars, those are essentially robots, or becoming more robotic. So our participation here also gives us a look forward" Matt Grob, CTO, Qualcomm

Qualcomm had brought along its DragonBoard, a development kit using the same Snapdragon 800 processor and Adreno 330 graphics that you'd find in recent high-end smartphones, but exposing connections and ports for more impromptu tinkering.

It's already been the heart of an impromptu upper-atmosphere photography rig, sent up in a polystyrene crate under a balloon to snap images and then parachute back to Earth, but in the next 4-5 months it'll get an optional robotics shield too, senior director of business development Tia Cassett explained to us. Together, Qualcomm hopes they're going to be a perfect sub-$200 platform for robotics projects, including support for things like object- and face-recognition out of the box using Vuforia.

"What you see around here is experimentation," Grob concluded. "One of the things FIRST has taught us is how to make our platforms more suitable for experimenters. In the past, it was really hard. You had to be a giant phone company, and you couldn't just get a board to do your project on from us."

"But because of experiences like FIRST, and all these teams, they don't have huge budgets and five years of time, they need to get a board and they need to have it be open and easy with documentation. Community for support. We've come a long way in those areas because of our participation with FIRST."

I expected the corporate booths to be a dead zone, but the interest the kids showed surprised me. Admittedly they were probably most keen on NVIDIA's stand – the company had brought along a triple-display gaming rig, and there was a long line of eager players – but that's not to say they weren't intrigued by the scope of the chip, software, and 3D printing specialists that were represented. "They ask far harder questions than most adult developers I speak to at shows," one company rep admitted to me.

That curiosity might be because the potential to use FIRST as a stepping stone into a career is well known among the high school kids involved.

Kiet Chau, who is now a mentor for San Diego FRC team Holy Cows, is probably a poster-child for that possibility. He got his start at Qualcomm – where he's currently an engineer in the company's Labs R&D division – having been spotted at a FIRST event in 2008 and invited to apply for an internship.

When I spoke to Chau, on his way back with the Holy Cows from their final qualifying match, things hadn't gone entirely to plan. A day of mixed games meant the team wasn't going to automatically go forward to the finals, and would instead have to count on having been spotted as a potentially valuable alliance member and be invited to take part.

In the end, though, the winning alliance on Saturday night consisted of The Cheesy Poofs from San Jose, Calif.; Las Guerrillas from Bloomfield Hills, Mich.; The All Sparks, of Dallas, Texas; and Team C.H.A.O.S., from Holland, Mich. The Holy Cows didn't go home empty-handed, mind, taking away the Media & Technology Innovation Award instead.

Gracious Professionalism aside, it's perhaps telling that FIRST falls short of naming a single team the overall winners, prizing the quartet that collaborated most impressively instead. While the enthusiasm and pure smarts of every kid I spoke to were clearly evident, so was the message – from Kamen down to every mentor and volunteer – that although intelligence may give you an opportunity, it still takes hard work to actually achieve anything.

Kamen has high hopes for what his robotics competition can still achieve, not only in the US but all across the globe. "These kids, this year, they are going to help us organize an alumni that will make FIRST a dominant cultural interface around the world," he insisted to me, relying on science as a universal language.

"Everything else in the world is different: your food is different, and your housing is different, and your culture is different, and your religion is different. But the last time I checked, F=MA, works pretty much everywhere. E=IR? Yeah, voltage and current and torque and speed. Last time I checked, trigonometry in any language, sin(theta) is sin(theta)."

It's also a chance to push back some at things like sports and entertainment that, while broadly celebrated, don't necessarily pay the bills. "This is the only sport where every kid on every team can turn pro." Kamen promised to me, before downplaying his own role in the creation of the robotics challenge.

"I think most people think inventors start from scratch, in everything they do, with a clean piece of paper. And most good inventions I've worked on or seen are at the intersection: "oh, they've finally made batteries high density enough you can make an electric car"; "oh, they've finally made processors so power-efficient and low-cost you can make, not a cellphone, but a wearable PC.""

"Great inventions are the intersection of technology advances that meet needs in ways that weren't possible before, but you then extrapolate them. And FIRST proved a success, even in the ways I've never fully thought about, though I'll be happy to take credit for 'em if history writes it that way."

Thanks to Qualcomm for hosting me at the FIRST Championship.