Regin malware: three things you need to know

Today the folks at Symantec have reported their discovery of the malware known as Regin. This software is detected by Symantec and Norton products as "Backdoor.Regin", and it seems clear that given the complexity of the hack, a nation state is likely responsible for its creation. This software is extremely "low key", meaning it can remain undetected for several years in a system, and even if it IS detected, it's not always possible to find out what its been up to.

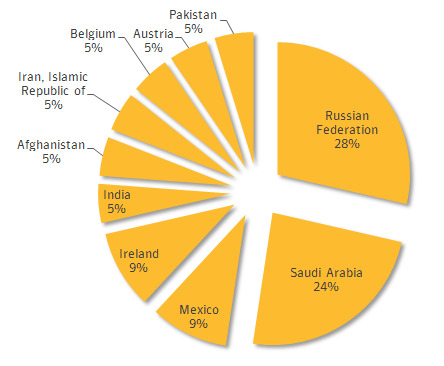

1. Infections have appeared mostly in Saudi Arabia and Russia

A whopping 52% of infections with this Regin tool have appeared in the Russian Federation or Saudi Arabia. According to Symantec, the United States does not even register as a percentage point in their chart of the top 10 countries in which they've found victims.

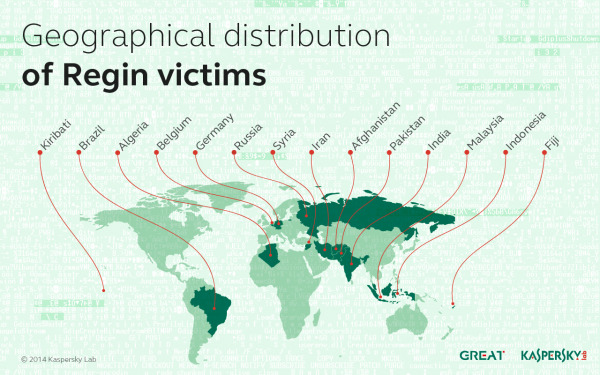

Kaspersky also has a chart for where they've discovered victims of the Regin malware. The map you see here shows both countries where Regin was discovered active and where it was found cleaned, but where it left traces of itself nonetheless.

2. Regin's "stealth" features

What can Regin do if – by some astronomically unsound chance – you're infected? It can do lots of fun things in your computer, including, but not limited to:

• Capturing screenshots

• Taking control of your mouse's point-and-click functions

• Capturing and transmitting passwords

• Recovering deleted files

• Monitoring network traffic

Symantec suggests that Regin works with a modular structure, meaning it's relatively straightforward in its ability to plug-and-play different features for different machines. A malicious entity could create a version of this Regin malware to fit your computer specifically, lifting what it desires through its own unique means of attack.

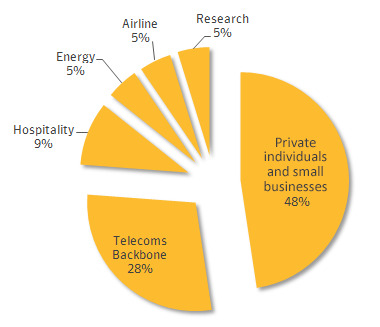

3. Targets

Fist and foremost – you are almost certainly not a target. Regin does not appear to be a broad, far-reaching entity aimed at collecting the names and passwords of the public. It's aimed instead at unique, private individuals, small businesses, and telecoms backbone.

The chart above comes from Symantec and shows confirmed targets between 2008 and 2011 as well 2013 forward. The first segment of time ended in 2011 when Regin appeared to be "abruptly withdrawn" – it then resurfaced in machines in 2013.

Above you'll see how nearly half of infections targeted small businesses and individuals, while attacks on telecoms companies "appear to be designed to gain access to calls being routed through their infrastructure."

Again, this mostly appears to be centered in Saudi Arabia and Russia – but you never know, it could spread. Symantec and Kaspersky have been tracking this system for years and it's only now become worthy of a report. Expect Regin to pop up again, but don't get TOO worried.