Google, all major payment companies shun pay-to-remove mug shot sites

Google is demoting commercial mug shot websites in search results, the New York Times reports, and MasterCard, PayPal, American Express, Discover and Visa have all stated they are in the process of terminating payment services to the owners of such sites. This mass revolt started when influential reporter David Segal called the search engine and the payment companies with a few simple questions last week. Their spectacularly unified response could drive the 80-plus pay-to-remove mug shot publishing operations into relative obscurity—much to the relief of the millions of people who have ever been arrested but not convicted of any crime.

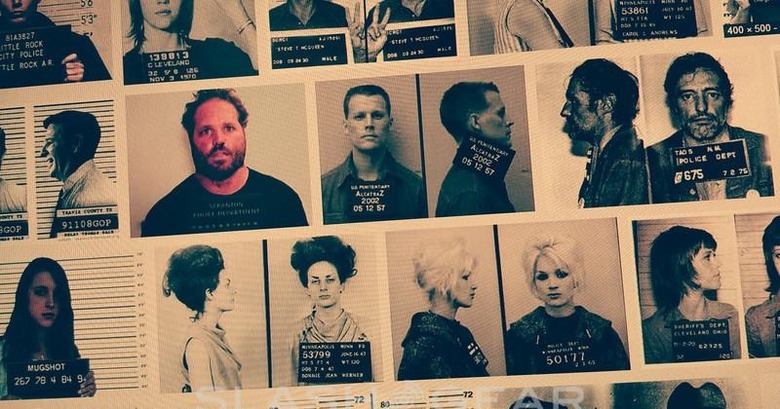

Mug shots have long been a matter of public record, and anyone can access them online through the websites of local public records offices, but their commercial counterparts differ in three glaring respects. One, you can't pay $30, $100, $400 or in some cases $899 to a public records office to take down your arrest glamour shot, whereas with the commercial sites you can do so quickly and easily with a credit card. Two, some of the commercial sites are intentionally sensationalist: your mug shot could appear in context with the likes of accused national traitors, Lindsay Lohan and the Aurora, CO murderer (see screenshot above.)

And three, commercial mug shot sites have, since their rise to prominence in 2010, tended to rank high in Google search results. This is because the sites as a group are intentionally packaged to encourage idle browsing, thus keeping eyeballs glued to their pages for longer periods. Google's algorithm rewards slow bounce rates with high rankings. Anyone who has ever been arrested is therefore likely to see their mug shots appear on the first page of Google results for their name. Everyone else can see those mugs too, including prospective employers, clients, neighbors, acquaintances, blind dates, and millions of strangers who enjoy seeing other people humiliated.

A Google spokesperson initially told reporter David Segal there was nothing Google could do about the problem, because the ranking rules are the rules and can't be lightly bent or broken. But another Google rule penalizes sites that glean content from other sites rather than produce their own unique content. Gleaning images from public records is the only way commercial mug shot sites find content. That could well be the rule under which Google demoted the sites: the spokesman got back to Segal a few days later and said he had since learned that the company had been working on the issue for months. Whatever the case, arrestees' mug shots started disappearing from the first page of full-name search results mere days after Segal contacted them.

The payment companies, having been directly asked by Segal what they were doing to stop abetting the sites' search engine optimized extortion operations, started severing ties with the sites the same week.

"We looked at the activity," one MasterCard lawyer said, "and found it repugnant."

As clear-cut as the issue may be to some observers, certain public safety champions (such as mug shot site proprietors) have vocally resisted legislation curbing the sites, defending them as a vital public service in a world full of perverts and parking ticket snubbers. Free speech purists have argued that such measures would amount to "an effort to deny history." Most states therefore have been reluctant to move on the matter.

Meanwhile, anyone can selectively access the exact same mug shots through publicly owned websites that no one can pay to be removed from.

SOURCE: New York Times