Philae future in question as comet lander battery dwindles

The Philae lander that traveled 3.98 million miles to land on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenkohas is now frantically attempting as much scientific research as it can, with the ESA concerned that its batteries could die in less than a day. The European Space Agency planned to run Philae, its Rosetta mission probe to a comet hurtling 80,000 mph through space, through until March 2015, investigating how the icy space rock was affected by the sun as it travels in the solar system, but an awkward landing – or, more accurately, three landings – has left the future of the experiment in question.

Philae's landing on Comet 67P was never going to be straightforward. The ESA was relying on the rock's small amount of gravity to slowly bring the lander down over the course of around seven hours, but since that tiny pull wouldn't be enough to pin it in place once drilling began, some way of holding it in place was required.

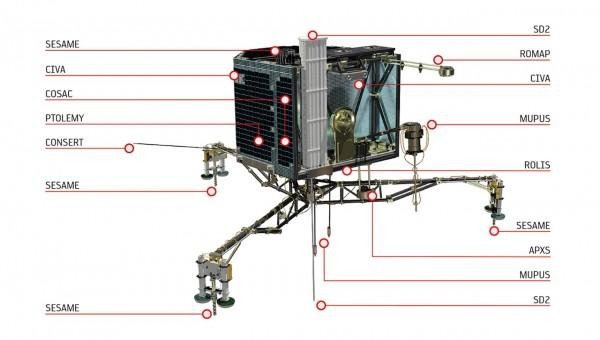

The answer included a harpoon system, intended to spear Comet 67P and winch Philae in, as well as a trio of drill-equipped feet to burrow into the surface rock. Finally, an upward-facing rocket could be used in a pinch to effectively force the lander's feet into place.

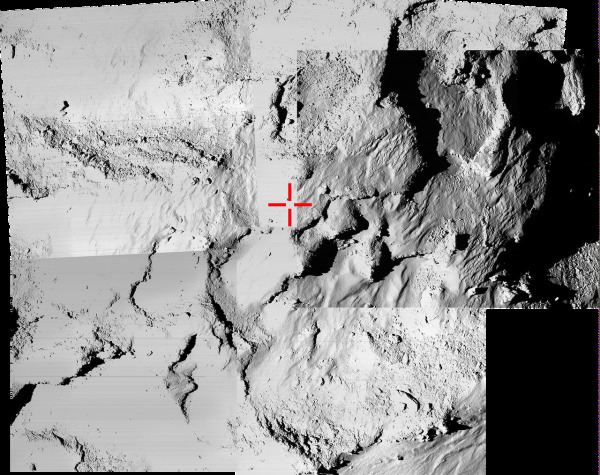

Great in theory, but in practice things didn't go to plan. Reviewing the latest landing data shuttled back via Rosetta's long-range radio system, the ESA discovered that Philae in fact had three separate landings, following the failure of the harpoon system to do its job.

The first touchdown was within the area the ESA had initially earmarked, but it then effectively bounced up and traveled approximately 1km (0.6 miles) at 38 cm/s over the course of almost two hours. A second, final bounce for seven minutes took it a little further.

Philae's problem is that, while the original landing site would have given its solar panels light for more than half of the comet's 12.4 hour long day, its current position gets only 1.5 hours of sunlight each day.

The primary battery, which is used to power the "core science goals" according to the ESA, is set to run out in the next 24 hours, while the secondary batteries – charged using the solar system – are going to be woefully underpowered in the lander's current position.

Adding to the confusion, not only is Philae's location unclear, but it's still not properly anchored to the comet.

That left the ESA scientists with the difficult question of whether to deploy instruments which could in the process shift Philae even further. In the end, MUPUS – which uses a small hammer – has been switched on, and could help bounce the lander into a more useful position, while the APXS (Alpha Proton X-ray Spectrometer) is working at better understanding the composition of the rocks around it.

If the ESA can effectively jump the lander into a spot with sunshine, or even just rotate the solar panels into a more efficient position, that could stop Philae's premature demise. More complex approaches could include using the harpoon system or thrusters to hop elsewhere.

It will need to work fast, though, as there's limited power remaining to transmit between Philae and Rosetta.

SOURCE ESA