The Origins Of The QWERTY Keyboard Explained

"Fingers on the home row!" Those words were drilled into us every single day in basic keyboarding class in high school. What is the "home row," you may wonder? Well, knowing the "home row" is the difference between the two-finger "pecking" system and the auditory poetry of the 80+ words per minute "clickity-clack" of skilled typists.

Given how important the written word is for our modern way of life, the keyboard really should be mentioned right after the wheel as one of the most important inventions in the history of this little planet. With a keyboard at the ready and some proper typing skills, the sky's the limit. From responding to important e-mails, staying in touch with friends near and far through various communication services, to writing groundbreaking novels, our world would look very different without the keyboard. This important device can have up to 101 keys on it and continues to change people's lives everywhere. It seems so simple, yet is more complex than first impressions would indicate.

The home row

To people just starting out, getting away from the two-finger pecking system, the rhythmic flow of fast-typing fingers might seem like magic, but the simple secret is really in the "home row."

On a basic QWERTY keyboard, putting your left-hand fingers on the middle row of your keyboard, specifically the A S D F, and your right-hand fingers on the JKL and ;(Semicolon) keys respectively, allows you to access just about every key on the keyboard with just a small, little, effortless movement either up, down, or directly or diagonally across (via NIDirect). This is called the "home row."

Just like on a musical keyboard, your fingers lie slightly curved on the middle keys, ready to quickly exert downward pressure and allowing you to reach the surrounding keys with ease, without really having to lift up your fingers from that position, NIDirect notes. Everything in typing starts with that hand position.

With enough muscle memory and practice, you just know instinctually where the corresponding keys are under your fingers, allowing you to type almost as quickly as you can think those words in your mind.

Why are the keys not arranged alphabetically?

When you see a standard keyboard, you might wonder why the keys are not arranged alphabetically. Truth is, this would actually make typing much, much slower (via Sage Journals). So the QWERTY layout, which is still standard today on English keyboards, came along. This simple, but genius layout design was devised and created all the way back in the 1870s by Christopher Latham Sholes, a newspaper editor and printer, who lived in what is now Kenosha, Wisconsin. Is there any specific logic behind it?

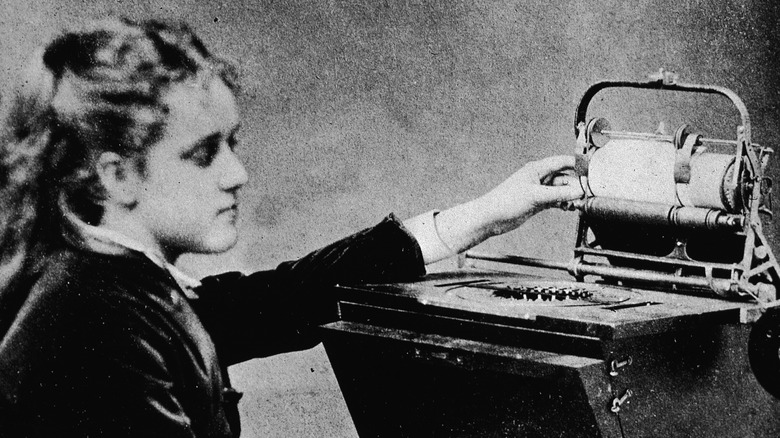

The origin of this particular layout lies in ancient typewriters — specifically the forerunners of the Sholes & Glidden Type-Writers, which were conceptualized by the aforementioned Christopher Latham Sholes, and his business partners Samuel W. Soule, and amateur mechanic Carlos S. Glidden. The idea for these devices came out of necessity since the typed word was becoming more ubiquitous in daily life. These machines were developed for more efficiency in daily business (via Smithsonian). The very first versions and prototypes actually had an alphabetical layout of keys, however.

The specific reasons why the keyboard was changed to QWERTY then remain a bit foggy, resulting in two competing, or perhaps complementing stories of what happened next.

Theory 1: Mechanical troubles led to the QWERTY layout

It was previously thought that Christopher Latham Sholes and his business partners Samuel W. Soulé and Carlos Glidden, along with American inventor and businessman James Densmore, ran into some mechanical troubles with their prototype devices (via SciHi). In the previous alphabetical arrangement, common letter pairings would jam the bars inside easily if typed too quickly, the inventors noted. This problem led these gentlemen to the idea to rearrange the keys in order to slow typists down and thus avoid jamming the machine. The theory goes that QWERTY was chosen more or less based on a combination of often-typed letters and words and by incorporating several requested changes from telegraphers who had to transcribe morse code quickly, Mental Floss notes.

