Next-Gen Farming: How Satellites Could Help Fix The World's Nutrient Crisis From Space

In the near future, satellites could be used to monitor the level of nutrients in food crops in their early growing days, allowing farmers an early insight into issues that can be fixed and potentially easing the issue of global malnutrition. The deficiency of micronutrients in the food one eats despite consuming enough calories — a trend also known as hidden hunger — is one of the biggest food insecurity problems, affecting over a billion across the world.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations also highlights "unacceptably slow progress in reducing hunger and malnutrition" in its detailed report. The core issue here is that merely feeding is not enough, as the focus should be on providing a diet that is rich in essential micronutrients. But there are challenges from multiple perspectives. Getting harvest grains analyzed in the laboratory for nutrients is expensive and time-consuming, but an even bigger problem is that the measurements can only happen after a harvest.

There is no way to assess the nutrient composition of a growing crop in its early days of growth. If that knowledge were available, interventions such as supplying the right chemicals could fix the nutrient gap. That's where a satellite could come into the picture by analyzing a growing crop's core nutrient composition and offering farmers an opportunity to fix the gap. Early research conducted by experts at the University of Twente and the National Research Council of Italy has already yielded encouraging results.

How it was made possible

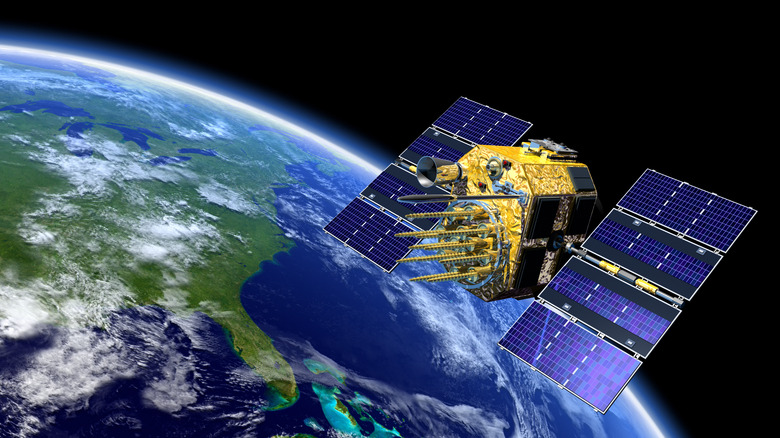

Satellites are home to different kinds of sensors, but not many can reliably read the chemical composition of crops. But there's a class of tools — specifically the hyperspectral instrument installed on the Prisma 2 mission managed by the Italian Space Agency, and the multi-spectral system fitted on the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission — that can do the job. For the latest research, which has been published in the Remote Sensing of Environment Journal, a team of scientists relied on these sensor readings to analyze corn, rice, soybean, and wheat fields in Italy's Po Valley region.

The team picked a small batch of important crop minerals that were identified in the spectrum analysis by the satellite-mounted sensors and then compared them to the results they obtained from lab analysis of the grains. The satellite analysis was done at three core stages of the crop cycle — vegetative, reproductive, and maturity — in 2020. This unique approach to predicting the macronutrient and micronutrient content of a growing food crop yielded positive results for important elements such as potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, and iron.

The accuracy of nutrient prediction in growing food crop fields using satellite data was found to be promising in the case of wheat and soybean. However, when it came to analyzing minerals like calcium and nitrogen across four of the target crops mentioned above, the accuracy was not particularly high, especially in the cases of corn and rice.

A promising future

For the research, the team got positive results from the readings collected via PRISMA in the shortwave infrared (SWIR) band and the Sentinel 2's near-infrared (NIR) band. Limitations aside, the findings from the HyNutri project were encouraging enough that the team is already sketching up plans for a follow-up project called EO4Nutri that will assess maize, rice, sorghum, teff, and wheat crops for a total of nine nutrient targets: calcium, iron, magnesium, nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, selenium, sulfur, and zinc.

The project is backed by the European Space Agency, and will rely on the agency's CHIME satellite mission that will carry an advanced hyperspectral instrument for assessing a bigger diversity of crop nutrients. "We hope this research will eventually lead to farmers being able to intervene and boost the nutrient quality of grains early in the growing season," says Espen Volden, Coordinator of the Earth Observation Science, Applications and Future Technologies Department at the ESA.

The final objective here is that satellites will provide an early warning pipeline to farmers and government-backed food agencies if a growing crop field is lacking crucial nutrients in the early days. Accordingly, farmers and the agricultural stakeholders will be able to fix the deficiency issues with measures like supplying the soil with the necessary organic or inorganic supplements to ensure uptake by the plants. The approach holds a lot of promise in times when climate change has hurt famers across the world.