Android phones may not be as secure as they claim

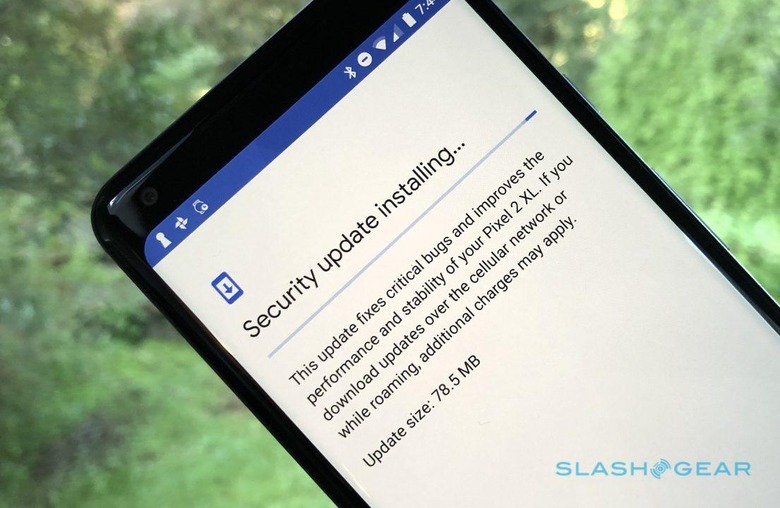

Your Android phone may not be on the level when it tells you it's up to date on software, with security researchers warning that even device-makers releasing relatively timely updates could in fact be missing out security updates. Over the past few years, Google has pushed its OEM partners like smartphone manufacturers to be more aggressive with their updates, but it's been an uphill battle.

Indeed, not for nothing does Android have a reputation for being a Wild West of security patches and OS versions. It's not just cheap phones and tablets that are still being sold running a version of Android several generations behind the cutting edge, either. Top tier phone-makers have also demonstrated that they're not on the ball when it comes to releasing new software versions, with delays stretching to months after Google makes the core software available.

Now, Wired reports, a team from Security Research Labs plans to reveal a lapse that's arguably even more concerning. In a presentation at the Hack in the Box security conference, Karsten Nohl and Jakob Lell will detail the results of two years of reverse-engineering Android device code. The pair looked at 1,200 Android phones, they say, to see if the security updates that had been made available were actually included.

Worryingly, in some cases, they were not. Nohl and Lell have dubbed it the "patch gap": a discrepancy between the patches available and what's actually been included. "It's small for some devices and pretty significant for others," Nohl says. As many as a dozen patches could be absent, the research found.

Even when updates were available, they might not be what they seem. "Sometimes these guys just change the date without installing any patches," Nohl says. It looked at more than a dozen phone manufacturers, including Google, Samsung, HTC, Motorola, and ZTE.

Google, for its part, counters that there's more to the issue than just misleading manufacturers. While it agrees that the area needs greater attention, it also points out that some of the devices in the study may not have been Android certified, meaning the standards of security they're held to are different. It also highlighted Android's core security features, which have made hacking even unpatched phones more difficult, and counters that some of the missing patches may have been down to companies leaving out the features they relate to.

Nohl says that last point is actually very uncommon, but welcomes more attention to the issue. There are a number of possible contributing factors, the research suggests, beyond just vendor. While some manufacturers only missed at most one patch that SRL was looking for – including Google, Sony, Samsung, and Wiko – other devices, particularly those using MediaTek processors, had far more absences.

Actually taking advantage of unpatched phones is still a tricky matter, and the security risk is almost certainly still higher from simply downloading a compromised app. Nonetheless, it's another sight of the challenge Google faces in trying to elevate Android's security credibility, particularly when it comes to a matter it can only hope to influence, not control.