This version, however, was somewhat debunked by researchers Koichi Yasuoka and Motoko Yasuoka from Kyoto University in a 2011 paper. The pair essentially concluded that the mechanics of the typewriter did not influence the design and therefore layout of the keys, nor was Scholes trying to slow down the potential users of these devices. Rather, it was found that early testers — mainly those same telegraph operators who found the alphabetical arrangement too confusing — were responsible for the layout changes.

Theory 2: A clever business decision led to the QWERTY layout

The other popular theory is that after Samuel W. Soulé left the initial enterprise and was replaced by James Densmore, it was a business decision to basically lock typists into a specific system in order to ensure their brand loyalty to the typing machines manufactured by gun maker Remington.

Remington was approached for its experience with precision manufacturing, and eventually acquired the rights for manufacturing these machines in early 1873 in order to branch out of the arms business. They had the very clever idea of ensuring that companies who hire typists would need to also purchase these Remington typewriters and training courses for them (via Smithsonian Magazine). It's kind of similar to certain electronics manufacturers like Apple, who lock you into their walled garden, so to speak.

Which theory is ultimately right? We may never know, but just like with anything in life, the truth probably lies somewhere in the middle. An interesting tidbit here is that Sholes himself wasn't entirely convinced of the efficacy of the QWERTY setup. Although he eventually sold his designs to Remington and became quite wealthy, he continued experimenting with different layouts and designs for the rest of his life (via Smithsonian).

Looking at the competition

QWERTY is so ubiquitous now that not many people are even aware that it isn't the only viable keyboard layout. Dr. August Dvorak developed another popular layout — the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard – in the 1930s. This layout places the most commonly used letters in the home row, where they're easy to reach, and the least commonly used letters on the bottom row, where they're the hardest to reach. While QWERTY results in most typing being performed with the left hand, Dvorak results in most letters being performed with the right hand (via DIfference Between).

Compared to QWERTY, users of the Dvorak layout have claimed faster and more accurate typing because the number of words which can be typed using the "home row" is dramatically larger. This claim was debunked by recent research, however. Dvorak is not proven to be faster –- the highest recorded speed on QWERTY is 227 words per minute, while the highest on Dvorak is 194 WPM. However, one extraneous variable here is that there are many more people who have practiced QWERTY for their whole lives than there are people who have used Dvorak. Perhaps, if more people used the Dvorak layout, there would also be a fastest Dvorak typist.

Some do prefer Dvorak for typing comfort, rather than speed, as How To Geek points out. When typing with Dvorak, your fingers move only 62% as much as they do with QWERTY, so it's less strain on your finger muscles.

Can QWERTY hold up in the modern world of smartphones and tablets?

The advent of smartphones and tablets have changed our typing habits significantly — yet these devices still employ the QWERTY layout. Many modern, everyday devices don't require a physical keyboard anymore (via Stack Exchange).

Many User Interface Designers are convinced that as computing becomes more mobile, touchable, and especially wearable, and as augmented and virtual reality become more commonplace, we will need new and more efficient ways to input words into our modern communication machines. Michael Eichenseer deep dives on the topic for MIT Technological Review, via Medium.

There are currently several updated input methods we already rely on more and more. Voice recognition is becoming ever more popular with each passing generation of devices.

"Hey 'SiGooLexa', do you know what the home row is?"

Just like words on traditional keyboards, there is a certain learning and adjustment period when it comes to remembering how to correctly dictate proper punctuation marks into your writings. With some practice, however, this is a relatively fast and efficient way to quickly input a note or answer an email.

Is QWERTY here to stay?

Another potential threat to QWERTY is predictive text. No, Siri, we're not trying to say "ducking." How many times have you wanted to say something in a message, but it was automatically corrected to something totally different?

Though certainly useful and convenient, is predictive text a better input method than just typing each word out? For one thing, no one will look at you weird on a crowded train or bus when you send messages to your friends, family, co-workers, or even your editor. However, we all know the frustrations predictive text can cause. There are plenty of articles dedicated to the oftentimes hilarious results when the wrong word or even phrase is suggested.

Because let's be honest — predictive text was never designed for when you want to sit down at your desk, ready to get some compendiously articulate adoxography done.

Over the years there have been numerous attempts at making a new input method palpable for the mainstream (via MIT Technology Review). We're sure some brilliant scientist is on the verge of completely changing our way to communicate and get our thoughts out on the page. Until then, however, QWERTY is not going anywhere, so get your fingers on the home row.

In turn, this might well explain why Christopher Latham Sholes and James Densmore didn't bother to leave behind a definitive explanation of the way in which they settled on QWERTY — just to keep a little mystery left in this world.